Why you should always aim for open-ended conversations

It isn’t all about asking questions.

The always in the title might be a little bit of a lie and slightly misleading. I must admit, not every conversation I have is open-ended. There are times when I am human (other times, I am a robot) and ask a yes or no question, or even a leading question. However, I do my best to have the most open-ended conversations as often as my brain can keep up with my mouth.

Open-ended conversations are the magic of user research interviews. They allow you to understand users’ mental models and dig into the lives of your customers.

Discovering how and why users think a particular way is key to delivering great insights to your teams. With just a list of basic interview questions, it is nearly impossible to uncover the mind of the person sitting next to you.

There is one particular framework I use to ensure I do this as much as possible. Unfortunately, I can’t remember exactly where I learned this from (it was years ago), but if anyone recognizes it, please tell me.

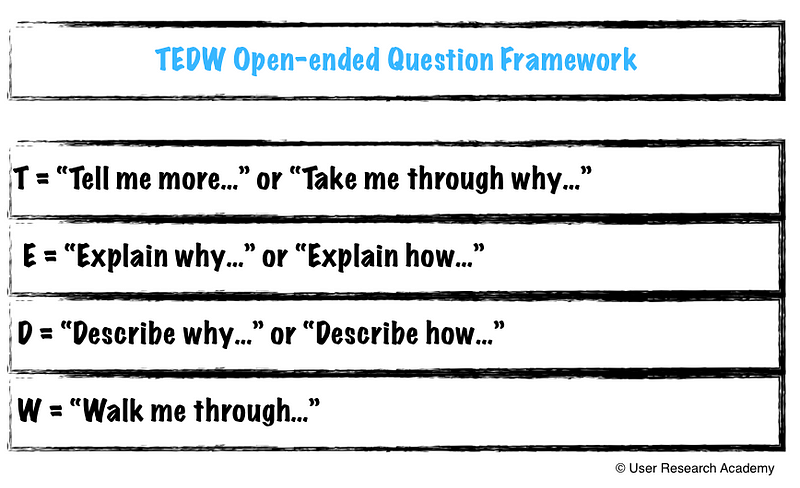

The TEDW Framework

I have used this framework since I can remember, and it has helped me become a better researcher. With this, I spend less time thinking about what to say next. Additionally, the TEDW framework means I am not always asking, “why, why, why” repeatedly, but I am still able to dig deeper into what the user is saying.

Another reason I love this framework is that it turns interviews into conversations and storytelling. What you want and need from users is to have them recall specific memories and tell you stories about those previous experiences. The TEDW framework enables you to get into this mindset. It takes the pressure off of the researcher and the interviewee.

Another cool thing is that the TEDW framework is not about asking questions, but about having open-ended conversations. Instead of asking people direct questions, you are using active listening and open-ended statements to extract the stories from them. Using this technique makes it a lot easier for participants to give you reliable past data, as it reduces biases that come through in research.

Some examples

To demonstrate this further, here are some ways I would reframe questions into the TEDW format. Since Netflix is such a famous app/service people use, I will use this as an example:

- Original question: “When was a time you Netflix?”

- TEDW question: “Tell me about the last time you watched Netflix.”

- Why I rewrote this: If you start with a question like “when was the last time…” you are not prompting the user to tell us any stories. You are asking a specific question. Let’s start broad, and then you can use the “what, when, where, how, why” to dig deeper into setting the scene.

- Original question: “Were you doing other things while watching Netflix?” -> follow-up: “Why were you shopping online while you were watching Netflix?”

- TEDW question: “Describe what else you were doing while watching Netflix.”

- Why I rewrote this: The original question is direct and a technique I will sometimes fall into. The person might not know why they were shopping online while watching Netflix, but it is more important to know first what they were doing and to have the participant set the scene. Then, if you are a team that is trying to understand the way people go in and out of a show, you can dig deeper into that area. You might not get as reliable of data if you are asking these direct questions.

- Original question: “Why were you feeling frustrated with Netflix when you couldn’t log in?”

- TEDW question: “Explain what you mean by frustrated.”

- Why I rewrote this: There are two reasons to rewrite this question:

- You have to understand what that person means by frustrated. People often have different perceptions of what emotions mean, and it is essential to understand that from a user’s perspective, not from your assumed mental model of the feeling. My frustration might be your anger or sadness.

- Again, this is a direct question. The participant might not know why she was frustrated. If you leave it more open-ended, she will end up recalling the scene, which gives you ample opportunities to dig deeper into what is most important to the participant. And, you should care about what the participant cares about.

- Original question: “What made you turn on Netflix last time?”

- TEDW question: “Walk me through the last time you started watching Netflix.”

- Why I rewrote it: Again, you are getting at a story with the TEDW format. You are asking them to recall a memory of what was happening, instead of asking them to answer a specific question on what made them turn it on. With the context of the story, then you can drill down into subjects such as, “what were you feeling?” “When was this?” “Describe the scene for me.” You want to focus on the story the participant is telling you, not the answer to a question.

Using this framework doesn’t mean that you never drill down and use questions like, “why did this happen,” or “when were you doing this?” Instead, TEDW is a way to start conversations, and a way to begin the storytelling process. Once the participant starts giving you nuggets of the story, you can dig deeper into the critical parts based on our research goals.

Give it a try and tell me how it goes!

Want to share with others? Feel free to use this condensed slide deck.

Interested in more user research? I teach an Introduction to User Research Course and am available for one-on-one mentoring. Check out the User Research Academy. Please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions.