Introducing doubt into User Research

Are we allowed to be wrong and iterate?

I recently co-organized a user research meetup here in Berlin (check us out, if you are interested). The topic was on personas and archetypes — fascinating and intriguing. We started with a talk by Smava, and then proceeded to split up the room into several groups to further discuss certain questions pertaining the topic. I was moderating one of the groups. Our question was:

How do we continuously evolve personas/archetypes, and continue to make them actionable for our teams?

Heavy question, but, I must admit, I was psyched to discuss this with my group. The conversation ended up going in a way I could have never imagined, and it still crosses my mind weeks later.

Our themes

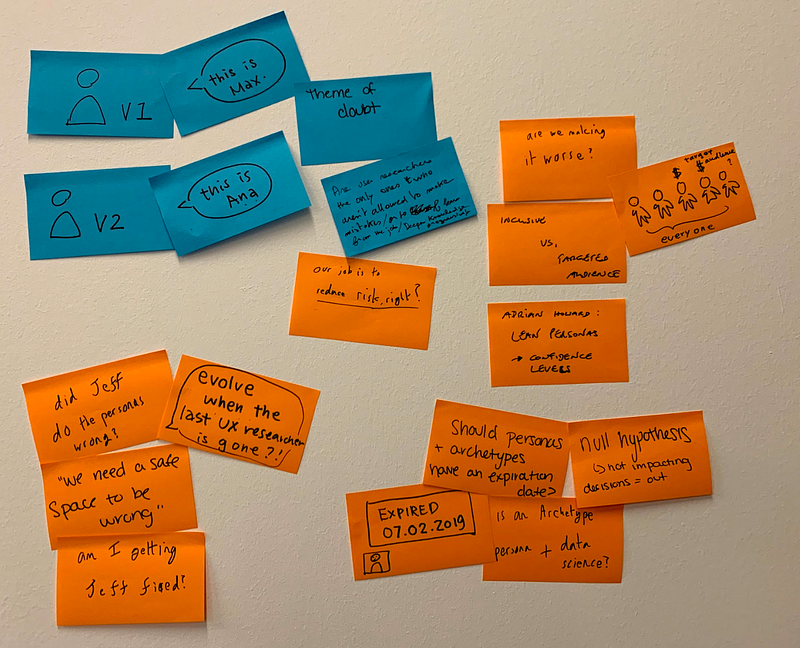

We had about thirty minutes to discuss the above question, and none of us had ever met each other before. We had no idea where we came from or what experience any of us had with personas. So, we did what any other researchers would do: we went straight to the sticky notes.

While we started the discussion on evolving prototypes and making them actionable, the conversation started to evolve towards different themes/questions:

- Can we doubt user research?

- Should personas/archetypes have expiration dates?

- How do we set up personas/archetypes so we can evolve them?

I wish I had a transcription of the conversation, since it was filled with fascinating twists and turns, as well as common anecdotes of the challenges we face as user researchers.

I am going to tackle each theme, in reverse order, since, I think, they all can be held under the umbrella of doubt.

How do we set up personas/archetypes so they can evolve?

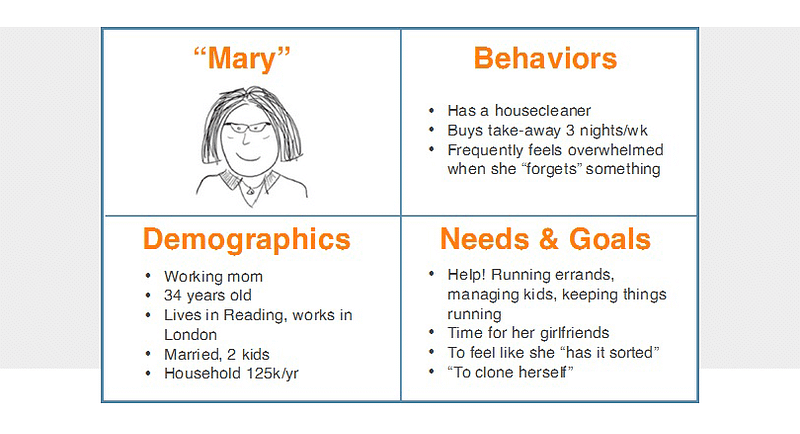

The concept of lean personas (or proto-personas) is an extremely popular concept. These types of personas are something I have used in previous companies, but they always led to a more finalized, and dare I say, “pretty” persona that ended up being more or less static.

Adrian Howard came up with the concept of the lean persona, which is, essentially, a more skeletal wireframe of a persona. There is less information, more concise formatting and it is definitely less visually aesthetic. Lean personas are great for startups or when there aren’t many resources available to create “real personas” (I kind of want to call them fat personas, but I digress).

However, lean personas can also be used to create sense of dynamism — the persona isn’t pretty or concrete enough to be static, instead, it can be shaped and iterated on. It can evolve with the research, the product and the team. People can write on it, cross things off. You don’t need to be a designer to edit a lean persona.

Expiration dates on user research outputs

I’m using the word output here for a specific reason: when I say output, it means things like personas, customer journey maps, and different visual representations of user research, not the outcomes of research.

Have you ever joined a company (or even been there for a bit) and asked, “where are the personas (or any other output)?” only to be met with a scrunched up face and the response, “ooo, I think John made them a while ago…I’ll send you the link to them.” You finally obtain the link and you look at the personas. You can almost see the layer of virtual dust accumulating over the surface, and some virtual cobwebs starting to form in the corners. These were so hidden, it is pretty clear no one has used them. You slack your coworker:

You: Hey, thanks for these. Could you tell me John’s last name? I would love to set up a meeting with him to discuss these.

Your coworker: Oh, John left the company a while back.

Essentially, these personas, created by (poor) John have simply been sitting here gathering dust, which is the killer of all things actionable and productive.

Maybe there is another way to prevent this from happening. We brainstormed a few different ideas:

- Expiration dates. What if outputs had expiration dates, best until 6 months from creation. That way, people are forced to look at the outputs, at least, every six months, in order to evaluate how (and if) they are working. This also helps respond to changes in the product, market and company

- A three month retrospective. If no one has used the outputs to make any sort of product decisions or improvements, they need to be seriously reevaluated. If the team isn’t using them, they are officially not actionable, which renders them rather useless. By doing a retrospective every three months, we can keep outputs alive and relevant

- The Null Hypothesis. This one is fascinating to me. Microsoft works with the null hypothesis concept, they assume things are wrong, until they are proven right. If you create an output assuming it is wrong, you will need to prove it is right, which means you will be constantly looking at and using the outputs in order to validate them

Introducing doubt

All of these concepts boil down to this final idea of doubt. As user researchers, we need to be okay doubting our research, because, we need to tell people it can change: outputs can changes, insights can change (or be wrong), users can change.

Are user researchers the only ones who aren’t allowed to make mistakes or learn from the job?

We generally spend so much time convincing people to see the value of user research, and to buy-in to this still foreign concept of speaking to users. With this, it is terrifying to admit mistakes or to tell people something might change. We believe, when we open up this avenue, we may lose the trust or support we worked so hard to achieve. In fact, it should be the opposite:

We should be able to question our own work and insights

Outputs should be able to change and be iterated on, even when they appear “done”

Users and research should be able to grow through time, and still have a high amount of value

Doubt doesn’t have to be bad, in fact, it can keep things from staying static, and allow them to breath and evolve.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]