My step-by-step user recruitment process

And don’t worry, I don’t have a high budget.

Honestly, recruiting sucks. It is one of the most challenging, time-consuming, and tedious parts of my job. Every time a research project comes across my desk, I sigh internally thinking about the recruitment process, especially if there is a tight deadline.

Since the responsibility of recruiting will never entirely disappear, I decided it was time to implement a process. I wanted to make recruitment as easy as possible through a standardized method and with as many templates as I could. My goal was to make recruitment mindless, and something I could do on the fly, in between meetings.

Of course, not every part of recruitment can be streamlined, especially the first parts of brainstorming about which participants are best. I tend to take more time in the beginning stages to ensure the right participants are selected to get the most optimized research results. Below is my thought process before I even begin writing an email to potential participants:

Before recruiting

Approximate your user

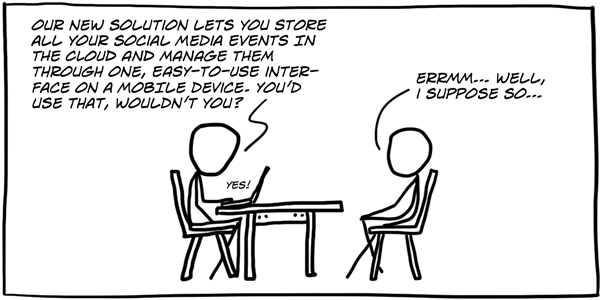

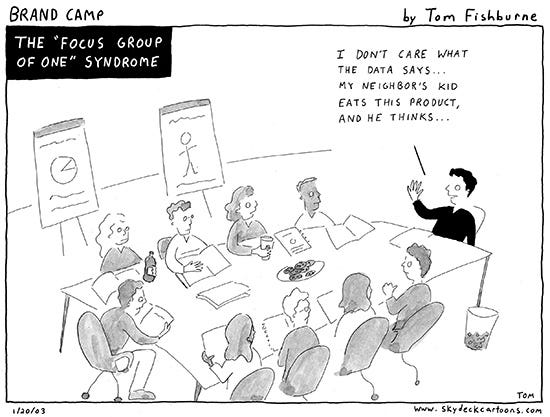

Before we even start recruiting, we have to understand who our users are so we can optimize our recruiting efforts. Talking to the right people is a fundamental part of doing proper research. If you don’t end up talking to the “right” people, your research may result in a complete waste of time and effort. What are some ways to do this?

- If you don’t already have personas or a target audience, take a day to sit in a room and define your target user. Bring in internal stakeholders that may have a good idea of who the target user will look like (such as marketing, sales, customer support), and come up with proto-personas. These are, essentially, wireframes of personas that consist of hypotheses about who your user is, and are a great starting point for who you should be talking to

- Look at competitors similar to you, and recruit based on their audiences. You can even recruit people who use the competitor’s product, and during the interview, ask them how they would make it better — a bit of a bonus!

- Sit down with the team who requested the research and ask them what type of participants and information they need. Is there a particular behavioral pattern? Is it necessary they have used your product (or a competitor’s product)? Do they need to be a certain age or hold a specific professional title? Gathering this information will ensure you write a great screener, which will collect you the best participants

My Step-By-Step Recruitment Process

Once I have my screener survey written, I am off to the races. Well, the slow races. I will take you through a sample project I recently, to illustrate how I am currently recruiting participants. And, as I mentioned, the budget is small.

Sample Project: We want to test a potential product concept idea with 7–10 users of our platform. Ideally, they will have traveled three or more times in the past three months, and have bought tickets through our website or app. Ideally, this research will be completed and reported on in three weeks.

- Approximate the user. Since this particular project came with predefined criteria, it was easy for me to set the underlying demographics. We needed a mix of our current users for a product idea. Recently, we had decided to focus on a slightly younger demographic, so I included that strategy in my decision as well.

- Create a screener survey. Once I had the basic idea of who I wanted, I went ahead to start forming questions to get me the right participants for the project. I knew it had to be people who traveled three or more times in the past three months, and who have used our website/app to do so. I asked for demographic information, such as age, gender, and income, to understand how different users interact with our website/app. I then put this on Google Forms to easily send a link for people to fill out, which is free! See my example screener here.

- Pull newsletter subscriber emails from the CRM. Since I now work in the EU, GDPR rules are more strict than in the US. I can’t merely spam people who use our website/app. To get around this, I work with the email marketing team to pull newsletter subscriber emails from our CRM. When users sign up for our newsletter, they give us the right to contact them for user research sessions.

- Individually email users screener survey. With these emails in hand, or rather, anonymized on my computer, I set aside a large chunk of time to email each user. Since we can pull up to one thousand emails at once, I usually leave this task for the later afternoon, when my brainpower is already going downhill. In this email, I include a link to the screener survey, why we are contacting them, and, of course, compensation.

- Post a recruitment survey via HotJar. We were fortunate enough to get a business subscription to HotJar finally. They have a portion of their product dedicated to recruitment surveys, which pop up on the website. I include the screener survey there.

- Respond to any email inquiries. My Google form responses come in nicely to Google sheets, where I can see all of the information beautifully laid out. For everyone who “passes” our criteria needed for the study, I reach out to them with the session information, a consent form, and reiterating compensation. For those who do not “pass” the criteria for the particular study, I try to fit them into another research project. Also, keep an eye out for any questions potential participants might ask.

- Email calendar invitation. I use Google Calendar to send requests. I always double-check the timing and keep a consistent format for the subject of the calendar invite: Participant name x My name: company name feedback session. Within the calendar invitation, I reiterate the vital session information (how long the session will be, my email, etc.) and include a link to a Zoom meeting. I make a separate calendar invitation in which I book a conference room and invite all my colleagues.

- Email a session confirmation 12–24 hours before. The probability a participant will attend a research session goes up if you email them a reminder 12–24 hours before the meeting. In this email, I reiterate the necessary information, including a link to the Zoom conference room, and the consent form if they have yet to fill it out.

- Always send a thank you email. Regardless of compensation, or anything really, I always send a thank you email to the participant no more than 24 hours after the interview. In this email, I include specific topics we discussed, as well as the compensation voucher. Additionally, I encourage them to reach out to me with any questions or feedback in the future.

See all of my recruiting, scheduling and thank you email templates here.

Although it is still time-consuming, I have managed to decrease the amount of time I spend recruiting. In my case, the email templates have been especially helpful in speeding up the process. In the time since I started, I have managed to convince the team to invest in some great time-saving (and free/cheap) recruitment tools:

- Calendly

- Doodle

- Google Forms

- Typeform

- Zoom video conference

- HotJar

As tricky as recruiting can be, it isn’t impossible with a tight budget, or as a team of one. Just hunker down, create some streamlined templates, and enlist your patience.

Have a ‘difficult’ participant? Turn the beat around

How to deal with interesting participant personalities

While I shy away from calling anyone a “bad” participant, I do know, as user researchers, we can come up against some pretty difficult and interesting participant personalities. This can make for really unfruitful conversations. When we only have time and budget to talk to a smaller amount of users, we want the conversations to be as rich and productive as possible. Although we can sometimes become accustomed to playing the role of a psychologist, babysitter, flight attendant and juggler, there is no reason we can’t try to turn these situations around.

Working with a variety of participant types is part of a researchers job. As we go through these experiences, we get better at handling each, unique situation, and are more adept at staying open-minded in the face of adversity. This is a skill you can only learn by encountering these scenarios.

What are some of these personalities?

There are many participant personalities floating around, but I wanted to list out the common ones my colleagues and I have seen. If I had the design skills, I would love to make them into personas, but, alas, I am merely a researcher.

- Vicious Venter. This person agreed to the research session, not to help, but to make sure you know he/she hates your product, and all the ways your product has messed up his/her life.

- The Blank Stare. Every time you ask a question, you receive a confused look. This participant speaks very little and is, seemingly, unsure about how to use technology.

- Distractions Everywhere. Bing, bong, boop. Any distraction available will take the attention away from the interview.

- No Opinions. No researcher likes to hear the words, “it’s fine” or “it’s pretty good.” When you dig, you hit a cement wall. It is almost as if there are no emotions present.

- The Perfectionist. One of the most difficult participants for a usability test, since they really want to make sure they are doing everything perfectly. They will often ask you more questions than you ask them.

- Tech-Savvy Solutionist. They could have built a better app, and they will tell you how.

- Your New BFF. Because of social desirability bias, some participants may try to befriend you or make sure everything they say is kind or flattering. Almost the opposite of the vicious venter.

- The Self-Blamer. They will blame themselves for the problems they encounter, instead of the system, and may get easily frustrated.

- The Rambler. Will often go off-topic and speak about irrelevant information, making the sessions unproductive.

Tips on tough participants

Yes, we have seen these personalities come up, but what can we actually do in these scenarios?

First off, take a deep breath. Normally, when you have a difficult participant, it could actually be your fault. For instance, the time wasn’t taken to make the participant comfortable, or they feel like you aren’t listening. It is important to go through a checklist to ensure you did everything on your side to make the research session as enjoyable as possible.

- Vicious Venter. We don’t want to interrupt the venter, because that generally doesn’t help the situation, so we have to find ways around this. I try to divert the conversation by saying, “I understand what you are saying, and I want to get back to that later on, but I would like to focus on this…” Another option is actually trying to listen by going on the journey with the venter, and using some quotes for insight.

- The Blank Stare. It can get frustrating when participants are very unsure about how to use technology, but try your best to resist the urge to immediately help the participant. Let him/her struggle through the process for a little, take note of it and then intervene so you don’t spend the entire session watching the participant on one task.

- Distractions Everywhere. Ensure there are as few distractions in the room as possible, such as cell phones, computers, even clocks. Additionally, try to make the environment as quiet as possible, with few people walking by the room. I often ask the participant to turn their phone on silent and place it away for the entire session.

- No Opinions. Make sure you ask open-ended questions as often as possible, as it makes it more difficult for participants to answer with lackluster statements. And, if they do, dig. If something is “fine” or “okay,” ask them why. Ask, what is “okay” or “fine” about it or what do they mean when they say “fine?” I will also ask, “how would you describe this to someone who has never seen it?”

- The Perfectionist. Whenever a participant asks me a question, such as a perfectionist asking, “is that right?” I turn the question right back to them, “what do you think?” Stress that there are no right or wrong answers in these situations, and you are just interested in their honest opinions.

- Tech-Savvy Solutionist. It is very easy to focus on solutions when you have a tech-forward participant, especially one who wants to tell you how to do things better. Always remember to focus on the problem. Yes, they may want all of these features, but why, what problem are they trying to solve or goal they are trying to achieve.

- Your New BFF. Stress how important honest feedback is. When faced with social desirability bias, it can be difficult for people to give critical feedback. Always encourage this type of information. To help, I mention no one in the room designed what they are giving feedback on, and that there will be no hurt feelings.

- The Self-Blamer. Remind this participant there are no right or wrong answers, and that usability tests are, in fact, not tests. During usability testing, I will refer to tasks as activities, as this takes the pressure off. Additionally, I will reassure a flustered participant that other participants had similar problems (which I tend not to do as this can introduce bias), so they may feel more at ease when encountering problems.

- The Rambler. It is exciting to find a person who wants to share a lot, but, oftentimes, ramblers can be off-topic, which can lead to very unproductive conversations. Similar to the venter, it is important to always try to steer the conversation back to the relevant topic, by using segues such as, “that is really interesting, and I want to circle back, but for the interest of time, could we focus on…” And just doing this over and over again to try and get as many useful insights as possible.

Overall tips for avoiding these situations

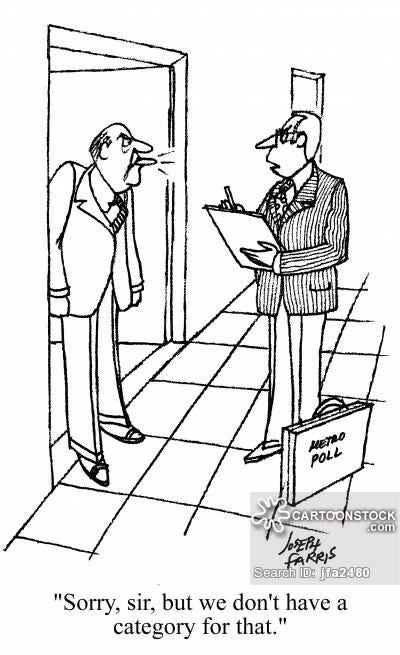

- Recruiting. Really think about your recruiting strategy. If you find you are getting participants that aren’t the best fit, take a look at how you are screening participants. Are you sure you are asking for the right criteria?

- Seize the moment. Even if you do everything right during your recruiting, some less than ideal participants can still slip through the cracks. In addition to the above techniques, it is important to use these situations to your advantage. Even though it may not be the best interview you have ever conducted, you can still get something out of it. Don’t just give up, use it as an experience to learn!

Do you have any experiences with the above? Or something different? I’d love to hear about any of your stories with different participants, and how you mitigate these different personalities or scenarios.

As a note: I don’t really think there are “bad” participants — there are some that are less ideal for certain projects, but none of them are downright awful. They serve as great learning experiences on how to improve our perspectives and practice.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

ACV laddering in user research

A simple method to uncover user’s core values.

Have you ever been in an interview where you feel you are so close to uncovering something crucial about the user’s behavior or motivation? For me, it happens quite often. I know there are shallow ways to respond to user research questions, and most participants respond in that way. Sometimes I do it myself when my students are interviewing me, simply because, it takes an awful lot of self-awareness to truly answer a question with a deep-rooted motivation. This is especially the case when you are sitting in front of a total stranger and they ask you to talk to them about how you use a product.

The above is the exact reason why we have widely known methods such as TEDW* or the 5-why’s techniques*. These methods get the user to open up and elaborate on their answers by focusing on open-ended questions, memory recall and stories. With these approaches, you can get much more emotional and rich qualitative data, including more deep insights into the participant’s mind.

The best thing a participant can do is tell us a story — we get all the context from someone who engaged in activity naturally, and we also get their retrospective opinion on the past. Although recalled memories can be “false,” we care most about their perception.

We have these tried and true methods, yes, but sometimes it simply doesn’t feel like enough. I can open up the conversation with all the TEDW questions in the world, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I will get to the core of a participant’s thought process or behavior. How do I get the most out of my (short) time with participants?

Enter the ACV ladder.

Where did ACV laddering come from?

Laddering was first introduced in the 1960s by, who other than, clinical psychologists. It was presented as a way to get through all of the noise in order to understand a person’s true values and belief system. It became so popular because it is a simple method of establishing a person’s mental models, and it is a well-established tool in the field of psychology. Yes, we aren’t psychologists but…

Being a user researcher sometimes feels like I am simultaneously trying to be a therapist

This methodology didn’t just pop out of nowhere, but is based on the means-end-chain theory. Since I don’t want to bore you with a long discussion on this (although I am totally a nerd and obsessed with this stuff), I will succinctly summarize:

The means-end-chain theory assigns a heirarchy to how people think about purchasing (because everything comes back to money):

- People look at the characteristics of a product (shiny, red car)

- People determine the functional, social and mental benefits for buying the product (I can get from point A to point B, I get a new car, the car is cool)

- People have unconscious thoughts about values that align with their reasoning for the purchase (A new car makes me feel cool, which makes me feel young, which, ultimately, makes me feel important and less insecure about my age, looks, etc.)

I know I mention only in the last point that thoughts are unconscious, but they tend to be fairly unconscious throughout the entire process.

Anyways…

So, what is ACV laddering?

Essentially, it is a type of probing that gets to a core value. ACV laddering breaks down the means-end-chain theory into three categories:

- Attributes (A) — The characteristics a person assigns to a product or a system

- Consequences © —Each attribute has a consequence, or gives the user a certain benefit and feeling associated with the product

- Core values (V) — Each consequence is linked to a value or belief system of that person, which is the unconscious (and hard to measure) driver of their behaviors

How do I use ACV laddering?

When we start to understand the different areas of the ACV ladder, we can identify where a participant is when they are responding, and try to urge them forward towards core values. For example:

- Q: Why do you like wine coolers? (Assuming the participant has indicated they do like them)

- A: They are less alcoholic than other options (attribute)

- Q: Interesting. Why do you like them because they are less alcoholic?

- A: I can’t drink as many as other types of alcohol, which is important (attribute)

- Q: Why is that important to you?

- A: I don’t get as drunk and tired (consequence)

- Q: And how does not getting as drunk and tired impact you?

- A: Well, I don’t want to look like a drunk…it is important for me to appear sophisticated (consequence)

- Q: Sophisticated?

- A: It is important for me to get the respect of others, and it is hard to do that when you’re drunk (core value)

With ACV laddering in mind, it is easier to pick up on attributes and consequences to, ultimately, get to someone’s core value behind their actions or thoughts. This also helps you get the most from your participants!

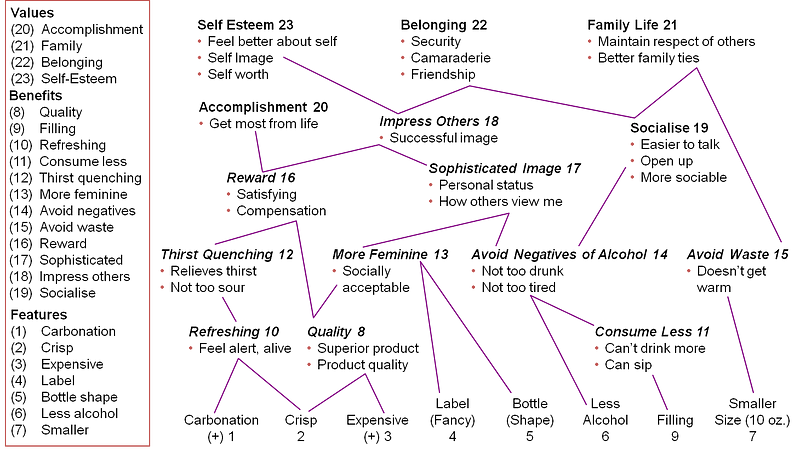

This information can then be used to create a hierarchical value map, which displays the ladder with the participant’s responses into a very visually stimulating map.

When you use ACV laddering, you get very concrete insights that are much deeper than whether or not someone liked something, or even a story they recall. This can really impact the user experience of a product, from how it is displayed, how the copy is written, how it is sold, the micro-interactions within a product, the colors and the even the order of screens shown to a user. Essentially, it can have a huge, company-wide impact.

I am using laddering to level-up as a user researcher and bring my team (and beyond) even better insights. What do you think?

*

The TEDW approach uses the following words to open up conversation, as opposed to asking yes/no or closed questions:

- “Talk me through/tell me about the last time you…”

- “Explain the last time/explain why…”

- “Describe what you were feeling/what happened…”

- “Walk me through how you…”

The 5-why’s technique is to remind us to ask why five times, in order to get to the core of why a participant is saying what he/she is saying

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Defining your User Research philosophy

Why are you a user researcher?

Questioning and exploring your beliefs as a user researcher can be extremely important, as it can help you develop your philosophy of user research. This helps you understand and articulate what you interpret are the best approaches to user research, and why you are a user researcher. Examining your thoughts behind the research process, such as methodologies, recruiting, notetaking, analyzing and sharing, can help you define your own process, and give others a good understanding of how you approach and implement user research into a company. Before you are called for an interview, this statement, along with your résumé, will give your possible future employer a first impression of you. It can also be extremely helpful when trying to build a research framework at a company.

I think, as user researchers, we do a lot of reading and learning; we try to understand the best techniques for the given situations, we discuss different methods and ways of conducting research, we try to list best practices for every aspect of the research process. Bottom line: we ingest a lot of information. What do we do with that information? We try to apply it and put it into practice to see what happens.

As we progress through our careers, I believe we start to shape our own understanding of user research processes, and tend to develop patterns on how we approach problems. We have spent much time piecing together all of this incoming knowledge to inform us, but have we taken time to define our own process, with all its unique twists and turns? Maybe it is time we sit down and think about our philosophy of user research and how we got there.

Questions to help define your philosophy of user research

- How do I think? What is my set of beliefs based on: past experience, personal ideals, surrounding knowledge, schooling, classical ideas?

- What is the purpose or value of user research?

- What is my role as a user researcher?

- How should I evangelize and share user research? Do I transmit information to teams or take a facilitator approach?

- What is the role of the company in user research? How can each department respond or help me with conducting, analyzing and sharing user research?

- What are my goals as a user researcher, both inside and outside of a company? How do I contribute to the user research community?

- Why am I a user researcher?

I definitely have my own framework and process that I bring to each research project, my own way of thinking, however, it was only after being in the field for over 5 years that I actually sat down to define my own user research philosophy. And that was just recently. Maybe I am a bit behind the curve, and people do this regularly!

The act of formally sitting down and answering these questions was immensely helpful for me. Not only did it reiterate the fact that it is important for me to understand where my own thoughts, perceptions and biases come from, but also that there are other ways to approach problems outside of mine. Additionally, I can better articulate my beliefs and framework, which help others in understanding where I am coming from and what my process might look like in a given project.

Aside from the user research project, it also helped me in remembering why I became a user researcher and all the things I love about this profession. I restated my goals, which also remind me of my motivations and values. For me, this was an invaluable exercise that helped me redefine my goals, and for the people I work with to better understand who I am as a user researcher.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Running a Design Studio Based on User Research

A workshop to turn user research insights into solutions

I once used an insight as a solution. Straight from the user’s mouths: “we want to be able to buy clothing in the certain way.” I loved it and thought it was a great idea. There was one small problem: creating that feature would pretty much mean creating a new product for the company, which would require a lot of time and work. However, it was an insight from my research. We made it. No one used it. Flip flop, the product was dead. Not only did this cost the company money, it drained my team of time/resources and made it that much harder to re-convince people that user research is a worthwhile process. To say I was mortified would be an understatement.

Why am I telling that short (and tragic) story? It is to relay the fact:

User research gives you insights, not solutions.

It is really cool when people are excited about and using your research insights in order to inform designs. The only problem is, more often than not, you can’t just take the user’s solution verbatim and create a product/feature. I will never say never, sometimes it works, particularly in very obvious cases, such as redesigning small parts of an interface or including a feature everyone has been begging you for. However, the majority of the time, using customer’s solutions directly will not get you to the best solution.

Just because user research isn’t giving you the direct solution to a problem or question, it is giving you information in order for you to make an informed decision. Informed decisions are better than making decisions either 1. based off of nothing or 2. based off of your gut/intuition. User research will give you a window into how users are thinking about things, but that doesn’t mean they know how to properly design the experience of said feature they “need to have right now.”

What is a design studio?

Instead of taking these insights and turning them directly into solutions, products or features, there are better ways to use user research to get to unbelievable ideas and UX. One of those ways is by running a design studio based on user research insights. A design studio is a meeting that brings together stakeholders from different teams to create ideas from user research insights through sketching, discussion and iteration. Overall, design studios help you explore problems, create many designs and unify teams.

There are a few reasons why design studios can be beneficial:

- External stakeholders are able to get excited about research and flex the creative side of their brain, which many product managers and developers don’t often have the opportunity to do

- Allows stakeholders (and yourself) to turn user research insights into actual ideas (otherwise known as solutions, I just hate the word solution)

- Enables the team to come up with many different ideas as opposed to the one that your user mentioned. User research insights should almost always be translated into multiple ideas, unless it is a very simple change

- Everyone gets a chance to contribute — I invite developers, product managers, sales, marketing, solutions architects and basically anyone I can get to contribute. With this many different people and perspectives in the room, I can get a lot of unique approaches to the same problem

- Similar to above, but running design studios lead, oftentimes, to innovation. Not only may you find a very creative answer to the problem in front of you, but you might also gain insight into other ideas or research projects you could be running

How to run a design studio

There are a few ways to go about doing this, as there are with most things in life, but I have a process I generally follow that has yielded great results in the past. Generally I only run design studios for larger problems or areas of exploration. Very rarely will I schedule people’s time for a more simple bug fix or smaller, iterative change. I will break up my process into several different areas.

Part 1: Prep

Before you run a design studio, you definitely need to prepare yourself, especially if this is your first. Here are the different steps I use to prep:

- Assign a moderator. This is typically me. The moderator is the one that will lead the entire design studio, keep an eye on time, keep participants on track, bring energy and enthusiasm and will not participate in the actual activities

- Set an agenda*. My agenda is fairly detailed; it includes objectives, any homework* and potential outcomes. If I’m inviting participants who have never experienced a design studio, or I am new to a company, I will include a short informational powerpoint on why design studios are important and effective

- Create a short presentation. I always have a powerpoint ready as it makes it easier to get everyone’s attention when starting the design studio and ensures we are all on the same page. My presentation includes: what a design studio is, what we will be doing and the problem we are trying to generate ideas for. I also include sample sketches from previous design studios: this helps people visualize what we are trying to achieve and also eases people’s minds if they don’t feel comfortable drawing

- Decide on participants. As I mentioned, I will invite as many departments as possible. I usually cap my design studios anywhere from 10–12 people, so that might mean running two separate groups.

- Invite people. I will generally check people’s calendars to choose a few days that are best. I give 2–3 options depending on how many sessions I will be running, and let people choose which is best. Each session is about 75 minutes long (although I always wish I had 90, it is often tough to schedule that long). I also make sure to include a clear agenda with objectives and any homework* the participants need to do

- Print out design studio templates, which make it easier for people to sequence their sketches, and bring them to the meeting with many pens and pencils

- Arrange for food, whether this be lunch or snacks and drinks. I always bring food, such as cookies, chocolates, pizza, etc. I once held a design studio at the end of the day on a Thursday. No one was particularly thrilled until they walked into the meeting room and were greeted with beer and cake

*I have outlined a sample agenda at the bottom of this article

*Homework generally includes participants reviewing the relevant research by rereading research summaries, rewatching research sessions or looking back at research notes. I like to ensure stakeholders remember the relevant insights before we start trying to solve for them

Part 2: Beginning the design studio

These are the steps I take while running the design studio. I have included approximate times for each step, based on a typical 75 minute studio.

- 5 minutes: Have everyone introduce themselves and the team they are on/department they are in. Sometimes all your stakeholders will be teammates, but I have run many design studios where people in different departments have never met!

- 3 minutes: Run through what a design studio is, as well as the agenda. I always tell participants I will be timeboxing the meeting, which means I will be very aware of time, and people might have to stop working mid-sketch or mid-sentence. I also announce that absolutely everyone has to draw.

- 3 minutes: Present the problem, answer any remaining questions and tell everyone to take a few sheets of paper. I reiterate that everyone has to draw

Total: 11 minutes

Part 2A: Running the design studio

During this part of the design studio, I leave the agenda up, which outlines each activity we will do and the amount of time associated with it

- 8 minutes: everyone takes 8 minutes to sketch as many different solutions to the problem as they can. There is not limit to the ideas — they can be as wild as people want them to be. There are no wrong ideas. Remind developers and product managers not to think technically, but, instead, creatively. Give participants 2 minute warnings

- 5 minutes: each participant chooses their favorite sketch and posts them on to the board

- 15 minutes: each person has about 1 minute to pitch their idea to the group

- 5 minutes: everyone takes another 5 minutes to sketch as many ideas as possible again

- 5–10 minutes: if people would like to exchange their favorite sketch with a new one, they can post it on the board and get 1 minute to pitch their new idea

- 5 minutes: the group votes on the top three ideas/sketches. This can happen a few ways: the moderator can provide each person with two colored stickies and they can sticky their top two choices, the three sketches with the most stickies are considered the three chosen. You can also present each sketch, have people put their heads down and thumbs up for up to two sketches. Either works, but I like to keep mine as anonymous as possible

- 5 minutes: participants give any feedback on the top three ideas/sketches

- 5 minutes: talk about follow up and answer any questions

Total: 53–63 minutes

Total time in part 2: 64–74 minutes

Part 3: Post-design studio work

Now that you have run your design studio, you have to provide follow-up to the participants.

- Write up the results of the design studio. This includes a big thank you, as well as a reminder of what you did and why, and then attach the three chosen sketches in addition to the others. Talk about how the designated designer(s) will mock up the sketches into prototypes, which will be tested in usability tests. Invite the participants to the usability tests

- Have the designer(s) turn the sketches into prototypes and run the usability tests. Be sure to share the results with the team and get them excited for the next design studio!

Design studios are a really great tool to get people excited about user research and creating ideas based off of research. These types of exercises really help when trying to evangelize user research. If you are having problems convincing stakeholders to attend, look up sample design studios and show them the results, it can help. I encourage you to run your own design studio and see how it works! Also, comment back, I love hearing from people :)

7 user research hacks

Not the best practices..but not the worst.

I was talking to my boyfriend, a research-friendly product manager, and he had mentioned, yet again, how hard it is to do user research when there isn’t someone dedicated to the task, and when others in the company aren’t sure how to do research. This isn’t the first time I’ve heard something like this. In fact, I hear it a lot. Oftentimes, there aren’t enough resources to properly conduct user research, whether that be time, budget, people or processes. Normally, I would argue, “there is always time, money or anything else for user research.” Instead, I decided to answer with some user research hacks.

The reason I am sharing these hacks is not to enable people to skip user research, but to encourage companies to start research, in the smallest way. From there, you can start to build on a user research practice. Again, this is not a replacement for user research but, if you are able to get some good results from these hacks, you can get buy-in to continue growing user research in your company. (Although some of these make me want to share the monkey with his hands over his eyes emoji).

My top user research hacks (eek)

- Emailing users for feedback

This is always my first go-to when I think about user research hacks. It can feel a bit like cold-calling (cold-emailing), and doesn’t always have the highest success rate, but it can lead to some really great results. The way I go about this is emailing them, asking them if they would be willing to provide feedback on a certain feature or concept idea. I offer three ways they can give feedback: hop on a call, have them record themselves and send it, have them respond back via email. I offer different levels of incentives for each option. - Internal user testing

I have used internal testing at nearly every company I have worked for. To begin with, it is a great way to learn about the product in general, but it is also a wonderful method to get (sometimes very valuable) feedback from people who care about the product. Generally, I will start with account managers, customer support and sales, as they generally have the most contact with customers and understanding of what customers might want. When I do internal testing, I book a time and room, get snacks/cookies/pizza and send out an email asking for interested parties. Usually, within the hour, I fill up most of the slots, making it incredibly fast. Also, I get to evangelize UX research across the company! - Look for research studies online

Many people have done research on many different things, so, chances are, there are studies out there that cover similar topics you are looking to understand, For example, N&N group have many studies available online for you to read, including information on how users interact with the products (which may be similar to yours), what satisfies them, what angers them. Another wonderful way to understand your users is to look up studies you competitors have conducted. These don’t have to be your direct competitors, as they may not have data available online, but you can extrapolate to a competing company that would have information online. I recommend doing this, either way, before (or during) research, in order to learn as much about the market and industry as possible. Another option here is to look at your app reviews, or those of your competitors! - Use analytics (or previous research) to help make decisions if you can only talk to a few users

Although I primarily conduct qualitative user research, I have very high regards for quantitative data, and how it can show crucial information about a user’s interaction with the product. If you are only about to speak to a few different users, you can understand the patterns they perform, and use supporting data to validate or disprove the hypotheses you made. You can also use analytics tools, such as HotJar and FullStory to watch how users are interacting with your product. Data only gives part of the story, and can’t really answer the question why, but is a great tool to use when you are strapped for time and participants. It is also important to use data in conjunction with qualitative research, as they are incredibly complementary to each other. - Keep a panel and recycle

Maybe you have run some user research sessions before, and you are looking to test some new ideas or prototypes, but are struggling to find new participants. One hack is to think back to your previous research sessions and try to identify which sessions went well. Usually, after a research session, I write down whether or not the research session was successful and I ask if the participant is okay with my contacting them for future studies, so I know if I can recycle the participant. It isn’t the most effective method to get research insights repeatedly from the same set of people, and can introduce some bias, so don’t use the same people every single time, but, if you need participants, recycling isn’t cheating. - Street & coffeeshop (guerrilla) research

If you have already done enough internal testing, or you don’t have the ability to do it, you can always take your prototype to the street, coffeeshop, mall, what have it, and perform some guerrilla research. Of course, this depends on your product. If you have a very niche product that only a specific user base benefits from, this may not be the best method for you. However, if you have a more broad product that can be used by the masses, guerrilla research can be your friend. It isn’t the most reliable way to research, but it can give you some good feedback to help propel you forward. It is pretty tough to approach people when, usually, they just want to be left in peace, but there are a few ways to make it easier. I have set myself up in a coffeeshop (my neighborhood Starbucks was super nice letting me do this), with a sign on my computer asking people for 30 minutes to talk about X, Y or Z for a free drink/food of their choice. People were surprisingly interested, and I had five people who sat down and spoke with me in the span of four hours. They weren’t the most insightful interviews I’ve ever conducted, but I did get some information that helped the team make our first round of decisions. - Use customer support

Is there a customer support team or someone who deals with customer support/tickets? If you have a customer call line, it is incredibly helpful to listen into calls. Although you can’t guarantee you will get a specific call about a certain area of the product, it is very insightful to understanding the most common problems your customers are having, and potentially, what you could do to fix them. Another option is to filter and look through support tickets. With this, you can funnel down to support tickets containing issues you want to learn more about. In addition, and similarly to internal testing, it is great to speak to the support team members and the most common issues they are hearing. Speak to the support team members about what they’re hearing as well.

These may be controversial points, and they definitely stray from best practices, but they are a great way to get started with research, especially if you are struggling to get buy-in. However, these are not a replacement for the conventional qualitative research methods that should ideally be part of your user research process as and when possible.

[embed]https://www.slideshare.net/NicoleBohorquez/7-user-research-hacks[/embed][embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Stop (or traffic) light usability testing reports

A simple and effective way to visually convey usability testing results.

I sometimes struggle to find ways to present user research that is both digestible and actionable. Qualitative research tends to primarily include words, quotes, audio clips, etc. With this methodology, reports can become text heavy, and difficult or time-consuming for team members to read. This is especially tough if you are working with a new team, coming in for a short time as a contract worker or trying to convince people to actually read your research. However, qualitative research, especially usability testing, is extremely important to do, and to share across a company.

After several attempts to share usability test results, I found that stakeholders weren’t gaining the most value from my reports. I set out to find a different way. I started by talking to the stakeholders involved. I asked them what information was most important to them and effective techniques they have employed when sharing reports. With this, I could understand the hierarchy of information they needed and better prioritize my reports. From there, I did my own research into how to present usability test findings. Finally, I came to something called Stop Light (or Traffic Light) Usability Testing Reports and have adopted and adapted this as my method of sharing usability test results.

What are they?

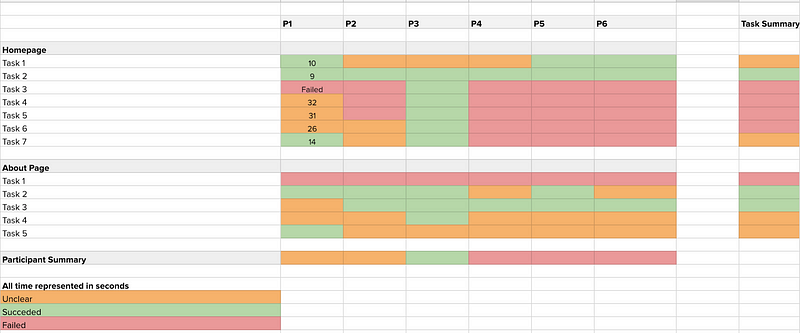

People do stop light reports differently, and I have seen different methods. I will share with you the way I set up my reports. They can show a few different things:

- Conveys whether or not a user has passed a usability testing task

- Includes how severe the problem is in a task

- Shows amount of time spent on a task, by task and participant

- Averages how many participants passed/failed a given task

- Summarizes how the usability test went through visuals

The most valuable part of the stop light approach is how visual it is. It can easily give a stakeholder a holistic overview of how the usability test went. Additionally, I have put in more information, including:

- After the usability tests, you can put UX recommendations based on the results of the sessions, and link them to the different tasks. If you want to, you can also color code these similarly, that way it is all in the same place with the same format!

- This is also a great place to include notes on the participant, either by someone who is taking notes during the session, or can be added in after. That way, you can link certain notes up to the given task.

- Shared assessments by all stakeholders watching the research session. Each person can work directly on the same document (I use Google Sheets), and rate the usability test on their own. By doing this, you can see if your stakeholders also thought the participant was unclear about a task, integrating stakeholders into the research and making the research more valuable.

How do I do this?

In the spirit of visuals, instead of just explaining stop light tests, I want to share a visual example of one of my reports (it is all dummy data).

In the above example, there are different components:

- Each participant has their own column, with a participant summary at the bottom

- Each task has its own row, with a task average summary all the way over to the right

- The three colors indicate whether a participant succeeded in a task, was unclear in the task or failed the task — these can also be used as severity ratings. The red are the most important fixes, orange are medium priority and any problems within the green tasks are left for lowest priority

- The time for each task is recorded within the taskXparticipant bubble and can be averaged per task

There are a few things you have to do before you go out and start using this approach when sharing your usability tests.

- Make sure to define what passing, succeeding and unclear mean for each given task — this is something you discuss with other stakeholders (designers, developers, product managers)

- It is also beneficial to benchmark and average how long tasks generally take users. That way, this data is useful. For example, if task 4 on the homepage usually takes users 10 seconds to complete on the current product, and it is taking users over 30 seconds on the prototype, that is a huge red flag. If you don’t have any benchmarking data, it might be worth doing some benchmarking before you go out to usability test

- Get some buy-in! Before I started sending these out to my stakeholders, I presented the idea to them and they actually gave me some great feedback that made the transition easier and more valuable for everyone involved

Overall this approach has really helped me clearly and effectively share usability testing results with colleagues, and has given them much more value than a written report. It makes it easy for people who just want to glance at the results, to understand what the priorities are (summary), but also gives the option of digging deeper into the results (notes) and includes actionable insights based on the test (recommendations). Download the template I use here.

Again, there are many ways to do this, and I’d love to hear about your approaches or feedback!

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

A user research-focused course

***JANUARY 2021 UPDATE: Since posting this, I have heard from many of you about how you appreciate this idea. Because it is very difficult for me to support so many classes while working full time, I have created a website with updated course availability.***

The number one question I receive from people who are interested in getting into user research, or who are just beginning their career, is “what courses should I take? How do I learn more about user research?” I have yet to discover a good answer to this question. There are a few different options I bring up: taking a UX course (I taught part of one at Pratt), watching online tutorials or reading blogs/books.

I have a few qualms when recommending the above. Watching online tutorials and reading blogs/books, honestly, is great, but only gives you so much. It is very hard to learn a profession through just reading or watching. This is the reason I tend to recommend a UX course. Now, when I talk about UX courses, they are generally not focused on user research. Instead, they include the whole field of user experience, and highlight UX design, rather than research. Research tends to play a small part in the larger picture of the course.

There are very few courses out there that actually focus on cultivating a UX research career. Additionally, there are few university degrees relating to user research as its own career. Luckily, I majored in Psychology so I have a “research-background,” but Psychology research (and working in a mental hospital) is much different to UX research. However, it is difficult for people who are interested in become user researchers to take a course centering around starting a user research career.

I have learned so much from the research community, and have been so lucky to meet such compassionate and wonderful teachers — I only hope to pay it forward. This is why I am looking to put together a user research course to offer people who are interested. It is completely free. The only stipulation is, the first classes will be beta testers, and will have to give me feedback!

What will be covered?

In this 12–week live course, we will meet twice a week for three hours per class. In between, there will be homework (fun and inspiring, I promise). I will be breaking the class down into four core modules:

- What is user research and how does it fit into a company?

- How to conduct and share user research

- User research strategy

- Research portfolios and case studies

Each of these modules will cover the essentials of user research, such as methodologies, notetaking, stakeholder buy-in, timelines, recruitment, biggest challenges of a UX researcher and much more!

During the 12 weeks, there will be lecture, discussion and, most importantly, interaction/practice. We will be taking the lessons we learn in the class and actually practicing them. I will take the time to critique research plans, notes, interviews, etc. What I want more than anything from this course is to give people a space to practice and simulate what it means to be a user researcher. In addition, there will be a project each person works on throughout the course, so there will be a concrete portfolio piece at the end.

Why am I qualified to teach this course?

Well, I’m not particularly sure how qualified I am, but I’ve taught user research at Pratt University in New York, I’ve spoken at conferences/meetups, worked in a variety of companies/environments and I’ve done a lot of learning. I’m sure there are plenty of other people out there who are more qualified than I am, but I love teaching and empowering others and I would like to impart the knowledge I have gained so far. So, if you are willing to try this out with me, I would love that!

The classes will be open to four people. Again, completely free of charge, I just request (honest) feedback. The course will start in February of 2019.

If you are interested in this course, please fill out this Google Form (by January 3rd, 2019) to give me a better understanding of why you would like to take the course!

I would also like to run a user research portfolio workshop in January 2019, so please let me know if there is interest in that, as well. Feel free to reach out to me with any questions or comments: nikki@productherapy.com

I look forward to hearing from you!

First-person surveys in User Research

Making surveys more personal

Surveys can be looked at as a controversial user research methodology. At one end, they give a large amount of quantitative data, which makes stakeholders feel more comfortable making decisions. On the other side, they turn users into numbers and don’t allow us to dig deep in understanding the “why.”

I know companies that rely solely on survey data to make data-driven decisions. They include comment boxes with the hope users will leave a message explain their survey response. I tend to leave responses, since I have user research guilt that requires me to give feedback to others, but I know the majority of people do not.

In my opinion, I don’t believe surveys are enough of a user research tool to drive better decisions, on their own. At times, I feel as though companies use surveys as a way to feel like they are being customer-centric. When you only use one method of user research, or use only quantitative or qualitative data, you are missing other pieces of the puzzle that can give you a more robust and empathetic understanding of your users.

But, there is a way to make our surveys more effective…

How could we use surveys effectively?

As I mentioned, using surveys as the sole methodology can be detrimental, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a place for surveys in a user research practice. Surveys can be a great complement to qualitative research and they give you big numbers, which helps with gaining momentum and buy-in.

We want our users to tell us stories about their experiences, even in our surveys. Stories are powerful because they tell us what the person actually did, instead of what they think they might do in a given situation. What people say they would do versus what they actually do can lead to two very different scenarios.

First-person questions push respondents to answer with what they actually did, instead of projecting potential future behavior in a given scenario or opinions. The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, so it is important to use this method regardless of the type of survey question. This is the way to turn a survey from an impersonal form, to something easier and more personal for a user to fill out.

For example:

- Third-person question: “What is the hardest part of our check-out process?”

- First-person question: “The hardest part I encountered during the check-out process was…”

I like using surveys in four different ways (There are many more reasons to use surveys, but these are my favorite):

- Providing an understanding of the direction your next qualitative research project should go in

- Validating/disproving hypotheses from qualitative projects

- Honing in on specific concepts that come out of other projects

- Receiving feedback on features

Other Tips for Phrasing Questions:

When trying to write effective surveys, keep these tips in mind:

- Make sure to focus on or include open-ended questions

- Keep the language as simple as possible (average literacy rate is around 5th grade)

- Make sure questions are short

- Watch out for double-negatives

- Avoid double-barreled questions (asking two questions in one)

- Include ‘I don’t know’ or ‘Not applicable’ options

- Don’t lead the user (don’t ask questions like, “how helpful is our app?”)

Types of Questions

- Likert Scale Questions (quantitative)

After using [new feature name] I would rate my experience as a [1(very bad) to 7 (very good)] - Follow-up Open-Ended Questions (qualitative)

I rated this feature as a [5] because __________ - Open-Ended Questions (qualitative)

If I could change anything about this product, I would ________

By using the first-person question writing technique, we can get truly authentic and personal responses through a survey, which is all you can hope for when conducting user research. This makes the controversial “survey as a user research method” a time- and cost-effective option for companies (in addition to other research methods, of course). Let’s look at how we are writing surveys by making sure they are delightful for our users, and allow them to tell us their stories.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

A comprehensive (and ever-growing) list of user research tools

Everyone in the UX field (and tech/product, in general) seems to really love tools. We all want tools to make our lives, and jobs, easier. We strive to find tools to solve the most common problems we face. There is a good amount of information out there on different tools, but I haven’t come across a comprehensive list dedicated to user researchers (other people in the UX/product field can also benefit)!

As researchers, we have a lot of different components to our job that we then have to bring together into a presentable and actionable insight we can present to our teams. With this, they can go out and make products better.

I have broken up the different resources into different areas/responsibilities of user researchers. A lot of these tools may overlap and make sense in different areas, but I wanted to try to separate them as best as I could. I will highlight some of my favorites and will link to everything I can. As time goes on, I hope this list only grows. Please comment with your favorite tools or recommendations!

User Research Tools

Slack Channels:

I wanted to start off with different slack channels I have found extremely helpful as a user researcher. These channels span across the world and offer information on jobs, resources, different discussions on research methodologies and more

- Mixed Methods

- Research Ops

- HexagonUX (all women)

UX Artifact Templates:

Honestly, Pinterest (follow my user research board) is a great way to find templates of UX artifacts, which can help non-designers get a little more creative when pulling together research. I have highlighted some of my favorite tools, and also some I have created myself. All of these are templates. You don’t have to follow them exactly, but they may give you ideas on how to visualize the research you have done.

- XMind (for mind mapping)

- Mini Heuristic Evaluation

- Empathy Map Template

- Persona Template (from UX Lady)

- Customer Journey Template 1

- Customer Journey Template 2 (scroll down — includes a Service Blueprint, too)

- Scenario Storyboard Template

Competitive analysis:

Competitive analysis may not be in every user researcher’s job description, but it is a good idea for you to properly understand the competition in the space. I have created both of these templates. The first is a much more high-level understanding of competitors, while the second dives much deeper into the details.

- SWOT Analysis Template

- Competitive Audit Template

Research Platforms/Databases:

Below are some options I have used before for platforms to recruit, conduct and organize research. Some tools have different abilities than others, but they are all fairly robust. One of my favorite tools for conducting remote card sorting or IA sessions is Optimal Workshop. They do a really great job with set up and post-research analysis. I also think Usabilla is a great tool for getting users to engage with quick surveys or research opt-ins.

- Optimal Workshop (including Optimal sort, Treejack and First Click Testing)

- Usabilla

- Uservoice

- Userzoom

- Validately

- Airtable

- Nom Nom

- dscout

Research Artifact Templates:

I have created a few templates to showcase what, in general, goes into a research plan and research report.

- Research Plan Template

- Usability Testing Plan Template

- Research Report Template

- UX Research Portfolio

- Usability Testing Metrics Spreadsheet

Recruiting:

I know I have already mentioned a few platforms above that are able to help you recruit participants, but I wanted to make a separate list for those I have used almost solely for the purpose of recruiting. If you are looking to recruit in the US, UserTesting is definitely a favorite and, for Europe, I would pick TestingTime.

- TestingTime

- UserTesting

- Ethnio

- Userzoom

Prototyping:

We may not need to make wireframes and design UX/UI, but we still need to work with designers on both of the above. My absolute favorite tools either for working with designers, or for when I need to create my own designs, are Sketch & Invision. The combination is wonderful and fairly fluid. This makes testing prototypes during usability tests easier. I also want to give a shoutout to Pop (by Marvel) for bringing paper prototypes to life, definitely worth a try!

- Sketch

- Invision

- Balsamiq

- Zeplin

- Proto.io

- Pop Paper Prototyping

- Framer (Sketch competitor)

Synthesis & Sharing:

Synthesizing and sharing results can be really difficult, both in-person and when your team is remote. Some of the above solutions in the research platform list (ex: Airtable) help with this. Below are separate tools I have found to help run synthesis sessions and share research results. My absolute favorite tool on this list is Mural.co, they have allowed me to easily hold remote synthesis sessions with teams across the world. My other favorite, for sharing, is Mosaiq, a customizable wordpress site. I have also showcased an example of a usability testing spreadsheet where I use the stop-light method.

- Post-its for affinity diagrams (because what research article would be complete without them)

- Mural.co (for remote synthesis)

- Aurelius

- Mosaiq

- Usability Testing Spreadsheet

- Notion

Notetaking & Transcription:

I haven’t come across many notetaking apps that are more effective than using excel, word, or getting your research sessions transcribed. The one that also offers analysis of your notes in Reframer. I used it briefly, but I am too in love with my way of taking notes on excel to move to a different tool. I have used very small transcription services in the past, but I have heard good reviews from these companies.

- Reframer (notetaking by Optimal Workshop)

- GoTranscript (transcription by humans)

- Temi (AI transcription)

Surveys:

There are many platforms that allow you to set up surveys, all with different capabilities. One of my favorites is Qualtrics, as it allows for some really nice question logic, and has some great analytics tools. If your budget isn’t there for surveying tools, something as simple as SurveyMonkey, GoogleForms or a Microsoft Word document can also be effective.

- Qualtrics

- QuestionPro

- LimeSurvey

- Typeform

- Sample Screener Survey Template (Microsoft Word)

Analysis (of Behavior):

Having a platform or tool that helps analyze user’s behavior on your app or website can be extremely helpful when pulling examples for research insights. If you don’t mind being creepy, FullStory or Hotjar are great tools that record sessions of users on your product, and allows you to watch them either live or later on. I have also found HotJar to be useful when trying to justify information hierarchy via heatmaps.

- Hotjar

- Optimizely

- FullStory

- Bugsee (mobile)

- Appsee (mobile)

Remote usability testing/interviewing:

Earlier I mentioned some robust research platforms and recruiting tools, that also allow you to conduct interviews on the platforms, but I wanted to highlight a few tools in particular that are useful for remote usability testing or interviewing. My absolute favorite screensharing and video conference is Zoom, as it has many capabilities and is extremely reliable.

- Lookback

- Zoom

- Google Hangouts

- Userzoom

- UserTesting.com

Surveys

There are many usability surveys floating around out in the space of the internet. I have a folder that includes some of the top surveys, such as the SUS, QUIS and USE.

All of these recommendations and opinions are 100% mine, no sponsorship here, I’m not that cool or popular. I will continue to add to this list as I explore other tools and also as I hear from you about what your favorite tools are. Please drop a line to help this list grow and expand into a resource for all to use!

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

“We don’t need user research…”

The ability to convince stakeholders they need user research seems to be a more important job requirement than the actual ability to conduct research sessions.

I once had someone approach me and say, “you know what, user research is overrated.” This person knew I was a user researcher. I no longer talk to this person (not because of what they said in that instance, but their general attitude towards life).

Even though user research is becoming more mainstream and popular, dare I say it’s “trending,” there are still many challenges faced when thinking about implementing a user research practice into a company. The most common is getting buy-in from (usually) higher-level stakeholders. The ability to convince stakeholders they need user research seems to be a more important job requirement than the actual ability to conduct research sessions.

I have worked at companies where user research wasn’t particularly valued — some to the point where I seriously considered why they hired me in the first place. It was difficult to consistently have to be fighting for research, fighting for what I did (or was meant to be doing) on a day-to-day basis. When someone comes up to you and tells you how unimportant user research is, it can be infuriating and really defeating.

Usually, what I have found, are there are common misconceptions about user research and the value it brings. Typically, people shy away from the amount of time user research can take. What they may not understand is user research can fit properly into sprints. It doesn’t have to take months! My favorite (and simultaneously least favorite) argument, however, is:

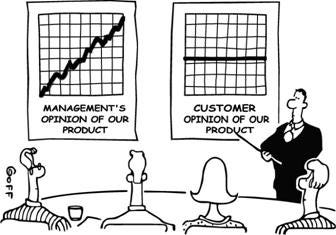

“We already know what our users want and need”

Now, this statement is tough. I can understand people’s rational fears of time, money, added value, and I can speak to those when I explain to them my plan for user research.What becomes more difficult, without research, is telling a higher-level executive they have no idea who their customers are and that they are wrong. For example:

Boss: “I think we should implement this new feature that makes customers rate our products they just bought before being able to browse new products.”

UR: “Why do you want that?”

Boss: “Because we can get more ratings on our product and make it more obvious how to rate.”

UR: “But how would that make for a better experience for our customers?”

Boss: “I’ve worked here for quite some time, I know what our users want. I think they’ll love it.”

UR: “ But how do you know they will love it? Based on my previous research projects, I’m not sure if they would. Maybe we should test this?”

Boss: “We don’t need to test it, that would be a waste of time. I know it’s a good idea, so that’s what we will do.”

This may be an extreme example (or maybe not), and I have definitely heard it before. You could argue the time issue here, but I doubt that is actually a concern. The most concerning part of this is the implementation of a feature without the thought of research (generative or evaluative), based on the fact that someone who has been working at the company, or in the industry, for some time just knows. When you have the opportunity to so research, it is best to choose that path rather than making the gut decisions.

So, here we are, talking about how we are going to implement a horrible new feature that will, most likely, dissatisfy or annoy our customers. As a user researcher, this is tough and we have all been here. I will ask two questions: why is this happening? What can we do to solve this?

Why is this happening?

This boss is a person who is trying to make the best decisions based on the information they have in front of them — which is their experience and understanding of the customer, regardless of how right/wrong that is. The answer may seem illogical, but this response of “I know what is best” is a fall back tactic when you don’t have the time to explain your rationale. This rationale might be something you are familiar with or it might be something completely outside your mind, such as “the CEO said this” or “I need to hit X numbers by a certain date” or “I saw data that said this was a good idea.” Just because they are thinking this, doesn’t mean they will explicitly state their reasoning. In addition, the boss is probably interacting with many people during the day, who are saying what decisions should be made and giving their own opinions on situations. Out of all those people, you are only one voice.

What can you do?

Most of the time, I would like to prove the boss wrong and to show them actual user research that disproves their hypothesis. I want to push the research. I want customers to be happy. What if, instead, we try methods that give the boss more tangible solutions rather than “we need to research that.”

Boss: “Implement this rating feature!”

UR: “What an interesting idea. I’d love to run it through our research process, where we test next features to make sure users value them, and they work with our current product. We do this to make sure customer satisfaction, acquisition and growth metrics stay high. By testing any changes before implementing them, we are able to know that we are iterating towards success, keeping business KPIs up, and not just making changes because someone has a feeling”

Or

UR: “That would be a great addition to the test we are running this week. I’ll make sure to send you the results as soon as we have them in about two weeks, so you can use them for further conversations.”

Or

UR: “Have we done previous research on the benefits of that feature?”

Boss: “No”

UR: “Let’s put a prototype together in the next few days. We can go out and guerrilla test it with our users — I would love it if you could join us.”

Or

UR: “Let me talk to the team and come up with some potential benefits of that feature, including how and when users would use it. Can I get that to you by the end of next week?”

Bottom line, offer a solution with a tangible artifact at the end, so the boss has something they can reference or use. Although it may sit in their back pocket, there is a much higher chance they will be more open to the discussion in the future if you give them something. Eventually it could turn into a more consistent and user-focused process.

Bosses are only as much of an antagonist as you make them. Tell them about the different actions you can immediately take to give them something real, and they may just take your side.

An aside

In one way, I will agree, there are certain times where user research doesn’t fit in, but I will tweak the saying a bit: you don’t need half-assed user research. This may be controversial. A lot of people may say, “any research is better than no research.” Sure, in theory, that is correct. When you need something, any of that thing is better than none of that thing. The difference, however, is that research can be done wrong. And it can go wrong fairly easily with those who may not have the proper understanding or training. Doing half-assed, improper research can actual hurt the company and prohibit them from finding a researcher, or someone knowledgable in user research to help them down the road. A now and a future problem.

Benchmarking in UX research

Test how a website or app is progressing over time.

Many user researchers, especially those who focus on qualitative methods, are often asked about quantifying the user experience. We are asked to include quantitative data to supplement quotes or video/audio clips. Qualitative-based user researchers, including myself, may look towards surveys to help add that quantitate spice. However, there is much more to quantitative data than mere surveys and, often times, surveys are not the most ideal methodology.

If you are so lucky as to be churning out user research insights that your team is using to iterate and improve your product, you may be asked this (seemingly) simple question: how do you know your insights and recommendations are actually improving the user experience of your product? The first time I was asked that question, I was tongue-tied. “Well, if we are doing what the user is telling us then, of course, it is improving.” Let me tell you, that didn’t cut it.

Quickly thereafter, I learned about benchmark studies. These studies allow you to test how a website or app is progressing over time, and where it falls compared to competitors, an earlier version or industry benchmarks. Benchmarking will allow you to concretely answer that above question.

How do I conduct a benchmarking study?

1. Set up a plan

You have to start with a conversation with your team, in order to agree on the goals and objectives of your benchmarking study. Ideally, you answer the following questions:

- First and foremost, can we conduct benchmarking studies on a regular basis? How often are new iterations or versions being released? How many competitors do we want to benchmark against and how often? Do we have the budget to run these tests on an ongoing basis?

- What are we trying to learn? How the product is progressing over time? How does it compare to different competitors? Understanding more about a particular flow? This will help you determine if benchmarking is really the right methodology for your goals

- What are we actually trying to measure? What parts of the app/website are we looking to measure — particular features or the overall experience? How difficult or easy it is to complete the most important tasks on the website/app?

2. Write an interview script

Once you have your goals and objectives set out, you need to write the script for the interviews. This script will be similar to how you write usability testing scripts, questions need to be focused on the most important and basic tasks on your website/app. There needs to be an action and final goal. For example:

- For Amazon, “Find a product you’d like to buy.”

- For Wunderlist, “Create a new to-do.”

- For World of Warcraft, “Sign up for a free trial.”

As you can notice, these tasks are extremely straightforward. Don’t give any hints or indications on how to actually complete the task. That will completely skew the data. I know it can be hard to watch participants struggle with your product, but that is part of the benchmarking and insights you can bring back. For example:

- “Click the plus icon to create a new to-do.” = Bad wording

- “Create a new to-do” = Good wording

If you would like to include additional questions in the script, you can use follow-up questions, asking them to rate the difficulty of the task

After you complete the script, and once everyone has been able to input any suggestions or ideas, try to keep it as consistent as possible. It is really difficult to compare data if the interview script changes.

3. Pick your participants

As you are writing and finalizing your script, it is a good idea to begin choosing and recruiting the target participants. Although normal user research studies, such as qualitative interviews or usability testing generally call for fewer participants, it is important to realize we are working with hard numbers and quantitative data. It is a really good idea to set the total number of users to 25 or more. At 25+ users, you can more easily reach a statistical significance and draw more valid conclusions from your data.

Since you will be conducting studies on a regular basis, you don’t have to worry about going to the same group of users over and over again. It would be beneficial to include some previous participants in new studies, but it is fine to supplement that with new participants. The only important note is to be consistent with the types of people you are testing with —did you test with specific users of your product who hold a certain role? Or did you do some guerilla testing with students? Make sure you are testing with those users for the next round.

How often should I be running benchmarking studies?

In order to determine how often you should/can run the benchmarking studies, you have to consider:

- What stage is your product at? If you are early in the process and continuously releasing updates/improvements, you will need to run more benchmarking studies. If your product is, further along, you could set the benchmarking to quarterly

- What is your budget? If you are testing with around 25 users each time, how many times can you realistically test with your budget?

- If you are releasing updates on a more random basis, you could come up with ad-hoc benchmarking studies that correlate to releases — this just might not be the most effective way to show data.

You really want to see progress over time and how your research insights are potentially improving the user experience. Determine with your team and executives the most impactful way to document these patterns and trends. Just make sure you can run more than one study, or the results will be wasted!

What metrics should I be using?

There are many metrics to look at when conducting a benchmark study. As I mentioned, many benchmarking studies will consist of task-like questions, so it is very important to quantify these tasks. Below are some effective and common ways to quantify tasks:

Task Metrics