Where did all the user research methodologies go?

A call for going beyond your usual methods

User research has become more popular as companies see the value in empathizing with and appreciating users. However, I believe user research is beginning to be defined as three central components: research interviews, usability testing and creating actionable insights. Let’s also throw in analyzing quantitative data in the mix, too. Recently, almost every job description I have read has a combination of these components, of course in all different types of language. I always love seeing interesting phrases such as, “you are keenly aware and able to observe/deconstruct the nuances of human behavior.” Sure, of course I can.

While I won’t argue that user research isn’t those three components, I will say, it can also be so much more than long conversations or validating/disproving prototypes. Many researchers know this, but I think it is easy to get stuck in a familiar and comfortable place, repeating the same methods, especially when you worked so hard to get user research buy-in from the start.

A case for different methods

I was having a conversation with a friend the other day and she asked me what some of my favorite user research methods are. I responded immediately with “you really can’t lose with those 1x1 in-depth generative sessions.” However, we know how difficult some it can be to plan time around a generative research initiative and it might actually not be the best method for the project’s goals. So, here I am, making a case for some other, less popularized, methods, which could lead to different insights and an understanding of the depth of user research.

Card sorting

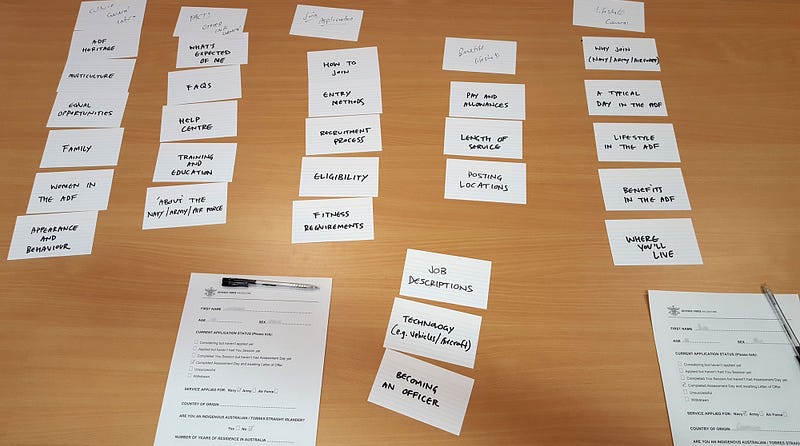

I’m starting with a method that is definitely used, but not as frequently as it could be. Card sorting is one of the most powerful information architecture research tools (and extremely fun/fascinating to facilitate). This method illustrates the way users group, sort and label content in their heads and can lead to extremely insightful information when it comes to designing IA, workflows, navigation and site maps. Not only is it a relatively “low-tech” research option (some index cards and sharpies or Optimal Workshop), you can use card sorting in several different scenarios:

- Open card sorts, where participants write their own cards and category labels, are great for discovering how users group content and think about flow.

- Closed card sorts, in which participants used your predefined labels, can be helpful to validate information architecture prototypes.

- Allowing users to sort cards by level of importance can show hierarchical data on what features/information should be surfaced or worked on first. Also leave a pile for “things I don’t care about,” to avoid building useless features.

- Enabling participants to write their own labels and cards, or cross out and rewrite anything you have predefined can help with aligning language to user’s mental models — this way the information you provide is relevant, understandable and helpful.

If you remind participants to think out loud during these card sorting exercises, you are bound to collect even more beneficial data about their reasoning and frustrations. Overall, card sorting can lead to many useful insights for various areas of your product.

Mental models

I first learned about mental models from Indi Young and have never looked back. When I started my career in user research, I quickly learned about personas and customer journey maps as visualizations of how users thought and behaved. I wanted to dig in deeper since, within every phase or overarching goal a user has, there are many different steps and opportunities potentially leading to an improved experience. That is where mental models came into the picture.

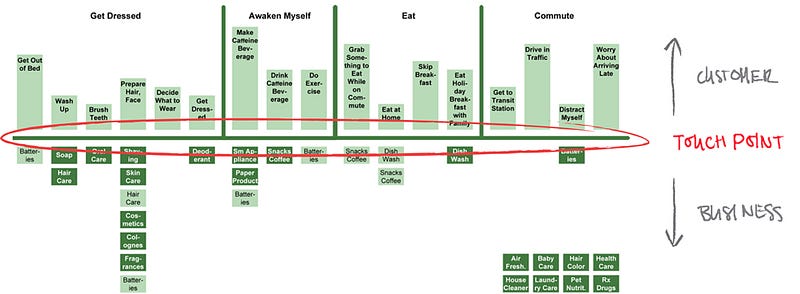

A mental model is a person’s intuitive understanding of how something should function and serve as a frame of reality. They are formed based on experience with everyday situations, activities and tasks. A great example of a mental model is the process one goes through when waking up, getting ready for work and commuting. Most people “streamline” this process into a routine and then create certain expectations on how this routine should go. This is also why we get so mad when things don’t go “our way” — maybe you ran out of toothpaste or the hot water isn’t working in your apartment or your subway gets stuck in the underground vortex between Brooklyn and Manhattan.

While your product might not be trying to solve these particular problems, the same expectations and feelings are formed when people are using apps, products or services. Before even using your app, users might have a mental model based on the concept your app represents. For instance, if you developed an online shopping app, there is a very large chance your future users have already formed a mental model around online shopping, expecting a specific sequence of events that align with their past experiences and their ideal flow. If you design a user experience that aligns with these mental models, you are able to bring delight. If not, there will be gaps in the experience, potentially leading to disappointment, frustration and disengagement.

To create a mental model, you speak to users are what they are doing to achieve certain goals. For instance, what are the tasks they are completing (or trying to) when they wake up or get ready for work? Does this include changing their clothes three times or going back home to make sure they unplugged the curling iron? You start to recognize patterns in people’s tasks and group them together under the overarching goal. Once you have understood the routine and journey people go through, you can then focus on the other half of the mental model: the features or products that would support these tasks. For example, how could you support a user when they are deciding what to wear or grabbing coffee on-the-go?

The outcome is a diagram, which helps in two ways: understanding how your current offerings do or don’t support users and also helps build user-centered design and strategy moving forward. Mental models are a wonderful tool to use in addition to personas and journey maps, or they can be used on their own to create deep awareness, understanding and empathy.

Co-design/participatory design

This method can go a few different ways. The most common usage of co-design is bringing together internal stakeholders and team members to discuss a problem and brainstorm different ideas and solutions. This can be a really fun exercise to engage stakeholders during the research/design process and to inspire creativity (there is always more than one solution).

Another way I have used this concept is at the beginning of usability tests or generative research sessions with actual participants. There was a usability test I was running, and I wanted to understand how users imagined both the concept and the task I was about to test. It was extremely hard to describe without biasing the language, so I grabbed a pencil and paper and started drawing out and talking about an imaginary scenario. As I was drawing, I said, “Imagine an app offered you a certain product and you wanted to change it to a different product. Can you list some words that would describe that concept and show me how you would expect the see it?” Once users saw how terrible I was at drawing, they had less qualms about drawing in front of me. They started listing wonderful words we hadn’t even considered and drawing interactions we couldn’t have thought of ourselves. We also were able to get some price points for the concept. After speaking with about seven users, there were clear patterns in word choice and interaction.

It isn’t always possible to employ this method, and I would actually recommend that it isn’t the only method you use, but instead take ten minutes out of a generative research session or usability test to try this out. It is a great exploratory and creative method to generate further ideas and potential solutions.

Expand your methods!

It is easy to fall back on repeating the same methods, especially when they are effective and the team trusts the insights, but there is so much more to user research than in-depth interviewing and usability testing! Not only will you show the team different methods that are better suited for different project goals, but you will save yourself from becoming a research robot! I would love to hear of any less popular research methods others are trying!

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]