How I got into User Research

From the first time I heard about user research to my first internship.

Since I was young, I had my sights set on becoming a vet or a psychologist. My parents laughed at the thought of me being a vet. If I saw an animal even stub their paw, I’d be in tears. I spent a brief time shadowing a vet when I was younger. I lasted about 2 hours before I ran out crying, swearing off my future as a veterinarian. I then dove into my second option, psychology.

Since I was young, I had my sights set on becoming a vet or a psychologist. My parents laughed at the thought of me being a vet. If I saw an animal even stub their paw, I’d be in tears. I spent a brief time shadowing a vet when I was younger. I lasted about 2 hours before I ran out crying, swearing off my future as a veterinarian. I then dove into my second option, psychology.

During my Master’s program in Psychology, I worked in a mental hospital a few days a week. The patients I longed to work with had mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and dissociative identity disorder (it exists). I worked with these patients in the hospital and criminals in a neighboring hospital to get this experience. Over the two years, I completely burnt out and withdrew my Ph.D. applications.

I was terrified. I had some debt from school and no viable career ahead. All of my plans flew out the window. I grasped at straws to find the right job for me. Could I be an interior decorator? Or a motivational coach? Or maybe I could start my own business. I spoke to a few career coaches and still felt lost.

By some crazy stroke of luck, I user experience fell into my life. I was at a party (wallowing, I’m sure) when someone mentioned user experience. They told me it was about making website and app experiences better for whoever uses them. This idea was intriguing. I went home early and looked up this potential new career.

I fell in love

The instant I Googled user experience, I couldn’t stop reading. Everything about the topic spoke to me. There was something about user experience. It felt like a beautiful mix of psychology and technology. I believed I could use what I learned during my Master’s program and apply it to user experience. I thought it would be an excellent fit for me. Plus, it gave me a sense of control. I finally knew what I could do for the rest of my life.

The only problem was I cannot draw. Not for the life of me. To this day, I can’t complete a circle (it always overlaps) or draw easy shapes. Visualization is one of my weakest points. I can see what I want in my mind, but it is almost impossible for me to put it on paper (physical or digital).

I ignored this small hiccup and figured I could learn how to become a designer. Spoiler alert: that didn’t work. However, I am so grateful for moving forward since it brought me to user research.

How did I start?

I immediately filled my shopping cart on Amazon with as many books as I could find, including:

- Interviewing Users: How to Uncover Compelling Insights by Steve Portigal

- Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior by Indi Young

- Measuring the User Experience (2nd Edition): Collecting, Analyzing and Presenting Usability Metrics by William Albert and Thomas Tullis

- Handbook of Usability Testing: How to Plan, Design and Conduct Effective Tests by Jeffrey Rubin

And many more!

I then scoured the internet for any guides or blogs on the subject of user experience. I sat on Dribbble for ages, scrolling through people’s designs; I found designs on Pinterest (I still have a UX Pinterest Board — although now renamed to User Research); I read guides on how to be a user experience designer. Anything user experience, I ingested.

I then found General Assembly. General Assembly is an education platform geared towards tech- and business-related careers, such as coding, designing, digital marketing, and data analytics. They had two options for a user experience course: a full-time immersive course and a part-time course. Since I was working, I chose the part-time course. I started counting down the days until it started.

What was it like?

The General Assembly course primarily focused on user experience design. We learned about design thinking, prototypes, and different tools such as Sketch. Finally, we came to the section on user research. User research fascinated me. I wanted to know everything about the topic. While my design skills were lacking, my background in Psychology bolstered my interviewing skills. I felt so comfortable conducting user research (although I had no idea how much I needed to grow).

That course rocketed my interest and love for user research. I didn’t get quite enough training in research, but it motivated me to continue my learning and quest to become a user researcher.

I want to make a quick note here: you don’t have to take a boot camp or expensive course with a certificate to get into user research. You don’t need a MA or Ph.D. (although for some companies such as Facebook, it makes it easier to get an interview). All you need curiosity, compassion, and a drive to learn and practice user research.

That course did not (I repeat, did not) get me my first user research job. Hard work and practice made this career a reality, and I will outline each step I took to get into the field.

What happened next?

If only the world were magical and I landed a job right after finishing the General Assembly course. That was not the case. General Assembly was great for understanding that user research was a viable career and the basics. I had a lot of work to do after that course. My immediate next step was to start applying to jobs.

But, before that, I noticed a small caveat present on almost each job description: portfolio required. My heart sunk once I figured out what a portfolio was. I had my General Assembly project, but that wasn’t going to help me with user research jobs. I knew it wouldn’t be easy, but here is what I did:

1. I volunteered for a pet adoption agency and did some user research for them. I had already been volunteering for them, so I knew who to reach out to. I also did this for a few other pet adoption agencies where I didn’t have any contacts — I do so without them knowing, but it served as a portfolio piece. To get participants, I used guerilla research by sitting in a Starbucks with a sign that said, “If you have adopted in a pet in the last six months, talk to me for twenty minutes, and I will buy you a coffee and treat.” It was surprisingly successful

2. I picked two different areas I felt strongly about and researched them. The first was a video game app, and the second was a writing app. I had friends/acquaintances I could use to conduct real user research on both topics. These two topics were passion projects, and my ability to research with friends of friends helped my interview skills.

3. I joined a few different hackathons to see what it was like working with other people (and the networking was great). For one hackathon, I was able to work with a product manager, product marketing manager, UX designer, and developer. Although we didn’t win the hackathon, I felt to a degree what it was like to work in a tech company for that entire weekend.

4. I offered to do small freelance projects for friends and family. I also asked my network if anyone needed help on projects. With this, I was able to work on three small projects for others. I only added one of them to my portfolio because of the size, but it was nice to have the potential to talk about multiple projects.

With all of this work, I created a portfolio of a few different studies. I felt good about my portfolio. Was the portfolio perfect? No. Did it include everything a portfolio should consist of? No. Everyone starts somewhere. But I had case studies. I had something to present and talk about during my interviews.

Are you trying to break into user research?

These are the steps I encourage you to go through:

- Find a non-profit, charity, or something similar that you can create a project around. You don’t need to know any contacts at the given organization, nor do you have to tell them you are researching their website/app/platform. You can always send them any recommendations after you are done and see what happens!

- Volunteer for a local small business or organization to see if you can help them. I went to a few different local shops in New York City to see if they needed user research help. I had a few leads on this but, ultimately, spent my time on the non-profit organizations. Due to COVID, here is an alternative: You can also find Facebook groups on specific topics and reach out to people via Facebook or LinkedIn.

- Pick a true passion project and create a case study around this topic.

- Join hackathons (even virtual) to experience working with others you would work with as a user researcher.

- Reach out to friends/family, and friends of friends/family to see if you can volunteer your time to research their websites/apps/platforms.

These are actionable steps you can take to get more experience in user research before your first role, or even between roles!

If you’re looking for some guidance on creating a case study, check out my user research case study outline freebie.

—

Interested in all things user research? Sign up to my newsletter and join the slack community! And check out User Research Academy for freebies, courses, and more!

I sat down with a bunch of product managers for a conversation

And the questions I received were fascinating.

The other day I was invited to an informal product meetup as an informal speaker. My fiancé (yes, we got engaged!) is a product manager in Berlin, and he meets about once a month with a group of about ten other product managers. They swap stories and experiences, discuss tools, and seek advice from one another on all things product management. I, personally, imagined meetings filled with JIRA talk and phrases like, “it depends…”

The other day I was invited to an informal product meetup as an informal speaker. My fiancé (yes, we got engaged!) is a product manager in Berlin, and he meets about once a month with a group of about ten other product managers. They swap stories and experiences, discuss tools, and seek advice from one another on all things product management. I, personally, imagined meetings filled with JIRA talk and phrases like, “it depends…”

A few weeks ago he asked me if I would like to come in and talk with the group about user research. He asked me if I’d be willing to answer as many questions as possible and be an open book about user research during those two hours. I said yes, but I was a bit apprehensive. A group of ten product managers and one user researcher.

I was mostly nervous that I would be unable to answer their questions well and that I would give them the impression that user research was not valuable. Imposter syndrome crept in on the day of, but I swatted it away. As researchers, we can struggle so much with defending and explaining our craft. I didn’t want to leave a bad impression or mistakenly convince people that user research is unnecessary.

We arrived at the apartment. Cheese and wine were served as everyone settled into their seats. Soon, heads turned to me. Someone asked me if I prepared anything (spoiler: I hadn’t). I explained that I wanted this to be an open forum for them to ask any questions they wanted to and I would do my best to answer.

It was over two and a half hours later that we noticed the time.

What questions did I get?

I had quite a lot of questions from the product managers:

- When do I reach out for help on user research?

- When should I hire a user researcher?

- What should I look for when hiring a user researcher?

- How do I pitch hiring a user researcher to the company?

- What should I expect from a user researcher?

- How should I work with a user researcher?

- Should a user researcher know how to do both qualitative and quantitative data?

- How should I get started with some user research (if I don’t have a researcher our the team)?

- How should I pitch the value of user research to a company/organization?

- What questions should I ask a user researcher?

What surprised me?

There is bad user research conducted out there. Just like in any profession, it can go wrong, and this can leave a bad taste in people’s mouths. A few product managers brought up some difficult times they experienced with researchers. I am sure you can think of some tough situations with product managers as well.

Things can go wrong in all professions and you can have less than ideal interactions with anyone. However, user research is still relatively new as a profession and a role. We have had to push for user research to be done, constantly pitch the value of user research, and defend the validity/reliability.

Based on these experiences, product managers were curious about what user researchers could do that they couldn’t. When they’ve seen user research done badly, they think, what is the point of a user researcher?

Other topics that surprised me:

- Product managers want to work with us.

- Product managers don’t necessarily know how to approach us. They deal a lot more with business problems versus customer problems. As researchers, we need to help our stakeholders translate the business into customer-centric thoughts

- We don’t have enough open communication with product managers. We can’t take these questions too personally. If product managers don’t see the value in user research, it is much more helpful they are honest and ask us, rather than just thinking this to themselves. If we are willing to hear the hard questions and give meaningful answers, we can educate in a positive way

- We have a lot more in common than we think. Product managers and user researchers want the business to succeed — we both want to solve problems and create a positive impact. If we work together better, we can do this much more effectively and efficiently.

What is next?

I left the meeting buzzing, despite drinking water all night and abstaining from the wine (I wanted my mind to be sharp). I wondered to myself, why don’t we have these open and honest communications more often?

We constantly work with product managers, among many other stakeholders, all the time, but we don’t seem to have much open communication. My biggest takeaway is this:

Speak with product managers as if they were your users, stakeholders, and peers. Be open to their questions (even if they hurt), and be honest and kind with your responses. Educate and learn. Together, we can truly work so well.

Here are some additional action items I will take away from this:

- Meet more often with product managers — I am going to try to get back into the group as a follow-up but, aside from that, I will start attending product management conferences, webinars, and meetups to better understand them

- Take these questions and write down answers for my stakeholders, so they can easily reference them. For example, the “when should I reach out” question can be answered in a Google Slides presentation that stakeholders can later reference!

- Writing an article about user research geared toward product managers that answers these questions, and has additional tips

Take some time to sit down and chat with your product managers. Let them as you the hard questions and give you feedback. We can continue to educate each other and work as a team.

The life and timelines of research projects

When I was first starting as a user researcher, I had no basis of understanding how projects worked in tech companies. The only mental model I had of research was academia. I was unable to find examples of research projects online and had no idea how they worked. Eventually, I learned that once I saw research in action. However, it would have been highly beneficial for me to understand the overall process beforehand.

When I was first starting as a user researcher, I had no basis of understanding how projects worked in tech companies. The only mental model I had of research was academia. I was unable to find examples of research projects online and had no idea how they worked. Eventually, I learned that once I saw research in action. However, it would have been highly beneficial for me to understand the overall process beforehand.

For those who have not yet worked in a tech or product company, it can be hard to envision what projects would look like. Previously, I wrote an article about a week in the life of a user researcher. With this article, however, I will shine some light on a seemingly mysterious process only available behind closed doors.

Let’s begin

Imagine you are working at Best Friends Animal Society, an animal welfare organization in America dedicated to ending companion animal deaths in shelters.

Sidenote: if you have a chance to volunteer there, I highly recommend it!

Second sidenote: tears came while writing this article due to my absolute love for animals. If you are looking to do a portfolio piece, consider volunteering for a charity or non-profit organization!

You are a user researcher at this organization. You work with different departments, but primarily tech, product, and marketing. You are continually working with product managers, UX designers, and developers to empower teams to make the best decisions for the organization.

Usually, your research projects come to you in two different ways:

- From precious research insights

- From an internal stakeholder

For this project, we will focus on the second. A research project lands on your desk from one of the product managers. Recently, we have seen a drop in the usage of the “adopt” area of the website. The product manager looked at Google Analytics and saw a considerable decrease in time on page and click-thru rate. The team in charge of that functionality wants to understand what is going wrong.

What would you do?

The life of a research project

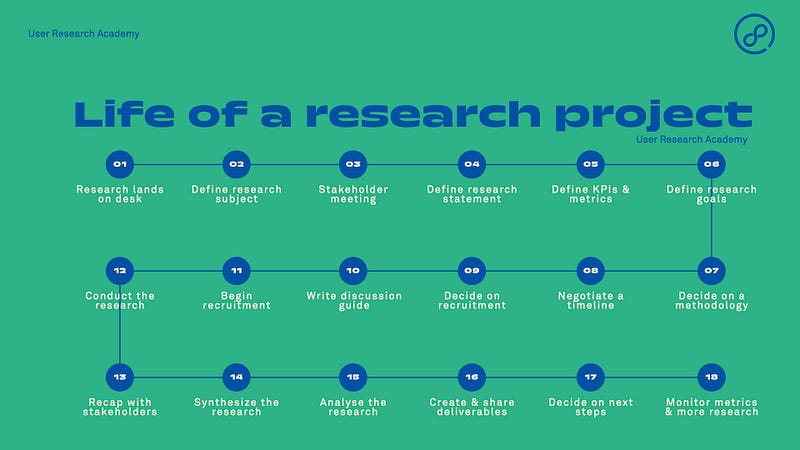

Before we dive into the timelines with this project, it is essential to look at the holistic life of a typical user research project.

I want to stress that this is a typical journey and research won’t always happen in such a linear (and clean) fashion. Often, you have to skip straight to recruitment because of timelines or conduct research while recruiting. This overview is simplified but gets the overarching message across of the steps a researcher generally takes during a project.

As you can see, before you jump right into research, you go through the steps of really understanding and defining the problem and goals of the study. You are meeting with stakeholders to ensure alignment and answer clarifying questions.

Arguably, steps 1–6 are the most important as they drive the project in a particular direction. For example, the research statement and goals help define the methodology, recruitment, and the discussion guide. This building block effect is why it is vital to take these steps before diving into research.

For the ease of this article, let’s come to some conclusions:

Research statement:

- We want to better understand the user’s mental models when it comes to animal adoption to improve our current website

Research goals:

- Understand how users are thinking about adoption, in general

- Uncover how users are currently interacting with the adoption feature on our website

- Identify pain points in the adoption process, in general, and on our website

- Discover other apps/websites users are interacting with to adopt animals and their experience with them

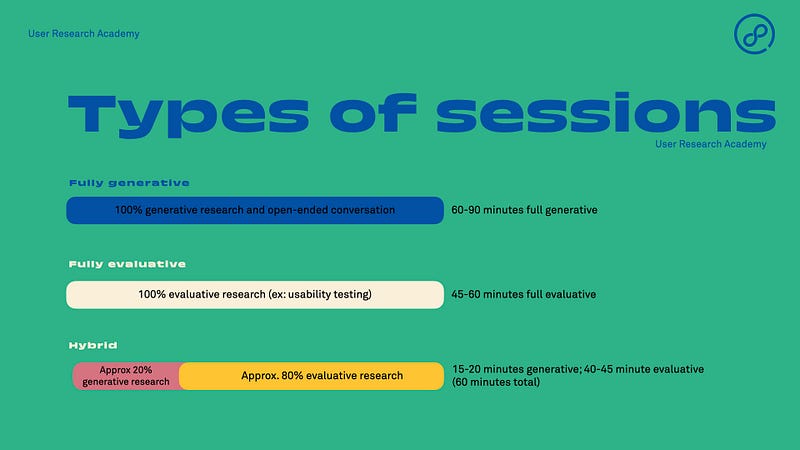

Now comes the picking of methodologies. I have previously written on this subject, and it is a difficult one to explain. However, you use your goals to help guide you to the write methodology, which lands in one of three buckets:

- Purely generative research

- Purely evaluative research

- A hybrid between generative & evaluative research

Here is a high-level and simplified process I go through when deciding:

- Are we looking to understand mental models, frustrations with current methods, or how users think about concepts in general? Are we looking agnostic of our product? -> Generative research

- Are we trying to evaluate how users are interacting with a prototype or live product? Are we looking to see pain points associated with our particular product? -> Evaluative research

- Is there a mix of both? -> Hybrid research

Once I place the goals into one of these three buckets, I can decide on the methodologies that would help answer these goals. The most common associations are:

Generative research

- 1x1 in-depth discussions (aka interviews)

- Contextual inquiry

- Mental models

- Customer journey interviewing

- JTBD

Evaluative research

- Usability testing

- A/B testing

- Competitive testing or analysis

- Benchmarking

- Surveys

Hybrid

- 1x1 in-depth discussion + usability testing

- Card sorting

- 1x1 in-depth discussion + follow-up survey

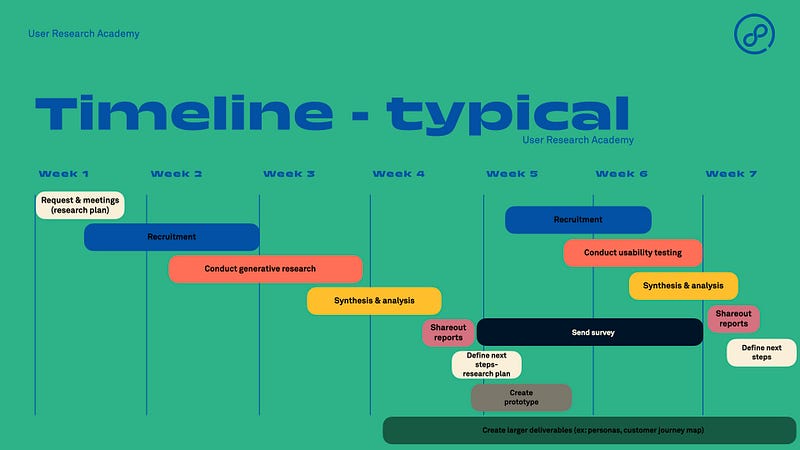

Timeline of a typical project

The timeline of a typical project can be over three to six weeks. As mentioned above, it can include just generative research (which is about four weeks total) or just usability testing (which is about three weeks). Another standard timeline is conducting generative research to understand the problem, and then creating insight-based prototypes to usability test.

As you can see, in the above image, you decided to run two separate studies. First, you run a 1x1 in-depth discussion to understand the following goals:

- Understand how users are thinking about adoption, in general

- Identify pain points in the adoption process, in general

After, you run a usability test to cover the following goals:

- Uncover how users are currently interacting with the adoption feature on our website

- Identify pain points in the adoption process on our website

- Discover other apps/websites users are interacting with to adopt animals and their experience with them

In this evaluative study, you may also offer prototypes for users to test in addition to looking at the current live product. Or, you may have to run a separate evaluative study to test those prototypes.

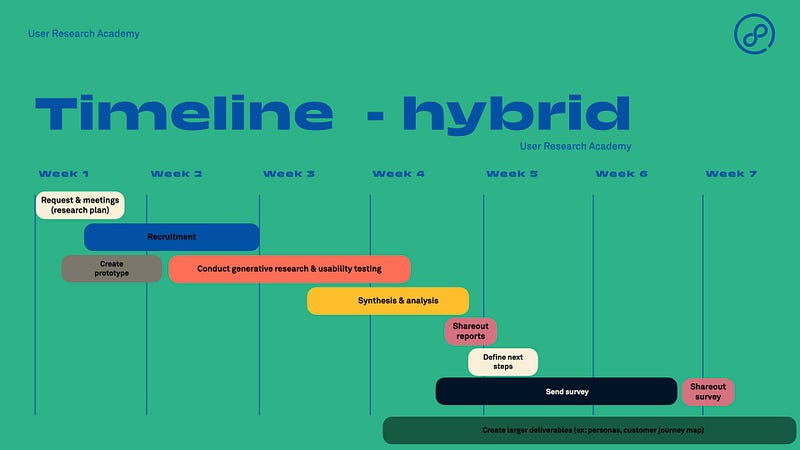

Timeline of a hybrid project

Slightly different from a typical project is the hybrid project. I love hybrid projects; they are my absolute favorite types of studies to run. I feel like I get much more accomplished in each session than with the typical project timeline. I also use hybrid projects to highlight the importance of generative research.

In this instance, you run a more extensive study, including generative and evaluative research. In one session, you are conducting a 1x1 in-depth discussion followed by a usability test. In this study, you can answer the following goals:

- Understand how users are thinking about adoption, in general

- Uncover how users are currently interacting with the adoption feature on our website

- Identify pain points in the adoption process, in general, and on our website

- Discover other apps/websites users are interacting with to adopt animals and their experience with them

While I prefer hybrid projects, they are more advanced than the typical approach where you tackle one method. Hybrid projects take more careful planning and time management. While you are practicing and honing your craft, I recommend starting with a regular timeline and making your way to hybrid.

These timelines are not rules!

As I mentioned, these steps and timelines are ideal. You may have to do lean research in two weeks, or you might not have the budget to run two or three separate studies. In this case, you will have to choose between generative and evaluative research. Additionally, you may already have previous research the team could look into to answer the questions.

I offer these graphs and steps as guidance towards your next research project. They are not hard and fast rules to live by, and I encourage you to find the best process for yourself and your organization.

If you’re interested in joining an awesome community of user researchers, join the User Research Academy Slack. If this article piqued your interest, and you would like to learn more, check out the courses and webinars I offer.

How to interview as a user researcher if you aren’t (yet) a user researcher

When 1–3 years of experience is necessary for an internship

A company’s expectations of user researchers are high. It is a competitive world out there, especially for people looking to break into the user research field. My heart sinks when I view intern or junior positions that require experience (stop doing this!) or act as though applicants should already be experts. While I believe we need to revamp our hiring process, this is the current situation.

A company’s expectations of user researchers are high. It is a competitive world out there, especially for people looking to break into the user research field. My heart sinks when I view intern or junior positions that require experience (stop doing this!) or act as though applicants should already be experts. While I believe we need to revamp our hiring process, this is the current situation.

I get so many questions from people trying to understand how to navigate what should be a simple interview process. Let me tell you. It is not easy. How are you supposed to have real-life experience and know everything as an intern or junior level? I have been in this field for over seven years and am still learning.

What I can offer are a few steps and pieces of advice to feel more prepared for your first user research interview. They won’t answer all the questions, but they might make you feel better walking into the session.

Have a story in mind

My first and most significant piece of advice is to have a story in mind before starting the session. This story should be an example of a project you completed. You want to have this story to help you answer the questions they will ask you. Ideally, in this story, you will have faced challenges and can reflect on what you would improve next time.

A great way to understand how to create a story is to look at other researcher’s portfolios. These portfolios will help you know how researchers work in a company.

Before I started working as a user researcher, I knew I had to create a portfolio piece. With this in mind, I volunteered to understand animal adoption and how people interact with animal rescue websites. I chose a company I volunteered with in the past. I conducted generative research to understand pet adoption in general and usability testing of the website. I also did a card sorting exercise to see the impact on navigation. I brainstormed some metrics I imagined the company would be tracking, such as click-through rate, in-person visit rate, contact rate, etc. Although I didn’t have access to their data, I wanted to show my understanding of business metrics.

I then used this story throughout my interviews as an intern and junior researcher. This story helped form my process and, although it was outside of a typical company, I had answers to why I chose the methods, how I recruited, and how I conducted the research. I also prepared reflections and challenges:

- Working alone is very difficult, and I was lucky to get some input from my friends who are designers

- I developed a report with findings to pitch to the company, but ultimately, did not have the opportunity to work with them

- I wasn’t working on a strict timeline, but I tried to simulate the timeframe in a company setting (I allocated five weeks for the entire project)

Understand how the company works (and company jargon)

It is challenging to demonstrate how you would fit into a team without a general understanding of the basics of how tech teams work. And without the jargon or terminologies that are common in the tech and user research industries. I recommend researching how tech teams work, how businesses work, and how user research can fit into organizations. This will make you stand out to recruiters and companies, as someone with a real passion and motivation to go above and beyond.

When I was newly interviewing, I found it very important to understand the timelines at a company. I delved into understanding how scrum, sprints, and agile worked since the majority of companies I applied to used those methods.

I read everything I could about how user research might work in these confines. I also learned about how long specific user research methods generally take. Although timelines can differ (through recruitment availability and tools the company has), here are the basic guidelines:

- Generative research methods can take 4–6 weeks

- Evaluative research methods (usability testing) can take 2–4 weeks

- Surveys can take 1–2 weeks

- Recruitment can take 1–2 weeks

- Alignment meetings can take up to 1 week

Some of these methods can overlap, but keep these in mind when determining a timeline. As a note, you can start researching before you finish recruiting to cut down timelines!

With this in mind, I tried my best to simulate how I would research projects at a company. When people asked me how I would deal with tight deadlines, I had mentioned my ideas on methods I could overlap and ways to speed up recruitment.

I wrote an article on the essential concepts, processes, and jargon to understand. Check it out here.

Know who you will work with and how you can collaborate

Understand the different roles you will work with. Some of the most common for a user researcher are:

- Product managers

- Designers

- Developers

- Marketing

- Account management

- Customer support

It is helpful if you have never worked in a typical company setting to research each of these roles. Understanding their day-to-day and their goals will help you know how you would work with them.

Let’s go back to the example I used above. I had never worked in a tech company. I had no idea what a product manager was.

Knowing the roles I was going to be working with, I could answer questions about when I would engage with them. I also felt more confident about how I would pitch user research value to these roles since I could speak to the goals they were trying to accomplish.

For example, even though I had never researched content copy, I knew that was something marketing worked on. That way, I could talk about how I might interact and help the marketing department. Additionally, I knew customer support had incoming calls about customer problems. I could then talk about how important it was for me to meet with them regularly to understand top issues, which would reduce their workload if fixed.

If you aren’t able to talk to the different people in these roles, look up job descriptions. These descriptions should help you understand what the responsibilities are and what they are trying to achieve.

Be prepared for a whiteboarding challenge

The whiteboard challenge for a user researcher can be a daunting task.

Your interviewers will give you a vague prompt and want you to provide them with an idea of your process. This exercise allows them to evaluate how you go about approaching a problem in a “real-life” setting, beyond your curated portfolio. Companies are increasingly valuing employees’ thought processes over their qualifications.

Understandably, this can be a challenging experience, which is why you should practice beforehand! Whiteboarding your approach is a great skill to have in general.

Check out my whiteboarding approach in this article. And practice!

Get ready to answer tough questions

There will be some questions that you might not be able to answer. Keep in mind, it is okay to say, “I don’t know.”

A lot of your answers will be hypotheticals. For instance, since I didn’t work with product managers in the past, I could only say how I might engage with them. By knowing the different roles, you can better hypothesize what you would do in various situations.

When I had to talk about how I would work with product managers, I answered based on my research. I knew I would have to involve them early, that I might have to explain the value of user research, that I would have to meet with them frequently to ensure user research was correctly involved. With this knowledge, I brainstormed ideas on how to answer those questions. I read articles on how people have tackled these issues in the past and used that as my hypothetical answer.

Here are some questions you should be prepared to answer:

- What is your user research process?

- How do you manage difficult stakeholders?

- How do you convince stakeholders about the value/importance of user research?

- If you had X goal, which methodology would you choose?

- How do you select the right method for a project?

- How do you turn insights into actions a team can take?

- How do you ensure your deliverables are acted upon?

- Talk about a challenge you have faced. What was it, and how did you overcome it?

- What is the most challenging part of your research process? (For you and others)

The best approach for interviewing for a user research position is preparation. Take your time in understanding how user research works at companies, and think about how you would positively impact that organization through user research. If you are feeling stuck, read through another researcher’s portfolio or ask a fellow researcher to talk you through their process.

Torch the user research reports

Creative ways to share user research insights

The first time I was asked to create a research report, I was lost. After spending my life writing academic reports, I was used to the long-winded, endless vocabulary in these presentations. Producing a report like that, as a user researcher, would prompt a lot of blank stares. And when I tried it, it did. After (many) failed attempts, I have finally found three ways to effectively share user research that is tangible, creative, and realistic for a user research team of one or fifty.

The first time I was asked to create a research report, I was lost. After spending my life writing academic reports, I was used to the long-winded, endless vocabulary in these presentations. Producing a report like that, as a user researcher, would prompt a lot of blank stares. And when I tried it, it did. After (many) failed attempts, I have finally found three ways to effectively share user research that is tangible, creative, and realistic for a user research team of one or fifty.

After creating and presenting my first user research report, I received many blank stares. I stood in front of the CEO, CTO, and head of product — shuffling through a pretty dull, and visually unappealing, deck. (To my humiliation, I’d used a preset gradient background). Each slide was filled with information I gathered from research sessions. And while it was helpful information, it was a lot. It wasn’t distilled down into anything digestible by upper-management.

That was when I learned my first lesson in presenting research: It doesn’t matter how useful the findings are if you aren’t able to communicate them effectively with your team. I also realized how easy it was to feel like an imposter in this field.

The worst thing you can do when you present research or create a research report is to have it sit in a folder somewhere, collecting dust. Insights need to be infused with excitement and urgency to promote action, and it is our job, as researchers, to do just that.

Now, whenever I share user research, I use the following formula:

Informative + actionable + fun = solid user research shareout

After many attempts at successfully sharing user research in an energetic and knowledgable, I have finally found five ways to effectively share user research that are tangible, creative, and realistic for a user research team of one or fifty.

Different ways to share insights

Demo desk: A “Demo Desk” is an area that allows employees to stop by and play with the current prototypes/ideas you are working on and give feedback. This will give other employees the chance to understand what the product team is working on and also give their input to impact your ideas. It is a great way to understand what user research is, how it is conducted, and how it affects your product/service.

Usability movie night: Usability movie night is an event you can host showing back-to-back video clips of usability tests, which brings everyone closer to the customers’ experience. Nothing makes us empathize with our customers more than watching them use our product. Whether they’re struggling to understand the UI, or they’re thrilled to interact with a new feature, observing the customer experience first hand is incredibly eye-opening. It helps teams plan where they should next focus their efforts.

Choose Your Own Adventure: The entire point of a CYOA is to bring someone through a story in a way that they feel very connected to the material. I have used CYOA to connect the product and tech teams to our users in a creative and digestible way. I craft stories and scenarios for our personas and allow the teams to make their way through these stories that reflect actual choices users must make. Shopify wrote about how they have had much success with this type of deliverable.

Research session snapshots: This type of summary I use is full of factual information and consists of direct recommendations or the next steps. I create a research session snapshot after a usability test, or when I am synthesizing a few generative research sessions for a team. Generally, in this scenario, we might not have time for a group synthesis session, or this could be a summary of the group synthesis session.

Canva infographics: Qualitative research summaries and reports can get very word-heavy. By breaking the words into infographics, we give a visual representation of what we learned, which is more engaging for those receiving our reports.

How to use these methods

Now that I have explained some of the different techniques I use to share user research insights and ideas, I will take you through how I set each of them up.

Demo desk

Necessary equipment includes iOS and Android test devices, Windows test device, Mac test device, desk area, feedback sheets, candy (for a reward!)

- Find a central space in your office space where you have space to set up the various test devices relevant to your product/service

- Speak with the designer(s) to understand any upcoming prototypes or concepts they want to test. The feedback you can generally expect from a demo desk is visual appeal, usability, typos, missing information, confusing information, and what is going well

- Set up the prototypes of the test devices

- Write up brief descriptions of each prototype, so people are aware of the context and a feedback sheet.

- These are the steps I use to explain:

- Choose your preferred device

- Open up the prototype (all the current ones will be on the homepage/desktop)

- Read the brief context about the prototype you choose to test

- Be aware, it is a prototype, so things might not work as they do on our platform

- Play around with the prototype for 10–15 minutes (more is even better!)

- Fill out a feedback form

- Leave your feedback form in the demo desk feedback jar

- Take a piece of candy and have a wonderful day

- If you are having any trouble, come to Nikki’s desk and annoy her until she fixes it 😊

6. Write up a feedback sheet. Here is what I include:

- Date and prototype being tested

- What was confusing about this prototype/idea?

- What didn’t work?

- What was missing?

- What would you change to improve it (and a short answer on why)

- What was working well?

- What did you like about this prototype/idea?

- Any other feedback, comments, questions, or suggestions

7. Aggregate the input every week (or few days) and present to the designer(s)

Usability movie night:

- Choose a theme for the night, such as a pattern you have seen in generative research, or a series of usability tests on a particular prototype

- Create an introduction to the movie night, which gives the audience a context of the goal and objectives behind the research you were conducting

- Find short and compelling video clips (you can do this while you synthesize) that clearly show user issues, confusion, unmet needs, or goals they are not able to achieve. I usually pull about 7–10 video clips, two minutes each. Put these together in succession to show the pain points or problems users were having. I also include two or three short clips at the end of positive remarks users had about the product/service.

- Engage the audience in a game after they view the videos. This could be a role-playing game where people write down ideas on how to alleviate these pain points, and the top three ideas win a prize. Or, you could set up a scavenger hunt around the office, in which the clues correlate to problems or pain points the users had.

- Order snacks, pizza, and beer for the team for the usability night and have fun!

Choose your own adventure.

This is an excerpt from an article I wrote for dscout, which gives more information on the CYOA model. As mentioned, Shopify also went into detail about how they create CYOA.

- Choose a problem you want to bring to light. For instance, I wanted to highlight the non-linear path that comes with planning travel and all the nuances involved. This will give you a good understanding of the type of story you want to create, and which part of the journey to focus on. I always ask myself: What is the goal of the user at this point? Where does that goal start and end? I now have a story starting point and endpoint and need to include the details in between. I then choose the most common pain points, needs, and tasks to include in the story.

- Create a user flow. Once I had an idea of the overarching story, I broke it down into a flow or journey the user experiences. Mostly, these are steps the user has to go through to achieve that goal identified above. At this point, most of these are linear, task-based steps, without any emotion. It’s okay if they are a little disjointed, and some parts don’t connect correctly with others. This stage is really for outlining the basic story.

- Infuse emotion. Once I have a basic outline of the story, I begin to add emotions to the context. Instead of simple text, I form scenarios. For instance, “select a date to travel” becomes “Jonas isn’t sure which exact dates he will travel. On the website, he sees the option to select a set date range, which annoys him, seeing as he wants to explore several different options.” Adding these intricacies allows readers to understand pain points in a way that is not solution-oriented and is product-agnostic.

- Add choice. Now comes the most complicated, but interesting, part: adding options. This is where it is very beneficial to get into the mindset of the user and relive the research sessions. Where do your users have to make decisions? What are the triggers that cause them to think: “Forget this website/app, I’m going somewhere else”?

- Read your story. Go through the CYOA, ensuring it makes sense, and you have included the different possibilities in an easy-to-understand narrative. The value of a CYOA is that it can continuously evolve and grow as you learn more about your users.

- Send it out. I first send these stories to the UX team, so they can glance over to see if everything makes sense. I then roll it out to the broader company. Often these stories are based on personas, so I also make sure to socialize those with the story to give more context.

Research session snapshots

These snapshots are a quick way for the team to easily visualize what important information has come from the research sessions. My snapshots include:

- Which participants faced this issue (ex: P1, P4, P5, P7)

- The insight/problem

- The actions/recommendations

- A quote

- 1–2 video relevant video clips that highlight the issue

- If it is a usability test, an annotation of the screen and what happened

I hope these help diversify the way you share your research insights and give you some creative ideas. Remember: food and drinks really help to motivate people to join events — so keep that in mind. Please let me know if and how you use these, and any adaptations you do!

If you are interested, check out more free content and my offerings on www.userresearchacademy.com and join our slack channel

How to ask for feedback

And why it is so important.

No matter where you are in your life and your career, there will come a time where you will either ask for feedback from someone, or you will be asked to give feedback. Feedback is an amazing tool and is one of the best ways you can learn from others. Without continuous feedback, it is almost impossible to improve.

No matter where you are in your life and your career, there will come a time where you will either ask for feedback from someone, or you will be asked to give feedback. Feedback is an amazing tool and is one of the best ways you can learn from others. Without continuous feedback, it is almost impossible to improve.

Learning how to properly ask for feedback, and how to give feedback, are two huge milestones in your career. By asking for feedback, you admit you don’t always have the correct or best answer, and you open yourself up to a world of opportunities. You show people that you aren’t afraid to be wrong, and you also show yourself that it is okay to ask questions. And, by giving feedback, you help others grow personally and professionally.

Without asking for and giving feedback, how would you be able to move forward? How would you know ways you can improve for next time? Albert Einstein was attributed (although many would argue otherwise) with saying:

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

Without feedback, we would continue doing the same thing over and over again, hoping for a better result. Continuous feedback breaks these toxic cycles.

However, this can go horribly wrong. On both sides.

Let’s start with the concept of asking for feedback…

It is wonderful when people ask for feedback. I absolutely love it. However, sometimes, the questions can miss the mark. I believe the right intent is there, but it can leave the person receiving these requests either frustrated, confused, or tired.

For example, I spoke with a few friends who get asked feedback frequently for portfolios, resumes, jobs, etc. Both of the below scenarios are, of course, exaggerated to get the point across, but they are still representative. Here are three examples:

**I do understand we are in a time where people may really need jobs, and we are emotionally exhausted. So if you receive a message such as the below, be kind and try to explain that you simply need more information to give the best feedback/do the best networking possible

Example 1 (networking):

- Person: “Hey, can you help me find a job?”

- Feedback giver: “Hey, let’s see if I can help. Can you tell me more?”

- Person: “I’d like a job in user research.”

- Feedback giver: “Okay…where are you looking for a job.

- Person: “Anywhere, I can work remotely or move.”

- Feedback giver: “okay…where are you currently located?”

- Person: “Boston.”

- Feedback giver: “And what kind of role are you looking for? What level? What type of company…”

- Person: “Anything user research related.”

Example 2 (networking):

- Person: “Hey, can you give me some feedback on my portfolio piece/resume?”

- Feedback giver: “I’d be happy to, what kind of feedback are you looking for?”

- Person: “If it is good and if it will get me a job.”

- Feedback giver: “Sure, but what is your experience level”

- Person: “Mid-level.”

- Feedback giver: “Okay, and what types of jobs are you applying to? This will help me with giving you the best feedback.”

- Person: “Mid-level user research jobs.”

- Feedback giver: “Can you give me an example of a company?”

- Person: “UK Gov.”

- Feedback giver: “Okay, and what is your biggest strength and your biggest weakness in your portfolio?”

- Person: “I don’t know.”

The thing is, we are all learning how to network and how to get through these situations. Some people have been networking for years, and some people are naturally good at it. But others are still trying to navigate the digital world of networking and asking for feedback, where we lose important indicators such as body language and tone.

Example 3 (workplace, over slack):

- Researcher: “What do you think of this research report I just put together?”

- Colleague: “It’s nice…but I am not really sure how to use it…”

- Researcher: “What do you mean, you don’t know how to use it?”

- Colleague: “Maybe it is just me, but how should I use this for roadmap or planning?”

- Researcher: “Well, it isn’t as if I can give you all the answers, but it shows the number of participants who were confused on slide 7.”

- Colleague: “Sure, I guess I’m just not sure what the next steps should be. Really, maybe it is just because I’m not used to working with a researcher!”

- Researcher: “Okay, then what can I do?”

- Colleague: “Maybe you could put the next steps or recommendations you have…”

- Researcher: “Okay, sure.”

It can be difficult to hear negative things about work we’ve put time and effort into. Sometimes the feedback will come out in kinder ways (such as above), and sometimes not. We have to learn how to take this feedback and make it as constructive as possible, to learn how to do better next time.

Some guidelines on asking for feedback:

- Think about both sides. The best advice I can give when asking for feedback is to think critically about your message. Would you like to receive it? If you received it from someone else, could you help them?

- Mean it. Don’t ask for feedback if you aren’t going to use it or are just going to defend whatever you currently have or are doing. This isn’t helpful for anyone. It is totally fine to disagree and have discussions (that is another way we learn), but don’t just ask and ignore.

- Give more context. As mentioned above, more context makes communication more clear for everyone. It also makes everyone’s job a lot easier. It is really difficult to authentically reach out to help someone find a job if you aren’t feeling motivated to do so based on the message you received.

- Try not to get defensive. As I mentioned, it can be hard to not get upset when someone doesn’t understand something you have worked on. Remember, you are all working together towards the same goal within a company. The best thing you can do is understand someone’s perspective and then decide what to do with the feedback. Maybe there is a misunderstanding and you can make things more clear, or maybe something is confusing that you can change.

- TALK to the person first. If you are connecting with someone you don’t know and asking them for feedback, create some conversation. Show them you did some research and why you want to get their feedback. Maybe they wrote an article or gave a talk you loved — let them know! Try not to just lead with asking for things.

- Give people the benefit of the doubt

Better feedback conversation examples:

I just quickly wanted to give some good examples that are similar to the ones above. These are also based on real-life experience! It just takes time to learn these skills, but it is important in advancing your career.

Example 1:

- Person: “Hey! I was wondering if you could help me with finding any opportunities. I am a mid-level user researcher located in Boston, MA (but willing to relocate or work remotely). I have worked as a researcher for 3 years, mostly at B2C companies. I am looking to move to a smaller sized company (under 500 people) and in the B2C space. I would love a role in education tech or medical tech, however, I am also happy to work in the e-commerce space (where I have more experience). I’ve attached my resume if you want more details. Please let me know if there is anything else you need from my side. Thank you!”

Example 2:

- Person: “Hi! I am currently looking for a new job in user research. I created this portfolio based on my recent work at a B2C company. I am starting to apply to some junior and mid-level roles (I’ve only been in the field for about 1 year). I am really struggling with the layout and making sure my content is engaging. I have some nice deliverables, but I’m not sure if everything makes sense when I put it together. Would you mind looking through it to see if it tells a story? And also if there is any content I am missing that you think would be applicable to a hiring manger? Thank you and let me know if there is anything else you need!”

Example 3:

- Researcher: “What do you think of the research report I sent you a few days ago?”

- Colleague: “Oh, it’s nice, but I’m not really sure how to use it…”

- Researcher: “That is such great feedback, thank you for sharing. Can you tell me more about what is confusing or missing? I’d love to make it more actionable for you, and be able to improve the next reports! Maybe we could have a meeting to discuss it?”

All of these are just simply models based on some experience I and others have had. These aren’t rules, by any means, they are simply some guidelines you can use when thinking about asking for feedback. Again, I’m not saying the first examples are wrong, but they might come off as difficult to engage with to some. Remember, you are asking favors of people when you ask for feedback. You want to make sure you come off as clear and understanding.

We all can come together and think about how our words impact each other, on both sides, and become better at communication. As the world evolves, online communication will start becoming more and more inherent in our lives. It is best to think about having a conversation online as you might in person.

Stay safe and healthy

For more engaging discussion, please sign up for the User Research Academy slack group! And check out User Research Academy for free resources.

Seven steps to writing a screener survey

How to make sure you are always getting the best participants.

Screener surveys are an excellent tool for the beginning of each research study. Before you jump into recruiting, you can send out this survey to assess potential participant’s backgrounds, behaviors, habits, and other essential characteristics.

Screener surveys are an excellent tool for the beginning of each research study. Before you jump into recruiting, you can send out this survey to assess potential participant’s backgrounds, behaviors, habits, and other essential characteristics.

There are a few reasons we write screener surveys:

- Find and talk to the most relevant participants for your research study

- They help you guarantee you are getting high-value participants

- Ensure return on investment for your research will be as high as possible

- Avoid wasting time/money on suboptimal participants

- Avoid wasting the time of others (ex: users who might not be the best fit)

- Dodge awkward research sessions where the participant cannot meaningfully answer the questions you are asking

I learned about the importance of screener surveys the hard way: through first-hand awkward experiences with the wrong participants for my study. I was researching the process that occurs when people move to a new home or apartment. I wrote my screener survey, which was full of demographic information, and asking a few questions about whether they had moved recently.

We received a good number of responses quickly, and I was happy. They were matching the demographic data we wanted from our target participants. Nothing ticked in my head, saying, “how are we getting so many participants so quickly?” Not to spoil the plot, but it had to do with the screener survey. It was too focused on demographic data and not focused enough on behavior.

So, what happened? I had participants come in, and I asked them my default starting question, “tell me about the last time you moved.” They gave me an overview, and I set to dig into the details:

- Me: “Okay, great, now walk me through the step-by-step process you went through.”

- Participant: “Oh, I wasn’t involved in the process. My partner/real estate agent took care of that. You should probably talk to them.”

- Me (internally): Sh*t.

Some of the people had lied on the screener survey. They responded saying they had moved in the past year. However, some had moved a few years ago. But they knew what I was looking for and the correct answer to participate for the incentive.

I had recruited the wrong participants because of my screener survey. Not all the participants were a bad fit, but an overwhelming majority ended up not being super helpful. I had to redo my screener survey and start recruiting again. That is when I learned, screener surveys:

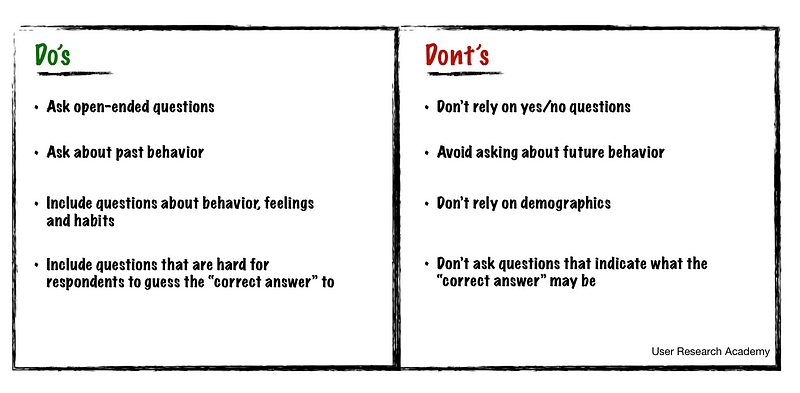

- Are not all about demographics

- Should focus on behavior and habits

- Need to elicit specific information

- Can’t give away which answer is correct

After that experience, I took my screener surveys much more seriously and learned how to write them correctly.

However, they can be tricky to write

Like most things in user research, we have to consider how we construct screener surveys seriously. Certain questions can backfire on us. You have to achieve a balance within a screener survey:

- Get the right information to qualify the best participants

- Make sure you are not asking obvious questions that would lead people to exaggerate their responses to participate

After a few years, I have done my best to achieve this balance. I always use the following steps before writing and sending out a screener survey.

The seven steps to writing an excellent screener survey

1. List the criteria of your ideal participants. Before you even think about recruiting, it is beneficial to list out all of the different criteria an exemplary participant would have. And think about the information you need from them. For instance, if I had genuinely thought about needing information on the step-by-step moving process, I would have (hopefully) included questions about whether or not they took part in this. It is beneficial to consider:

- Who are your target personas or proto-personas

- What behaviors do you want to understand more?

- What habits are you trying to target?

- What are the goals the user is trying to accomplish?

2. Write one question for each criterion you identified

- For each ideal standard/behavior, write one screener question

For example, if it is essential someone has wanted to move for 60 days; write a question about this behavior

- Make sure to write precise questions that ask for particular behavior patterns or timeframes:

Imprecise criteria: People who have wanted to move for 60 days

Precise criteria: People who have visited 3+ apartments in the past 60 days

3. Focus on how potential participants feel and HAVE behaved

- Focus on their past behavior, as it is the best predictor of future behavior

Future question: Will you look at apartments in the next 60 days?

Past question: Have you looked at 3+ apartments in the past 60 days?

- Ask for only the most basic demographic information that you need, since it makes the survey longer

4. Order your questions carefully (use logic!)

- Ask questions that will quickly weed people out in the beginning

- Prioritize the essential criteria you need the participant to align with before you ask specific questions

For example: Make sure you ask IF someone has thought about moving before asking them how often they have viewed apartments

- Ask about location first if you need in-person interviews

- Use a funnel approach

For example: Start with more broad questions, move into specifics, and then broaden out again with questions like demographic data

5. Avoid leading questions

- Leading questions will influence people to answer in particular ways, and skew your data

- Leading: How great was our coffee?

- Fixed: How would you describe our coffee?

6. Include a mix of open-ended and closed questions to avoid obvious answers

- Using a combination of open and closed questions helps to make sure you are getting the best participants. A 60/40 mix is safe, where 60% of questions are closed, and 40% are open-ended questions.

- Open-ended questions help you see how a participant would answer in their own words, without priming them to respond in a specific way

- Using closed questions in a non-obvious way can help you understand behavior patterns (ex: asking how many times someone viewed apartments in 3 months, and giving a range of answers)

- Adding an open-ended question to your screener survey can give you clues as to how much insight a participant will provide in your actual study

- One word responses, illogical rambling or cagey answers can all indicate that a participant may provide a low return on investment

7. Always include an open text field

- Always make sure you include an open-text area in each multiple-choice question, as it is impossible for you to know you include all options someone might need

- Ex: “other,” “not applicable,” “I don’t know,” or “none of the above”

Let’s go through an example:

We own a plant shop in Brooklyn, New York, where we sell groups of exotic plants. We have been posting our plants on social media, and people from around the United States are contacting us and asking if we have an online shop. We want to consider this as an option but aren’t sure what people would want or expect. We want to conduct user research to understand the following:

- How people would like to purchase plants online

- What do people expect of an online plant store

- What do they think of other online plant stores

- Get their opinion on a prototype of the online plant store

Our screener survey might include questions like:

- Have you purchased plants online? (Yes/No)

If yes:

- How often have you bought a plant online in the past six months? (Multiple choice)

- How many plants have you purchased online in the past six months? (Multiple choice)

- Where did you purchase from? (Short open text)

- How was your experience with buying plants online? (Long open text)

If no:

- Have you considered buying a plant online? (Yes/No)

- If yes, why have you not purchased one online yet? (Open text)

- If no, why have you never thought about it? (Open text)

Feel free to add more thoughts on how you would screen!

For more engaging discussion, please sign up for the User Research Academy slack group! And check out User Research Academy for free resources

If you liked this article, you might also be interested in:

Recommended resources for User Researchers

February 2021

I get asked quite often about any resources I can recommend for someone new to, or even seasoned, in the field of user research. Since I have found myself writing the same recommendations constantly, I decided to compile these into a list, which I will come back to and update!

Last updated, February 2021

Podcasts:

Since I have a dog, I spend a lot of time listening to podcasts while we go on long walks through Berlin. During this time, I love to listen to podcasts about user research. Not all of them allow me to come away with tangible action items, but they allow me to understand a different or new perspective. I love hearing about different ideas or challenges other researchers have faced. Here are my favorites:

- The Conversation Factory (my new favorite)

A fantastic podcast, hosted by Daniel Stillman, where he explores the edges of Conversation Design: the application of Human-Centered Design principles and Experience design to human discourse. - Dollars to Donuts

A wonderful podcast, hosted by Steve Portigal, where he talks with people who lead user research in their organization about all things user research. - Mixed Methods

A thought-provoking podcast, hosted by Aryel Cianflone, interested in the hows and whys of user experience research. Through interviews with industry experts and hands-on trial and error, they indulge and celebrate curiosity. - Awkward Silences

A podcast, by User Interviews, where they interview the people who interview people. Listen as they geek out on all things UX research, qualitative data, and the craft of understanding people to build better products and businesses. Hosted by Erin May and JH Forster, VPs of growth/marketing and product at User Interviews. - Aurelius

By Aurelius labs, and hosted by Zack Naylor, a podcast that talks to industry experts, discussing design and product strategy. Hear from leaders how they are solving the right problems and building products and features that matter most.

Slack channels:

There is nothing I love more than seeing a community of UX’ers helping each other. I truly believe a community is one of the best things for a field, and there are several amazing slack groups growing. I highly recommend joining these communities, as they are some of the best support out there.

- Mixed Methods

A great community for all things UX, both research and design. Join the growing community to post questions and help others in the field. - ResearchOps

A global community who’ve come together to discuss the operations and operationalization of user research and design research — also known as ResearchOps. ResearchOps includes the people, mechanisms, and strategies that set research in motion. - User Research Academy

A bit of a shameless plug here, since this is a slack channel I am growing. A community to be a support system, a go-to place for user researchers to find advice, and a community for an engaging discussion on important user research topics - Ethnography Hangout

A global community created for conversations about ethnographic methods. This is an interdisciplinary group wearing many hats from design to tech and research, so you don’t need to have any formal background in ethnography to participate.

Books:

There are some basic books I always recommend for people to read, which have a wealth of information about user research. Although these are more static than articles and podcasts, they serve as wonderful foundations and building blocks. When I get stuck on a problem, I still go over to my bookcase to pull out these books. These books include information on, both, qualitative and quantitative user research methodologies.

- Research Practice: Perspectives from UX Researchers in a Changing Field by Gregg Bernstein (I am a contributing author!)

- A Practical Guide to Measuring Usability by Jeff Sauro (one of my favorites)

- Just Enough Research by Erika Hall

- Think Like a UX Researcher: How to Observe Users, Influence Design, and Shape Business Strategy by David Travis

- Observing the User Experience (2nd Edition): A Practitioner’s Guide to User Research by Elizabeth Goodman, Mike Kuniavsky, and Andrea Moed

- Interviewing Users: How to Uncover Compelling Insights by Steve Portigal

- Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior by Indi Young

- UX Research: Practical Techniques for Designing Better Products by Brad Nunnally and David Farkas

- Measuring the User Experience (2nd Edition): Collecting, Analyzing and Presenting Usability Metrics by William Albert and Thomas Tullis

- Handbook of Usability Testing: How to Plan, Design and Conduct Effective Tests by Jeffrey Rubin

- Practical Empathy by Indi Young

- Quantifying the User Experience: Practical Statistics for User Research by Jeff Sauros

Blogs/Resources:

I am often scouring the internet for information on user research. After all, searching the internet is how we learn now. I love reading about different perspectives and thoughts on user research through people’s words. Instead of finding particular articles, I wanted to recommend the websites I reference the most.

- Neilsen Norman Group

One of the top websites for all things UX and a great place to find relevant information. One of the articles I send around the most from NN group is their article on only needing to usability test with five users - UX Collective

My go-to when searching for UX articles on Medium. They have a great selection of UX articles written by people in the field. What I love most about these pieces is that they are written by people who are experiencing the problems in real-time, and can give tangible advice/examples on how to handle them - dscout People Nerds

dscout is constantly putting out relevant information into the world of UX, and they touch upon many important topics, such as accessibility and repositories. They take real-world problems researchers are facing, at a global level, and provide content to help them overcome these hurdles. PS: I write for dscout, but find them extremely relevant regardless :) - Usability.gov

A bit old school, but a really comprehensive website all about usability and improving user experience. They have guides, templates, and documents to help you with better understanding, and testing, usability. - User Research Academy

Another shameless plug. I founded User Research Academy back in 2019 to help people get into the field of user research. I offer courses and mentorship in user research.

Facebook:

I only have one recommendation for Facebook, but it is such a wonderful community, so I wanted to make sure it got proper recognition.

I hope you find these helpful! As I mentioned, I will be coming back to add and update these!

If you liked this article, you might also be interested in:

5 Steps for Setting Up In-depth Interviews

In-depth interviews are gold. This user research method allows us to genuinely understand who our customers are and what they experience in their everyday lives. It’s a style of interviewing that goes beyond the customer’s interaction with our product. Of course, we still want to know how a product or service impacts them. However, understanding our customers as real people, with lives outside of our product, should affect the way we build our product or service.

How do you set up these research interviews?

Here are 5 steps to get started:

- Define your problem statement. This is the central statement the research seeks to understand. It is WHAT you will be studying.

Example: Choosing a software product is a very complex process; we seek to deeply understand how people make these decisions.

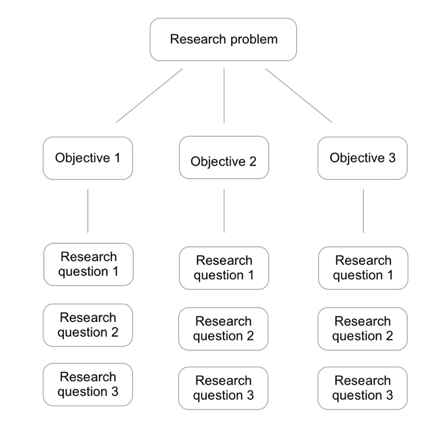

2. Define your research objectives. They should address HOW you are going to study the problem statement. Do this by breaking the research problem down into several objectives:

Ask yourself: “What am I trying to learn?” and “What must the research achieve?”

Example objectives:

- Understand the end-to-end process of how participants are currently making decisions on choosing a software product.

- Uncover the different tools participants use to make software product decisions.

- Identify any problems or barriers they encounter when trying to make decisions on software products.

- Learn about any improvements participants might make to their current decision-making process.

Identify what stage of the idea is being researched:

- A concept or idea: You need to understand the process people are currently going through (generative research)

- A prototype: You need to uncover what people think about the prototype and how they expect to use it (generative + usability testing)

- Live code: You need to evaluate the performance of the product and what people think about it (usability testing)

3. Target the correct participants for the study. Before you start recruiting, you have to understand who your users are so you can optimize recruiting efforts. Talking to the right people is a fundamental part of effective research. What are some ways to do this?

- If you haven’t already established personas or a target audience, take a day to define your target user. Do they work in marketing, sales, customer support? Probe internal stakeholders for key insights and come up with proto-personas.

- Scope your competitors, and recruit based on their audiences. Bonus: You can even recruit people who use the competitor’s product, and during the interview, ask them how they would make it better.

4. Write a research plan. Research plans contain all of the necessary information about the research project. Use it as a kick-off document to distill core goals and align the whole team.

5. Align the team. Once you have finished the research plan — or even before — sit down with the team to discuss the research problem and objectives. By doing this, the whole team can brainstorm questions they would like answered or concepts they would like to understand better through the research.

With these five steps, you should be able to start generating critical insights from discovery research!

Why you should always aim for open-ended conversations

It isn’t all about asking questions.

The always in the title might be a little bit of a lie and slightly misleading. I must admit, not every conversation I have is open-ended. There are times when I am human (other times, I am a robot) and ask a yes or no question, or even a leading question. However, I do my best to have the most open-ended conversations as often as my brain can keep up with my mouth.

Open-ended conversations are the magic of user research interviews. They allow you to understand users’ mental models and dig into the lives of your customers.

Discovering how and why users think a particular way is key to delivering great insights to your teams. With just a list of basic interview questions, it is nearly impossible to uncover the mind of the person sitting next to you.

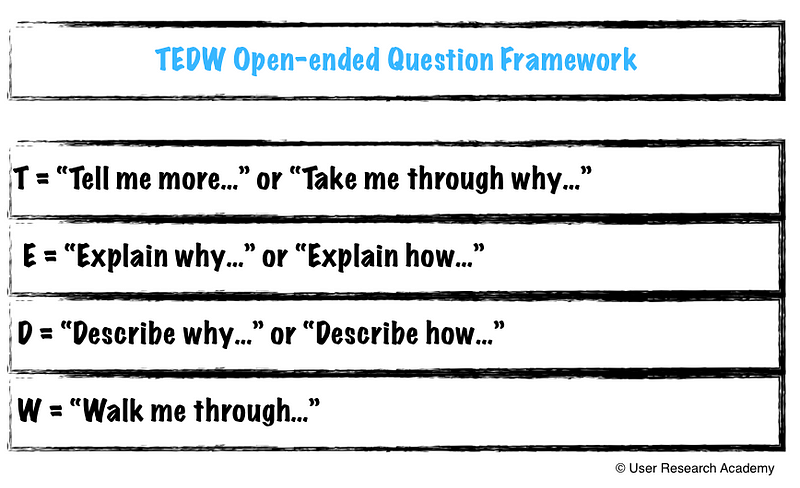

There is one particular framework I use to ensure I do this as much as possible. Unfortunately, I can’t remember exactly where I learned this from (it was years ago), but if anyone recognizes it, please tell me.

The TEDW Framework

I have used this framework since I can remember, and it has helped me become a better researcher. With this, I spend less time thinking about what to say next. Additionally, the TEDW framework means I am not always asking, “why, why, why” repeatedly, but I am still able to dig deeper into what the user is saying.

Another reason I love this framework is that it turns interviews into conversations and storytelling. What you want and need from users is to have them recall specific memories and tell you stories about those previous experiences. The TEDW framework enables you to get into this mindset. It takes the pressure off of the researcher and the interviewee.

Another cool thing is that the TEDW framework is not about asking questions, but about having open-ended conversations. Instead of asking people direct questions, you are using active listening and open-ended statements to extract the stories from them. Using this technique makes it a lot easier for participants to give you reliable past data, as it reduces biases that come through in research.

Some examples

To demonstrate this further, here are some ways I would reframe questions into the TEDW format. Since Netflix is such a famous app/service people use, I will use this as an example:

- Original question: “When was a time you Netflix?”

- TEDW question: “Tell me about the last time you watched Netflix.”

- Why I rewrote this: If you start with a question like “when was the last time…” you are not prompting the user to tell us any stories. You are asking a specific question. Let’s start broad, and then you can use the “what, when, where, how, why” to dig deeper into setting the scene.

- Original question: “Were you doing other things while watching Netflix?” -> follow-up: “Why were you shopping online while you were watching Netflix?”

- TEDW question: “Describe what else you were doing while watching Netflix.”

- Why I rewrote this: The original question is direct and a technique I will sometimes fall into. The person might not know why they were shopping online while watching Netflix, but it is more important to know first what they were doing and to have the participant set the scene. Then, if you are a team that is trying to understand the way people go in and out of a show, you can dig deeper into that area. You might not get as reliable of data if you are asking these direct questions.

- Original question: “Why were you feeling frustrated with Netflix when you couldn’t log in?”

- TEDW question: “Explain what you mean by frustrated.”

- Why I rewrote this: There are two reasons to rewrite this question:

- You have to understand what that person means by frustrated. People often have different perceptions of what emotions mean, and it is essential to understand that from a user’s perspective, not from your assumed mental model of the feeling. My frustration might be your anger or sadness.

- Again, this is a direct question. The participant might not know why she was frustrated. If you leave it more open-ended, she will end up recalling the scene, which gives you ample opportunities to dig deeper into what is most important to the participant. And, you should care about what the participant cares about.

- Original question: “What made you turn on Netflix last time?”

- TEDW question: “Walk me through the last time you started watching Netflix.”