Jobs to be done personas

Focus on the job, and all else will follow.

There are so many different types of personas, it can sometimes make your head spin. And, oftentimes, people don’t generally like any of them. When describing personas, people use “useless,” “confusing,” “stupid,” and many other negative words. I have had people tell me to use them and others who tell me to avoid them…and, like most, people who throw their hands in the air, unsure of what to do.

Regardless, I have a soft spot for personas. I truly believe, with the right lens and mindset, they are a great tool to be used for innovation and decision-making. Personas are fictional characters that embody the typical characteristics of different user groups. See here: they are a fictional embodiment. We have forgotten that personas are a tool to be used, not the answer to all of our questions, or the solution to all of our problems.

How I use Personas

The reason I create personas is to help my teammates understand the story and the relevant context of our users. I’m not just trying to shove as much information as possible on to an A4 poster. I want to help my team make decisions with the information I give them. I believe, if we are mindful of how we use them, they can be excellent tools that can help guide teams towards better decision-making and innovation

What are the benefits?

- Set the focus

- Empower product and design to make better decisions

- Builds empathy for the users and promotes a user-centered mindset

- Make our assumptions explicit

- Keeps users at the center

- Show the realistic

- Helps to inform user stories

- Aligning the organization on the same language

Now on to Jobs To Be Done Personas…

First off, let’s start off with a small explanation of Jobs To Be Done:

Jobs To Be Done encompasses the concept that users are trying to get something done, and that they “hire” certain products or services in order to make progress towards accomplishing goals. Usually, we all want to be better than we are in a given moment. We all have goals that lead us closer to our ideal self. So, we will look for, and purchase, certain products or services when our current reality does not match what we want for the future.

With Jobs To Be Done, we are completely solution-agnostic. We aren’t even thinking about our product or any products in general. We are focused solely on people’s motivations and how they act. We try to identify their anxieties and the deeper reasons of why they act the way they do, and why they respond in certain ways.

For instance, if we have a travel product that allows people to buy all types of travel tickets online (bus, car, plane, scooter, you name it), we focus our research on how people are using this website/app and how they buy tickets online. However, when you think about it, people didn’t buy tickets online in the past, so this kind of platform didn’t exist back then. And in ten years, there will probably be a new way to buy tickets we don’t even know about yet.

The point is, people still need to travel for various reasons. That job remained stable throughout the years, and the solutions created for it have changed. People will use different products that allow them to get their job done in a faster, better way.

So, if you are just focused on the best ticket buying experience, you will be relevant for some time, but, eventually, competitors will overtake you. Instead, we need to focus on the job people are trying to accomplish: getting from one place to another in the fastest and easiest way possible.

If you look up Jobs To Be Done Personas, you will often find articles called: “jobs to be done versus personas.” When you put these two concepts together, it is usually an either/or conversation. They don’t seem to be able to exist together, in harmony. Most people believe you either do JTBD research or you have personas. I, however, disagree. I believe there is space for a JTBD persona.

How to Create JTBD Personas

Creating JTBD personas is fairly similar to the process of creating other personas. There is a lot of research, analysis, and synthesis. Below is how I created our first JTBD personas.

- Do JTBD research. The first, and most important step, in creating these personas is to do the foundational research. I interviewed around 20 people in this style of interviewing before I started to come up with the concrete personas. Some people say you can make them with less, some only with more. Either way, it is whenever you feel comfortable enough with the data you have gathered. Keep in mind, these will keep changing, so nothing is set in stone. If you have never done JTBD research, feel free to read my guide: https://dscout.com/people-nerds/the-jobs-to-be-done-interviewing-style-understanding-who-users-are-trying-to-become

- Define the goal of the persona. What is it that you are trying to accomplish with your persona? There are several different goals you can have when creating a persona. Below are the various reasons I have created them:

- Show colleagues who our customers are

- Highlight the behaviors of user groups

- Present high-level motivations of users to highlight the why behind certain behaviors

- Tell a story of a user’s life and how they operate when they want to accomplish a certain task

3. Decide on the information to include. I always do this before synthesis so I know what I am looking for when I comb through the data. JTBD personas include slightly different information than what I would put in more “traditional” personas.

- Motivations. I believe motivations are the most important part of the JTBD interviews, and the most important information to include in the personas. JTBD highlights the motivations behind our actions. I separate motivations into three different categories: ideal self, experiential self, and social self.

Ideal self motivations: What is getting the person closer to their ideal self? What are they doing to get there?

Experiential self: What is that person trying to experience in order to get closer to the ideal self? How do they want their environment to impact you?

Social self motivations: How is the person trying to be seen by others? How do they want their relationships to function and get them closer to the ideal self?

- Values. What does the person, at a high-level, value in day-to-day life? What are the concepts or ideas that are important to them?

- Needs. What does the person need on a day-to-day basis? What is important for them to have to accomplish their goals?

- Pain points. What is a painful experience for that individual? What do they try to avoid? What causes them anxieties?

- Goal (or job). What is the goal (or job) they are trying to accomplish? What is the outcome they would like to achieve?

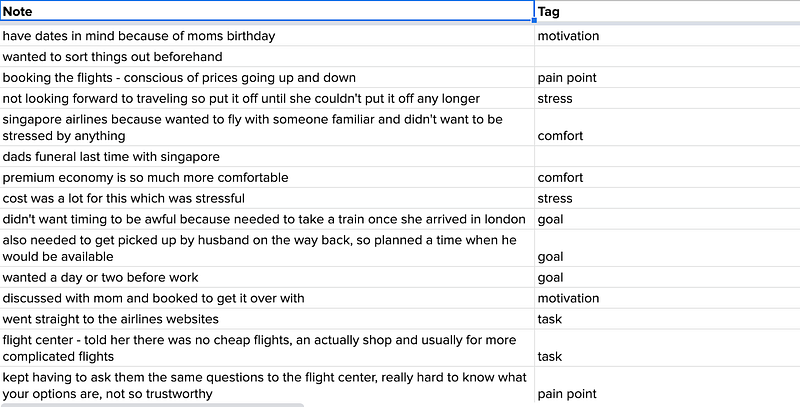

4. Pull together the information. Read through all of the transcripts and notes that you have gathered from the research. One thing I do is tagging each important transcript line with one of the above points (motivation, pain point, goal, etc.). See an example below:

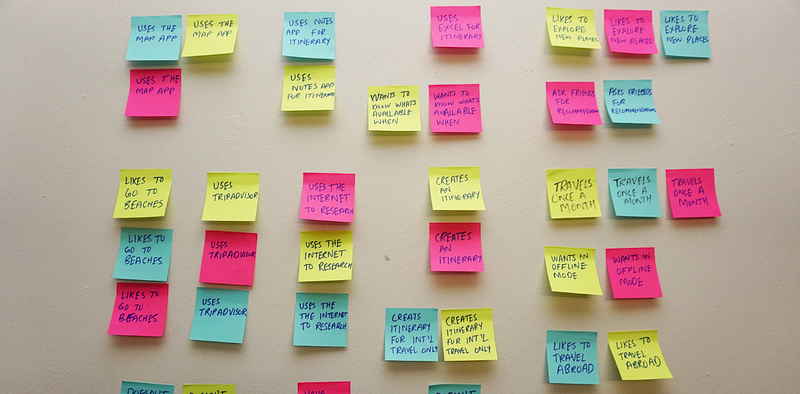

I then will create an affinity diagram with all the research I conducted and once I am done tagging. This is where I group all of the similar patterns I hear and cluster them into categories, such as motivations, values, pain points, etc. See an example below:

5. Outline the persona. Create version one of the persona. Include all the information you think might be relevant. Again, we are trying to help teams understand motivations of why someone acts the way they do, why they might use a product, and also tell a story of that person.

6. Design the persona. Putting this information into a visual format is the last step. Try not to do this before you have all the information together. Additionally, you don’t have to go crazy with graphics, as they usually aren’t helpful for a team. There are these bars that indicate people’s personality traits on a spectrum, and they are infuriating to me. They aren’t beneficial at all to a team making a decision. Keep the persona simple.

My most significant piece of advice when creating a persona: don’t just blindly use one of the many templates available. Although some may be beautiful (while others are undoubtedly ugly), they won’t serve you. First, come up with your goal and the relevant information needed for that goal. Then start creating the visual.

My second piece of advice: don’t make anything up. Delete all false or dramatized information. It will only get in your way when making decisions and could lead the team astray. You want your personas to be based on real user data.

I will do a more in-depth case study highlighting what this might look like with a real-life example. Until then, I hope this was helpful!

User research isn’t black & white

And how to navigate the grey area.

Recently, I was thinking back to when I started my career in user research. I was a Google machine. I looked up and read everything I could about the field. What I found most prevalent were the “User Research Best Practices” lists. There were many of them floating around the internet, but they all had something in common. They all told us what not to do.

I sat there, with my head full of the knowledge of what not to do in a research session, but didn’t have nearly as much information about what I should be doing. How was I supposed to navigate a messy situation? The negative reinforcement was doing nothing to move me forward, but instead creating an air of fear that I would mess up and get fired for ruining a company’s strategy.

Still, after many years in the industry, I continuously come up against this concept of all the things we are doing wrong in the field. The thing is, I agree with them. It isn’t as though I believe we should be leading our users and asking future-based biased questions during our interview sessions. However, the world is rarely so black and white, and companies are rarely so easy to navigate with a list of best practices. Oftentimes these best practices go out the window, given a stakeholder, situation or uncertainty with how to tackle something. So, instead of speaking in these black and white manners, let’s acknowledge and embrace all the grey in this world of user research.

Things we are doing wrong (or the deadly sins):

- Asking future-based questions

- Asking yes/no questions

- Leading the user with biased questioning

- Ignoring what the user is doing and placing too much importance on their words

- Asking double-barreled questions

- Not being open to the user’s answers

- Interrupting participants

- Speaking too much during the interview/filling the silences

- Validating concepts from upper-management

For real though, and maybe I shouldn’t be honest about this, but sometimes I commit these sins. Sometimes I ask yes/no questions to get a conversation started. Sometimes, in a moment, I ask a biased question and do my best to backtrack. I don’t think it is realistic to juggle all of these points and have a natural conversation at the same time. In addition, some of these best practices are extremely vague and don’t offer much guidance in the “correct” direction.

The problem I have with these best practices

Again, so I don’t seem like a crazy user researcher, I do think we should avoid pitfalls and use the best practices. However, many of these best practices are constructed as if we live in a perfect world of black and white. Very rarely are situations, especially those in user research, black and white. In fact, they are largely grey. And that is where I struggle with these lists the most.

User research isn’t, and will probably never be an exact science. We can’t always be perfect, and flawlessly execute a research session. We are humans, not robots, and I think that is 100% fine. We bring a level of empathy and perspective that would otherwise get lost.

Maybe some people call this bias, but I think it allows us to interpret research in a human and empathetic way.

Since the field of user research is so new and often misunderstood, we can get backed into a corner by stakeholders wanting specific questions to be answered. And also stakeholders who want specific answers to questions. Rarely are we working in an ideal environment for the best user research practices.

The thing is, conversations are h̵a̵r̵d̵ nearly impossible to predict. Trying to construct the perfect interview may end up making participants feel uncomfortable since it could feel very contrived. Either way, we always run risks. Risks are inherent when you bring two people together to unravel thoughts or perceptions.

An example: subscription box

Say you are working for a tech company that specializes in selling computer parts. You have identified a huge portion of the user base are gamers, who are constantly modifying their laptops, or building new computers for themselves and friends.

With this knowledge, stakeholders want to start a monthly subscription box with cool computer parts and coupons to various popular games. They essentially want you to validate this hypothesis as quickly as possible to push out this product. In the best terms: they want to roll out this product as quickly as possible, without pushback.

In this scenario, you are faced with the following challenges:

- Managing stakeholders expectations

- Asking about potential future-based behavior

- Predicting whether or not a user would buy something

- Forcing the user to think about a specific solution (subscription box)

- Asking potential customers about the price they would pay for such a service

- Getting a yes/no answer to interest in this specific solution

That list violates much of what we, as researchers, “should not” do. But, these scenarios are our day-to-day reality and happen more frequently than ideal situations.

So…what can we do in a situation like this? Here is my approach:

- Set expectations for stakeholders on what user research can do, and what it cannot do. I make it clear that user research is not used to validate what we want, but to explore whether or not a hypothesis is valid. We might not hear what we want to hear. Warning: they may not listen

- Recruit current users who have subscribed to a recurring subscription box in the past. If you can’t find any, that may be a sign that this is not for your target audience. In the case that you must run the study anyways, find users who know of people who have subscribed to a recurring subscription box. If this isn’t possible, recruit current users

- If you are, in fact, able to get users who have subscribed to a recurring box in the past, fantastic! Your job just got easier by mitigating the problem of asking for future behavior. In this case, the best way to predict future behavior is through past behavior. Whenever I am trying to anticipate whether a user will or won’t use a certain product, I ask them about their past experiences with something similar. I ask what they enjoyed about a similar product, and what they would change. This gives a good indication of whether or not we are going in the right direction

- If you are not able to get users who have subscribed to a recurring box, you are in a bit more of a tough spot. For this, I try to relate the question to something similar. Have they signed up for any recurring service? I try to mention common services, such as a gaming subscription (ex: World of Warcraft), Netflix or Amazon Prime. This way I can at least get a pulse on what they think of the above. This may give me some insight into how to structure the service. I then would ask them if they have any bought any computer part (or whatever we would offer) packages for themselves or others. This would then give me an idea of what they were buying together

- If I could find no current, churned or potential users who did any of the above, well, then I would caution against the idea in general. I would tell stakeholders I don’t believe there is a market fit in this particular area, with this particular audience. If they forced me to do the research (which some have), I would have to resort to asking future-based questions. At the end of the day, they are paying me. When you get backed into a corner, and no one heeds your warnings, there is little more you can do. I have refused to do the research, and it resulted in my freelance gig ending early. Spoiler: the product I was asked to do research on failed.

- After asking users about their past behavior (assuming we found users who subscribed to recurring boxes), I then pry into as many details as possible:

- What is the box like?

- Do you know anyone else who receives this box? Have you ever given it as a gift?

- How often does it come?

- What are the contents? What is the quality of the contents?

- What do you love about? Hate about it?

- How would you improve it?

- Do you currently still subscribed to it? Why/why not?

- What would make you stop subscribing to the box? What would make you a lifelong customer? (Yes, future-based, but still interesting to think about)

- What is the price? How do you feel about this price?

This information will give me insight into how we could structure a potential subscription box that would appeal to this audience. Of course, user research isn’t a straight answer and doesn’t guarantee success, but it gives us a direction to go with.

7. Asking about prices is always difficult and, in the example I mentioned, I ask for the price of a comparable product. This is the absolute best I can do, even if I am relating the computer subscription box to Amazon Prime, it is better than flat out asking someone how much they would pay for a hypothetical subscription box. Even if the two services aren’t equal, it gives me an idea of how they think about price and value for a service

8. I must admit, and maybe this is a sin, but I do float the actual idea by users at the end of an interview. I like to gauge their initial reaction when I mention an idea, such as the computer subscription box. I don’t base my entire interview on how they react to the idea, but it can give a decent indication of interest level. If you’re lucky, you get some really honest users, although most aren’t because of a variety of psychological phenomenon

9. Once I mention the idea to users, sometimes I will ask point-blank: would you use something like this? Would you subscribe to something like this? What would you expect it to be like? What would it contain? How much would you pay for it? In the end, I ask all the wrong questions because I spent fifty-five out of sixty minutes doing my best to ask all the right ones. Just because they are the best questions doesn’t mean they can’t give us any information. Again, I don’t base my research findings on these last five minutes, but I try to dig as much as I can out of the users, even if it is hypothetical

10. If I found very little interest in subscription boxes, both past and the potential current, I have to present a “failed” idea to stakeholders. Whenever I do this, there are two ways it can go: they listen or they don’t. In any case, I never just present that the project failed and that there is no way such an idea would ever work. I present alternative routes or ways to improve the proposed offering. At least, with this, there is a higher likelihood the stakeholders will listen to some insights and make the product as best as possible

Ultimately, what we are trying to do when asking about a future product is to understand the user’s mental models. How do they currently think about subscription boxes, specifically those for computer parts? How do subscription boxes fit into their day-to-day life? How do they enhance it? Or take away from it?

This is our goal, and we must remember it. Nowhere in that goal does it say you must never utter yes/no questions, or that you must never try to predict future behavior.

I would love to hear more about what you would do in this situation — my perspective only goes so far and I am excited to hear how others would tackle this.

Let’s adapt our research situations to realistic guidelines

We’ve established that user research tends to sit in a grey area, so what can we do in the future. The purpose of this post is to make sure we all know, especially those just beginning in the research field, that things won’t always be perfect. You may have to do research you don’t believe in and I am sure you will have to deliver results that are directly opposite of what stakeholders want to believe.

Instead of attempting to force user research to fit neatly into a chaotic environment, or trying to make an inexact science perfect, let’s allow user research to continue being what it is: human-centered. We don’t need user research to be perfect and we don’t need to always be the perfect researchers. What we do need is to remember our goal, and use whatever we can to get to that goal. Ultimately, it is about the users, not the practice.