An example of a generative research interview

I always get asked about how I conduct research interviews, and each time I do my best to explain my techniques. I mention research plans, TEDW techniques, not asking about the future, and being careful not to ask leading questions.

However, I constantly struggle with how to describe my research interviews. Since I rarely follow a script for generative research interviews, it is hard for me to write down a list of questions because I generally base what I say on the participant’s response. I also tend to go slightly off-script during usability testing if I find an interesting thread to follow that might bring some solid insights.

After years of practicing, I feel most at home during research interviews. Yes, I definitely can still get nervous before a research interview, but generally, they are the highlight of my week. I think of research interviews as a window into someone’s life, and I am lucky enough to get a peek. For me, interviews are the coolest part of being a user researcher, which is why I get so frustrated not being able to answer one of my most received questions.

So, I decided to try something new that might help. Instead of writing out the basic structure of my user research sessions, I thought it might be more helpful to conduct an example research session and write out the exact script.

The idea

My fiance, a product manager, was kind enough to volunteer to be my research subject. We talk in-depth about quite a few topics, but we decided to talk about one of his passions: boardgames. In this example, I sit down with him to better understand how he decides to purchase a particular board game.

The interview

I only transcribed the first thirty minutes (out of about an hour), but it should still give a good idea. Want to listen as you read? Check out the sample interview here.

Introduction

N: My name is Nikki. I am working on a project right now to better understand how people think about purchasing board games and how they actually go about purchasing them. So I mean, user experience researcher at this company, and I wanted to understand your thoughts and your thought process on how you go about purchasing board games. So this session will only be about 30 minutes. And there are no right or wrong answers. So I want you to answer honestly. You’re not going to hurt anybody’s feelings with your feedback. Since we’re going to use this, your feedback and opinions improve our product and purpose. Do you have any questions before we begin, though?

C: That will make sense?

N: Okay, cool. Do you mind if I record this session before we start this?

C: Absolutely fine.

Diving in

N: Okay, cool. Awesome. So as I mentioned, I want to understand a little bit better how you think about purchasing board games. Um, so just to kick it off, could us think back to the last time you purchased a board game on your own, not a gift or anything, and kind of walk me through from when you first realized that you wanted or needed the board game all the way through actually purchasing it?

C: Yeah, sure. Um, so I really like board games. I’m not trying to say need as many as I have. But for me, it’s been like a hobbit in German. And I like to have kind of a diverse board game. Depending on who we play with, there are a few things that so I think maybe contextualize it a little bit. The last board game was called charter stone. I saw actually I was in a board game store said we had brunch with a friend, and we were walking past a board game store on the way back. And I dropped in. It was actually the box that first attracted me to it. I thought it was a really well-designed box. And aside to read it, and it was a legacy type board game. To me, it’s one of those that changes every time you play it. So what you do in one game will affect the next day. So normally, for I buy a board game, I actually also put alliances quite a popular website for games called BoardGameGeek, which is like the online home of board games. So on there, you’ll have forums discussing them, reviews for each game. And reviews will take things like complexity into account, learn the number of players, and the mechanics because there are many different mechanics in board games. So if you think of it a bit like a video game, you can, you know, you can build a base, or you can do a first-person shooter or car racing game. Like board games, you have different mechanics, and people prefer different mechanics on what they’re doing. So while I was in the store, I quickly looked it up. I saw it had a really good rating there. This one was made a little bit more of an impulse buy. And so I bought that one on the spot because there were the mechanics are involved. And it was a theme that I liked. The artwork was beautiful. And then at least initial reviews that I read on Board Game Geek really positive, so I bought it.

N: Wonderful. Awesome. So that was a lot of information. And so what I might do is I might actually go back and talk to you a little bit about what you what you just talked about. But when you say that you bought it, can you just describe that portion a little more. You were in a store?

C: I’d looked at a couple of ones. I picked it up and did the kind of browsing things on my phone. And just to see what Board Game Geek was saying what some of the big reviewers were saying about it. And it was generally positive. And so I picked up I wandered around the store for a little bit longer. It was more a case of what else might I buy? I said, there’s a board game store. There was nothing else typical that I really wanted that day or caught my eye. So I went and bought it was pretty straightforward.

N: Well, awesome. Going back way to the beginning of when you mentioned that you dropped into the board game store and saw it was there anything that kind of triggered you dropping into that board game store in particular.

C: It’s my local board game store. So so it’s the one that’s nearest to where I live. I bought a few games there before they’ve always really friendly, really nice, and there’s a huge selection, which is good. And we finished brunch, and it was literally two streets away from where we were eating, so it’s close by that as I might as well. And Saturday tends to be the day that I indulge in my hobbies. I have a couple of hobbies, so if I’m near the local store for that hobby, I maybe go in and just kind of browse and see what’s available. So that was it.

N: Okay, so it was location-based like you were close to it. So it was easy to stop by. And so you mentioned that the board game like the actual box caught your eye. And you said that it was like well designed, can you talk a little bit more about what you mean by well designed.

C: So this one’s actually quite a fun example. Because there’s almost nothing on the box, if you think about a box, you’d get with Apple, where you have an iPhone on the front, and then no information. It was kind of like that. The box is very clean, very white and actually stood out against a lot of the board games in the store, which is why I noticed it the first time. I then went to the back. There’s a brief summary of the mechanics, which I said were the kind of mechanics I liked. So kind of building strategy and building games, a nice preference of style, there are the little artworks, but there wasn’t that one was very clean and very crisp, and that I was pretty impressed by that. So I like legacy games. I like village building games. And obviously, at that point, it wasn’t enough for me to purchase it. I was really interested. And that’s when I went to Board Game Geek. And I got some information.

N: That’s really interesting. And so you said that that box was different because of maybe the clean and the lack of information on the box? Could you give an example maybe of what the board games normally have on the box?

C: Yeah, it depends on the box. You’d normally get a lot of information on the side of them. So you’ll normally have, it kind of depends. So on the front, you normally have obviously the title and some illustrations on the back or the side, you will tend to get kind of function information to how many players rough time how long it takes to play. And some of the mechanics that are involved with the dice base game is a card game is it, those kinds of things. So the mechanics I mentioned before. And then on the back, normally, you get a picture or an overlay of what’s included in the box, if I think about my favorite game, The Game of Thrones board game, or Imperial settlers. If you look on the back of that box, it gives you an overview of what it might look like when you’ve set. This box doesn’t do that because it’s more of a story mode. Because I said it’s a legacy game. You don’t know what cards are there. That’s actually one of the things when you open the box is a big thing says do not read the cards because you’re meant to play through the story mode. So your game evolves, depending on your decision. So you’re not allowed to say no, and it looks like and also by printing on the back of the box. It’s not representative because it’s going to look different for every player based on their decisions. So that one, I think, is very different from most of the games that I play. And I think after the election did a good way of giving a hint of mystery about what’s involved.

N: That’s super interesting. So you mentioned that, since there wasn’t a lot of information, you went on to Board Game Geek to go and kind of look up the reviews and the different mechanics and more information. But before we get into that, and how you went through that process with charter stone, do you also go on to Board Game Geek when you get all that information on the box?

C: Yes. Oh, Board Game Geek is a pretty good community. It’s quite a diverse community. It’s like the authoritative source of like board games online. Like that’s the place you go to check it. For example, if you’re playing a game and you’re not sure about a rule, or you feel that it’s two rules that are conflicting, almost everyone I know will go to the board game geek website before they go to the official, the official website because normally it’s easy to find other people obviously because they the official companies can test the game like 100,000 times. So people do it. And also, if someone’s got an official answer from a company, they will consolidate there. So Board Game Geek is pretty authoritative. It’s also very detailed in what you’re looking for. And the website’s not the prettiest, I’ll be honest, but it’s very functional. You find what you need to find, which is great. To go back to your question, yeah, I will use Board Game Geek pretty much every time. I will also use it sometimes if I’m at home and browsing online for a board game. I will use maybe five or six big reviewers that I will also see what they’ve said about again.

N: Cool. Awesome. Thank you. That’s really helpful. Could you talk about a time when you have seen a game online or in a store and purchased it without going to board game geek?

C: Yes, but only when I’ve played the game before. For example, if I played with a friend so Game of Thrones, the board game is actually my current favorite board game and has been for several years that I bought off Amazon. Immediately I finished I went to I got introduced to it by one of my other friends who went down we spent the day playing. I laughed. I was like, I’m buying this game because I played it. And I had the experience. And I use I guess I use this on Board Game Geek as a proxy, I proxy other people’s experiences to be like, would this apply to me? And if I played it with them, and I like it, I will buy it without checking Board Game Geek.

N: Okay. Interesting. So it seems that if you’ve had the experience of playing the game, you feel more comfortable purchasing it without visiting board game geek.

C: Yeah, because at that point in my experience, I know I like it. As I said, I think with Board Game Geek, I use it when it’s new for me. You can read the packaging, maybe less overcharged soon, because the packaging, but generally, you can get an overview of how the game works, doesn’t say how the game plays, which is very, which is a very different thing. And there’s a lot of board games out there. They’re not all fantastic. And there are multiple reasons that that will be the case. So I tend to trust the community of gamers about what they like what they do, like, there may be a chance I’m missing out on an awesome game that I would think was fantastic because the community doesn’t like it. But generally, I found that the games that I buy, the process of buying games generally seems to work for me.

N: Okay. And that’s the process of looking and looking it up on Board Game Geek.

C: Yeah, it’s about more validating. So I’ll come across it in bed. So a friend will mention a game, or I’ll see online I see in a bookstore for game geeks, which is my way of getting more information. What is the experience of playing this? Occasionally, I get games recommended to friends. And if a friend has recommended the game to me, I’ll check it out. But I probably still will check Board Game Geek if I haven’t played it myself. Okay. Okay. Even if it is a recommendation from a friend, you are more likely to. Yeah, I think it depends. I’ve got many friends who play board games, and they’ve all got different preferences. I mean, there’s a couple of friends who like or enjoy almost the same games. So if they recommended them, I probably would take it off the bat as a smart purchase.

N: So looking at board game geek since it’s interesting to see what other people say. Cool. Yeah. And you’ve mentioned a few times that you’re looking for, like the experience. Either like the experience that you had yourself personally or on board game geek, you’re kind of looking for what the experience might be. Can you talk a little more about how you figure out what that experience is, especially on board game geek?

C: Yeah, so Board Game Geek actually has a good way of quantifying this. So they have two main numbers. One is complexity. And one is geek rating. Complexity is given a rating between zero and five by how complex the game is. And then geek rating, which is how good it is how high it sits in the ranking. For example, I know my two of my favorite games, Game of Thrones and imperial settlers, I know where they sit on that rank. So I benchmark all the games against those. Of course, it depends on what I’m buying them for. If it’s like a party game, so the kind of game you played with people, then that’s different. So there’s a common one that people would know on things like Cards Against Humanity would be considered a party game, or resistance, which is ones where you have to pretend to be a secret agent, those kinds of things. For those of us who want an easier and a lower complex rating, because you the idea is that you find a group of people probably haven’t played this before, and you sit down and get started playing. But something like the Game of Thrones has a much higher complexity rating. And that’s a bit more for kind of people who like hardcore games. You will sit for five or six hours, probably more. As long as the corresponding geek rating score is high on it as well. You also get an overview of the mechanics. I don’t really like dice-based games. I don’t like the chance. I prefer strategy games where I can plan. Yeah, roll the dice. That’s when I’m not really into that. For example, those put me off because I’m not in control. I wouldn’t think I played a really good game instead of I got really lucky, which seems which is not as much my interest.

N: I don’t know if you have the answer to this question, but those dice games, do they vary in complexity as well, or could they potentially vary in complexity as well?

C: Good question. I don’t play as many dice games. So I don’t think it was well informed. It depends on the game. If the dice mechanic is one part of the mechanic in your game, you can still have a very high complexity rating. It’s a game where you just roll the dice, and then yet your outcome is probably lower. Monopoly is considered a reasonably straightforward game; everyone’s played Monopoly. But it’s pretty straightforward, right? You roll the dice; you move that far around. That’s a sensitive premise. And there’s a lot of luck involved in that, where you land. I don’t enjoy that as much. There’s a Battlestar Galactica board game made by the same company that makes Game of Thrones board game that has a dice mechanic in it. But many other things are going on at the same time. It just introduces the random element of space battle actually, or events happening. It’s a reasonably small mechanic, but it can be a bit annoying when it goes the wrong way. But it exists. And it’s a really good game. The dice mechanic is one that I’m not a huge fan of in it. But I understand in that situation, you have to have a degree of randomness. Otherwise the game, the game wouldn’t work. You don’t have that degree of randomness, for example, in the Game of Thrones board game. Right? You can be strategic and play it through and control as much as you can always control the other players around you.

N: Cool. All right. Awesome. Thank you. So kind of, kind of going back to, to that to the, to the two ratings, that they use the complexity and the geek rating. Yeah, the Geek score. Does that kind of roll up into like an overall rating? For the board game? Like, Is there like a zero to five stars? Zero to 10? stars?

C: Yeah, so the geek rating goes from zero to ten. I can’t remember where the ranking score comes from. It doesn’t come from a combination of complexity because you can have a game that is like 10, out of 10, and very complex, but people still love it. And it’s worth the complexity. So the complexity core doesn’t, as far as I know, factor into it. I think the geek score is the main driver where it sits in the ranking. For example, I know that Game of Thrones sits at like 7.6 on the geek score, and 3.65 and the complexity score. So I said that’s my benchmark. But for example, I know some games appear higher than Game of Thrones in the geek score, I just don’t enjoy playing. It’s a bit like there are games that rank high, but they just, they’re just not my style. Arkham Horror, for example, is one of them. It should be a similar game, but I don’t like it.

N: Okay, interesting. So that brings me actually into the next question that I have. Do you weigh both the complexity rating and the geek score? Pretty equally when you’re deciding? Or when you’re looking at something?

C: No, no the geek score for me is normally more important. The complexity rating is a lot of great material online, like, you know, how to play and guides for playing. So the complexity doesn’t really bother me. And the places only concerned for example, if you if I found a party game that was highly complex, I probably wouldn’t buy that because I don’t want to teach everyone. I would want to sit down and play and have fun. I don’t spend an hour explaining the rules to ten people. That’s not fun for anybody involved. It’s one of the reasons that Game of Thrones, for example, has such a large onboarding time. If you can spend maybe half an hour explaining the rules after they’ve watched a 20-minute tutorial video. And then after the first game, they’ll probably have how to play and the second game is gonna be loads of fun for them. Like Game of Thrones has a long onboarding time, but for me, it is well worth it. It’s a really great game. If you’re into the theme of hard to game like resistance or Exploding Kittens, you want to be able to explain it in 10 minutes, and the complexity rating is way lower than the complex games like Game of Thrones, Imperial settlers. Their complexity score is higher. There are lots of things going on with it. But it’s a great game for more hardcore gamers. I wouldn’t play that with my dad because my dad’s not as much into it. My friends who were in my board game group, they’re super into that kind of level. And then you’ve got some people that may be a bit high for, but there are other games that will sit in the middle.

N: Awesome. Cool. That’s, that’s perfect. If I’m understanding correctly, the Geek score is a little bit more important than the complexity rating.

C: Correct. And it depends on the situation.

N: Yeah. Okay. Cool. And so you mentioned that you benchmark generally against Imperial settlers and Game of Thrones. Can you talk about what you mean by like, benchmarking?

C: Yeah, it’s more just to anchor myself, so I know, hey, these are two games I really love. This is roughly what the community thinks of them in terms of complexity and in terms of rating. When I go and look at another game, either community saying these are better or worse. It’s just an anchor point really. I just take the games I know and try to compare them but it’s not always right. I said, there are games that rate higher, that I don’t enjoy as much. And some games really lower. So it’s more just a starting point.

N: Okay. Can you give me an example of a time where you’ve seen like a lower rating and have actually enjoyed or bought the game? Hmm, good question. It doesn’t have to be like an exact name.

C: Either way, I can tell you about a time that there was a game that I was ready to buy, but I didn’t enjoy it as much. Let’s see. Yeah, there’s one called Seven Wonders. That did not addict me or hook me as much as Game of Thrones or Imperial settlers. It’s a great game. I enjoy playing it, but never got into the rhythm as much as the other two. And I’m not totally sure why. Maybe I don’t know. Maybe I like the themes of Imperial settlers and Game of Thrones slightly more. But yeah, so that was a game that was rated higher by the board game community. But I know that I enjoy it less. It doesn’t entice me to play as much. I’m thinking hey, why don’t I play today? It’s never the game that jumps to mind like Imperial settlers or Game of Thrones. There is my default like, yeah, I really love these games.

N: Hmm. That’s really interesting that you say that. Because you’re saying it’s not that you necessarily enjoyed it less, but it doesn’t jump to your mind. And it doesn’t like entice you. And I know you said you just said like, I’m not exactly sure why. But I’m wondering like, is it because you’ve cited like mechanics and themes before as ways that you choose board games? And is it would it be something like that?

C: You get really bought into what you’re doing. So Game of Thrones is the one you play for five or six hours. You play a particular house, and I’ve read the books and TV shows. So if I’m and I lose a footman, I’m like, I know, I’ve lost the footman. Yeah. Similarly, with Imperial settlers, it’s a much shorter game than Game of Thrones. But you pay for your faction and you grow your empire. With Seven Wonders, great game really strategic, different ways of playing it. But the games are much shorter, I think like an hour tops, and there are the different factions and you get less bought into them? I think at least from last time I played, it’s not, you know, you don’t get as invested. Perhaps that’s what it is.

N: So when you say that you’re not as invested or as bought in? Can you explain a little bit more what you mean about being like invested in that game? Yeah, invest in the success of that faction that you’re playing, or that team that you’re playing? Or that civilization that you’re playing?

C: I guess there’s more. There’s more persistence on the End Game of Thrones in Imperial settlers, like your decisions feel like they take longer. I think when I think back, like, I deserve almost a story that goes with Imperial cycles in Game of Thrones, like you play through. And you can remember that time that someone did an amazing move. And like backstabbed in Game of Thrones, or Imperial status uses or there’s always certain like combinations of cards that your opponent played and the damage was really good. Like you learned a lot from it. Where Seven Wonders is very replayable it’s always a different game. But I very, I really remember any time I was like, Damn, that was awesome. Or I was like, Oh, right, that we were trying to get those from the other games. So maybe it’s that kind of book that I was thinking about.

N: Okay. Um, I don’t know if you can answer this. But if you could change something about seven wonders to make it more like the Game of Thrones games with the Imperial settlers games that you’re talking about? Like, what would you change?

C: I have not played in about a year. So it’s hard to remember. And sometimes I don’t want every game that I play to be as intense, for example. Seven Wonders, I think is, is a very strategic game. It removes a lot of the emotional elements that you may get in Game of Thrones. It’s so nice, I’m not sure I’ll change it. I do enjoy it. When I said I do enjoy it when I play it. It’s just a different type of enjoyment.

N: That’s interesting. Okay, so going back to the actual like decision that you made to buy it. So that seven wonders were rated higher?

C: Higher, yes.

N: And Game of Thrones?

C: Okay, I think complexity is definitely lower. Definitely low.

N: Um, okay, so it was higher on the geek rating. So that that kind of pushed, did that push you towards that?

C: Yeah. We bought this game because I was back in London with a few of my friends where we played a Game of Thrones in Paris, it was a lot together. And we considered buying another game. There was no point buying Imperial Settlers since we already had a copy of it. We went to the board game cafe that we used to go to in London, and we spoke to the guy there. And he actually said Seven Wonders is very popular. Consider it. We checked out on Board Game Geek and it is rated highly. So we took it home. And we spent most of the weekend playing. So I think it was a combination of things like we wanted something different than what we had before. Like I didn’t want to buy another copy of the game I already had. We wanted to do something different. And situationally, that’s when I had the opportunity to buy it. And I’ve seen someone mention it loads of times on Board Game Geek. So it’s a game that I was aware the board gaming community enjoyed. So it seemed like a good opportunity to buy it.

N: Okay, and so you bought that one. Yeah, took it home, and then you guys played it?

C: Yeah.

N: Okay, cool. Um, so do you think that there was anything that you could have found on Board Game Geek? Or like any sort of information that would have like helped you maybe not buy this game? Or you know, reconsider the purchase because it sounds like that geek rating weighed pretty heavily as well as like that recommendation.

C: It’s like it’s a very good game and I see why it’s rated highly in the community, but it’s not something I like. The whole idea of board games is that you find something that you like or enjoy anything that I would have made me change my mind not to buy that or buy something else. That’s a great question. i guess both

N: Let’s tackle not to buy that first. Or if it since it seems like this game doesn’t seem like a bad game to you if you want to think about something that was like more highly rated that actually, you didn’t end up liking, if you have an example of that maybe that would be easier to come up with.

C: Yeah, I honestly like all the games I have. I just like them for different reasons and in different situations. I can’t think of one honestly.

N: How about something similar to Seven Wonders had a higher rating, but you regret purchasing it if you have one of those.

C: There isn’t any game that I necessarily regret purchasing. I don’t play a number of games as often as I shouldn’t have maybe not got the full euro value out of the game that I’ve purchased. So Game of Thrones it’s not a cheap game to buy and with all the expansions probably over 100 euros, but I played over 100 games of it now. There are other games that I’ve played like five or six times that would have cost 50 euros. But the times I played them, I’ve enjoyed them. They’ve been, they’ve been a bit more situational.

N: Okay. So it doesn’t seem like there’s any sort of regret or like, I wish that I could return this.

C: No, there’s no.

N: How about Have you ever felt like you wish you could exchange it for a different game?

C: No, so I quite like having a collection. I liked having the diversity collection. I’m the same with books. Like I’ve got a large book collection.

Tear it apart!

I am no stranger to making mistakes, and I am sure I made plenty during this particular interview. I encourage you to use this example to highlight what you might do better and things you would like to avoid in your interviews!

Since I interviewed my fiance, I was a little more informal, but this is my general tone and flow. Here are a few things I missed and would change:

- Getting written NDA and consent from the participant

- Including warm-up questions. My favorites are: “what are your favorite hobbies?” “what do you do in your free time?” “have you tried anything new recently?”

- Saying “awesome” and “cool” quite a lot (internal facepalm)

- Avoiding the future-based questions

Basics on how to conduct card sorting

And why it is one of my favorite methods.

There are a few reasons I love card sorting so much. The method is simple, effective, and fun to participate in (for both the moderator and the participant). I was surprised when I realized I hadn’t written an article solely on card sorting. It deserves it’s time to shine.

There are a few reasons I love card sorting so much. The method is simple, effective, and fun to participate in (for both the moderator and the participant). I was surprised when I realized I hadn’t written an article solely on card sorting. It deserves it’s time to shine.

I first learned about card sorting about six years ago. I was talking to a colleague, and we wanted to redesign our platform for a different set of users. We were currently supporting hotels and hotel staff, but we wanted to see if we would also help staff working in residential buildings (think high-rise apartment buildings in New York City).

Now, of course, there was a lot more that goes into a conversation like that then merely bringing up card sorting. We had done qualitative research with the residential building staff already. We were trying to think of how to pivot the platform. How might we use the existing skeleton to support the differences in workflow?

I was still relatively new to the field of user research, and it was back when I believed there were only two methodologies: discovery research and usability testing. I hadn’t done too much experimenting with other methods for a few reasons. I hadn’t learned about theses methodologies, I didn’t feel confident with them, and I had no real guidance on how to implement this.

We set up our goals for the research session. We wanted to accomplish a few things:

- Understand what current features made sense to these users, and which were missing

- How the users categorized the different features and information on the platform

- How users would imagine the platform to look in terms of navigation and nesting

- The flow users went through in their day-to-day

Many great goals. After a week, we started usability testing. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work. I tried to ask them how they would navigate the current platform and stumbled around with future-based questions that were most likely leading. At one interview, I remember getting out a piece of paper and just having the person write down a list of what they wanted.

Major fail.

We wanted a mix of understanding users’ mental models and information architecture. That is where card sorting shines. After that last interview, I went back to the drawing board, Google.

At the time, I didn’t know what information architecture was, but I eventually put together enough of the right search terms to find card sorting. After reading a few articles, we went to work.

What is card sorting?

Card sorting is an activity in which you give cards to a participant and have them order the information in a way that makes sense to them. These cards can have information written on them, can be blank or a combination of the two.

These three scenarios line up with the three different card sorting techniques there are. Each of them has a time and place. My favorite is mixed card sorting.

Closed card sorting

Closed card sorting is when each participant gets a set of cards with information already written on them. They are limited to using these cards. This approach is very evaluative and is best when the terminology or concepts are well-defined and established. It can give you apparent patterns on the cards. The significant cons for this, however, is that you might not fully understand the user’s mental model, as they have to conform to what you wrote on the cards.

Open card sorting

Open card sorting is pretty much the opposite of closed card sorting. Participants create categories and concepts of their own and then order them. Open card sort is great for exploratory work, and understanding how users relate to, organize, and define different concepts. It can lead to a better understanding of terms and definitions. However, the con for this approach is that the patterns are usually not as clear as with closed sorting.

Mixed card sorting

Mixed card sorting includes cards with predetermined information, but allows the participant to create new categories or concepts that may be missing. When I do mixed card sorting, participants can “edit” the pre-written information. Mixed card sorting is my favorite because it allows for both evaluative and generative work, although you may still run into the same cons of fewer distinct patterns.

How do you choose?

First off, determine if you are in a generative or evaluative phase of the project.

Would you feel comfortable/confident in defining terms, concepts, and categories for your users? Have you conducted previous research that would help you correctly identify them? If yes, you can then use closed card sorting to evaluate the patterns better.

If you are starting from scratch, or don’t feel confident in creating cards, I would recommend going with either open or mixed card sorting. This way, you can better understand how users are defining these areas, and then go ahead with a closed card sorting after that.

To decide between open and mixed is up to you. If you know that some concepts have been validated, but others not, then go for the mixed, if you want to go all out discovery, open will suit you best.

Regardless, make sure you always capture the running commentary as the participants are placing, writing, or organizing cards.

How to run a card sorting test

Many different components go into a card sort, so I split them up into three main steps. I also referenced articles that go more into detail when it makes sense, such as with defining the content of the cards.

Before the card sort

Now that we’ve talked about this magical methodology. Let’s run one.

Define your research goals. As wonderful as card sorting is, it has its time and place (as does every other methodology). To be effective, you need to make sure your research goals match up to your methods.

The common goals that align with card sorting are:

- Evaluating a users’ mental model on the information architecture of a product/service

- Understanding how concepts relate to each other in the mind of the user and the hierarchy of them

- Uncovering definitions, terms, or ideas that might be missing or misunderstood

Decide what card sorting method you will be using. Depending on the phase of your project, choose between open, closed, and mixed. If you aren’t sure, I always recommend mixed. If you are super tight on time, you can do a closed card sort and then, in the end, ask users what they would change.

Writing the cards. If you are doing a closed or mixed card sort, you have to write the cards. Knowing what to include in a card sort is the tricky part. What you write on the card depends on the project. The most important part is not to include more than 40 cards in your card sort. Since deciding what to write for a card sort is an extensive process, I wrote another article on that here. That article is all about how to write cards for card sorting.

Setting up the card sort

- Usually, card sorts last 60 minutes, so plan for that amount of time

- Recruit 15–20 participants for this kind of research

- Get the cards ready

- Make sure there is enough space to spread out all of the cards on a table or ensure there is enough wall space if they are hanging them

- If you are conducting your card sort online, make sure you have sent the link to the participants and tell them they will need internet access

- Get someone to help you during the session to take notes and observe what you might miss. They can also help with recording the meeting

- Go through the session to practice before with a colleague to make sure everything makes sense before inviting the participants

Moderating the card sort

- Give the participant the set of cards (or have them out on a remote tool). Walk them through what the session will be like and explain what you are looking for them to do. In each scenario, mention that any cards that are confusing or they are unsure about can be put to the side.

- Closed/mixed card sort: Tell the participants you are Explain that you are looking to understand how all of the items on the cards relate to each other. Explain that they can group the information in a way that makes the most sense to them.

- Open card sort: Tell the participant that you are trying to understand what should be in your product/service. Then explain, once they’ve finished naming the cards, that you want them to group the cards in a way that makes sense to them. Once the cards are grouped, you will ask the participant to name the grouping. Then explain that you will ask for a name for each group of cards once the participant has arranged them.

- Request that the participant thinks aloud during the session, so you can fully understand their thought process behind their categorizations. If the participant struggles with thinking aloud, be sure to prompt them regularly

- Thank the participant, give them a chance to ask any questions, and provide your contact information. Be sure to mention the timeline for any incentive.

- Finally, email the participant within 24 hours to thank them for their participation in the study and with any incentive you had offered

Analysis

Once you finish the card, it is time to analyze it! To keep the length of this article reasonable, I will write a separate article on how to analyze your card sorting results, including some templates.

Recommended tools and resources

- Notecards and pens

- Trello

- Optimal workshop

- UXSort

For more engaging discussion, please sign up for the User Research Academy slack group! And check out User Research Academy for free resources.

Concepts, processes, and terminology — oh my!

The important terms and ideas to understand as a user researcher.

I recently ran a webinar on the topic of transitioning from academia to user research. A lot of my webinar focused on the importance of understanding the teams and business you will be working in as a user researcher. Although you can create a perfect portfolio piece in a silo, it is imperative to have the ability to relate to how an organization runs. I have spoken to many UX research recruiters and what they look for, in addition to user research skills, is how you would integrate into a team.

It is challenging to demonstrate how you would fit into a team without a general understanding of the basics of how tech teams work. And without the jargon or terminologies that are common in the tech and user research industries. I recommend doing research on how tech teams work, how businesses work, and how user research can fit into organizations. This will make you stand out to recruiters and companies, as someone with a real passion and motivation to go above and beyond.

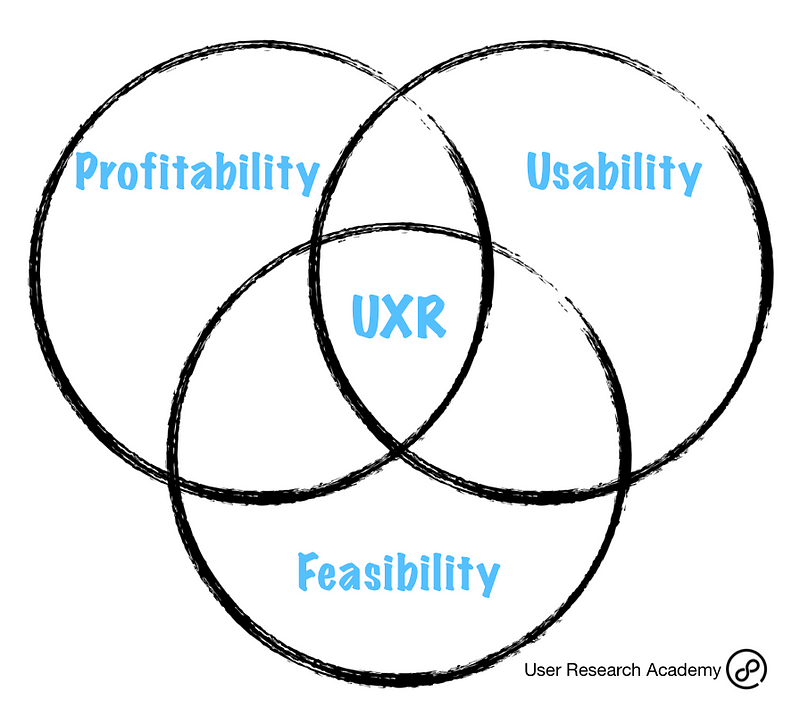

A note about business and user research

The real truth of the matter is that companies exist to make money. I hate always coming back to this fact, but it is reality. And we have to face reality. The majority of what teams are looking to accomplish in an organization exists to make that company money. We need to be okay with this fact and understand where user researchers fit into it.

User research enables teams to make the best decisions. When organizations make better decisions, it tends to impact essential business metrics for a company, such as conversion rate, revenue, retention rate, acquisition rate. When teams make informed decisions that create a positive impact on users, they can better contribute to the mission of making the company more money. So teams rely on you for fast research to make these better decisions and positively impact the organization as a whole.

This is really important to understand because it gives you context into what your mission is on a team, and in a larger organization, outside of the day-to-day tasks.

Now on to teams…

Fitting into a team is essential for user researchers. It is crucial to understand every single role you will be working with. These internal stakeholders will become your internal users. They will be reaching out to you with questions and digesting the research you deliver. By understanding what they are trying to accomplish, you can better empathize with them and tailor research insights in a way that is optimized for their day-to-day. This also helps you figure out where and when user research is relevant in a project.

Ideally, as a user researcher, you work with all different roles and departments. However, the colleagues I have worked with the most are:

- UX/UI Designers

- Product Managers

- Developers

- VP- or C-Level Executives (from Product, Engineering, & others)

- Account Managers

- Customer Support

- Content marketing

The list could go on, but these are the major roles I have seen could benefit from user research. Take the time to learn what each of these people does and what they are trying to achieve. With this knowledge, you can positively impact their lives with research, which will lessen the need to beg them for buy-in.

Processes, Jargon, and Terminology

I will not go in-depth with each piece of jargon, terminology, and process, but will provide a list of which you can use to then deep dive into. This also does not include every process, piece of jargon, or terminology out there, but it is a starting point for learning about the different concepts user researchers commonly encounter.

Processes:

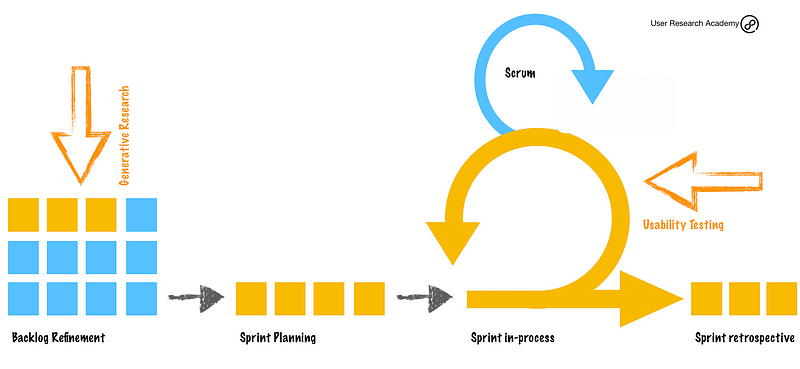

By understanding processes, you can understand where user research fits in.

- Agile

- Scrum

- Sprints

- Ceremonies

- Retrospectives

- Backlogs

- Standups

- Kick-offs

- Lean methodologies

- Waterfall

- Kanban

- Requirements

- Product management

- Product roadmaps

Concepts:

By knowing these concepts, you can make sure you are including them and doing robust research

- Business metrics (ex: click-thru rate, conversion rate, retention rate)

- OKRs / KPIs

- Product analytics, by using tools such as Google Analytics and Firebase

- Validating/disproving hypotheses

- Prototypes, wireframes

- ResearchOps

- Usability Metrics

- A/B testing

- Workshop moderation/facilitation

- Iteration

- Ideation

- Design thinking

- Recruitment

- QA (quality assurance)

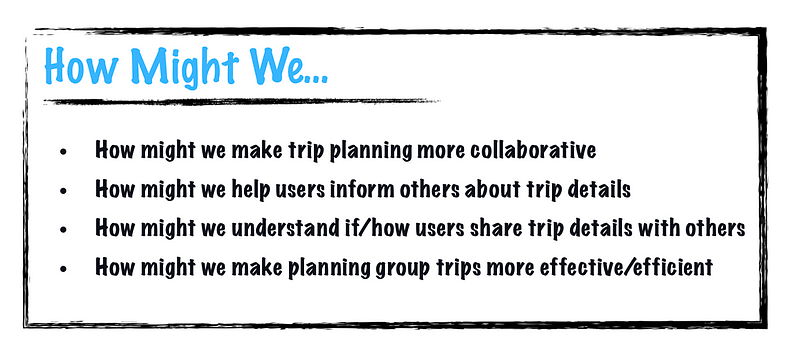

- How Might We Statements/reframing solutions

Terminology & Jargon

With knowledge of terminology and jargon, you can talk more confidently with many different departments about all you can help them with

- Generative research (or discovery research, problem-space research)

- Usability testing

- Diary studies

- Card sorting

- Guerrilla research

- Jobs to be Done

- Heuristic evaluation

- Competitive analysis

- Affinity diagrams

- Participatory design

- Mind map

- Customer journey map

- Mental models

- Empathy map

- User scenarios

- Surveys

- Screener surveys (link coming)

- Personas (and here)

- User stories

- Implementation

- Deployment

- JIRA

I hope these are helpful in getting you started with learning how tech and product teams/organizations work in the real world, as well as important terms to understand as a user researcher. The more familiar you are with these, the more you can conjecture how you could impact an organization as user researcher.

Especially big thanks to Nielsen Norman Group and Atlassian for documenting so many of these terms, making my life easier when finding great links!

If you are interested, check out more free content and my offerings on www.userresearchacademy.com and join our slack channel

If you liked this article, you may also enjoy:

User Research practice problems — updated

Because practicing whiteboarding, research plans, survey writing, and portfolio pieces makes perfect.

Updated March 2020

After teaching many classes and mentoring many students, the mantra “practice makes perfect” has become one of my most common sayings. During my courses and mentoring sessions, I only have so much time to go through practice examples. With that limitation, I thought it might be helpful to brainstorm a list of problems that many people can use to practice.

After teaching many classes and mentoring many students, the mantra “practice makes perfect” has become one of my most common sayings. During my courses and mentoring sessions, I only have so much time to go through practice examples. With that limitation, I thought it might be helpful to brainstorm a list of problems that many people can use to practice.

Some of the problems on this list are from my brain, and others from various things I may have seen over the internet. I’m sure some people have imagined these problems before me, and I will do my best to link to anything I take directly from another website. I will include these resources at the bottom of the article.

I will do my best to update this with new problems as much as possible. If you have any suggestions, please email me: nikki@userresearchacademy.com

How to use the list

The reason I put this list together is so you can practice various skills:

- Whiteboarding sessions (read how to tackle a whiteboard session)

- Writing research plans (read more about research plans, with a template)

- Survey writing (read about writing survey questions)

- Research portfolio pieces (how I structure a user research portfolio)

And anything else you think about!

You won’t have all the answers since these are static problems, and I can’t answer all the questions you may have about each problem. I also didn’t go into crazy detail for each problem. In this case, write down the questions you have or the assumptions you make. And then how you would tackle these. This is good practice regardless, as this happens a lot in real life!

Now on to the problems…

List of practice problems:

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people travel?

Project brief:

Your client is a leading travel brand who sees new opportunities emerging in the digital space around how people plan travel. They want you to focus your research on one group of the travel experience, either leisure travel or business travel. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people travel, in order to start designing something relevant for users.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people adopt a pet?

Project brief:

Your client is a non-profit animal shelter who wants to better understand the process people go through when trying to adopt a new pet, specifically in the digital space. They want you to focus your research on people who have adopted a pet in the past 1–2 years. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people adopt pets, in order to start designing a digital solution relevant to users.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people digitally communicate with each other?

Project brief:

Your client is a messaging platform that wants to better understand how people digitally communicatee with each other. They want you to focus your research on people who use platforms such as iMessage, WhatsApp and Facebook Messanger to communicate with others on a daily basis. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people communicate with each other, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people find their way around a new city?

Project brief:

Your client is a tourist agency who wants to better understand how people find their way around a new city. They want you to focus your research on people who have traveled, at least once, to a new city in the past six months. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people navigate a new city, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people organize their wardrobe?

Project brief:

Your client is a retail platform that want to better understand how people organize their wardrobe. They want you to focus your research on people who purchase new clothing on a regular basis (at least once a month) and care about organizing their wardrobe. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people organize their wardrobe, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people set and stick to their goals?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people set and stick to their goals. They want you to focus your research on people who have set a goal in the past six months and have either followed it through or have not been able to complete the goal. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people set and stick to their goals, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people keep up to date on the weather?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people stay up-to-date with the weather. They want you to focus your research on people who currently use weather apps, or listen to the weather channel. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people stay up-to-date with the weather, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how to make women feel safe when traveling alone?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how women currently travel alone, and the concerns they have. They want you to focus your research on women who have traveled alone at least once in the past six months. The client expects you to deliver insights on women traveling alone, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people order food takeaway online?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people order food takeaway online. They want you to focus your research on people who have ordered food online at least three times in the past month. The client expects you to deliver insights on online food ordering, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people decide and plan to move?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people decide to and plan to move. They want you to focus your research on people who have moved to a new house or apartment in the past six months. The client expects you to deliver insights about moving, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how to reduce homelessness in major cities?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how to reduce homelessness in major cities. They want you to focus your research on major cities that are dealing with a homelessness crisis (ex: NYC, LA, SF). The client expects you to deliver insights about how to reduce homelessness, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people find and keep roommates?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people find and keep roommates. They want you to focus your research on either someone who has just found a new roommate, or people who have been roommates for more than one year. The client expects you to deliver insights about how people find and keep roommates, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people recycle?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people choose and understand recycling. They want you to focus your research on either people who have recycled consistently over the past six months or people who have tried recycling and gave up. The client expects you to deliver insights about how people choose and understand recycling, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people buy clothes online?

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people choose and buy clothes online. They want you to focus your research on people who have bought clothes online at least five times over the past six months and have returned at least three items. The client expects you to deliver insights about how people buy clothes online, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Problem statement

How can we better understand how people respond to and gather information about a pandemic? (COVID-19 bonus!)

Project brief:

Your client wants to better understand how people respond to a pandemic. They want you to focus your research on people who have lived through a pandemic and have experienced a lockdown/quarantine during that pandemic. The client expects you to deliver insights about how people respond to and gather information about a pandemic, in order to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

Resources

- 100 Example UX Problems by Jon Crabb

- 100 Days of Product Design by Susan Rits Design LLC

- Designercize by Mezzotent

- WeWork Interview Exercises

If you are interested, check out more free content and my offerings on www.userresearchacademy.com and join our slack channel

Which UX Research methodology should you use? [Chart included]

Start with this question, and all else will follow.

When I first started as a user researcher, I believed there were two types of user research: usability testing and discovery research. I was right, those two types of research do exist, but they are not the only methodologies a user researcher can use to answer questions. But, alas, I was young in my career and believed every problem could get solved in one of these two ways. Am I needed to test a prototype? Usability testing. Am I required to figure out the content? Usability testing or discovery research (depending on my mood). Do I have to figure out how a user feels? Discovery research.

For a while, it was all very black and white. It was a simple time, and one where I believed I could unlock all the answers by using these two methods. I didn’t have to think about information architecture, long-term studies, testing concepts, surveys, clickstreams, A/B testing, the list goes on. Sigh, it was an effortless time.

However, like most people on their career path, I finally hit a wall. I encountered a research question I could not solve with these methods, despite my trying. I did try, and I failed miserably at this.

We were trying to redesign the navigation of our platform and where different features appeared on each page. Notice, we didn’t start with a problem statement or a goal. We started with a solution of a redesign. Also, we already had the redesigned screens. With this in mind, I figured a usability test could solve all of our problems, or validate our pre-defined solutions.

In the end, we decided to do a usability test with the new navigation and layouts. It was clunky, but our participants got through. However, when we released the changes (not too far after the user tests), we found a lot of issues and had to revert to the old designs.

So what could we have done better?

There were many things we could have done better, but I’ll focus on the three biggest ones we could have changed:

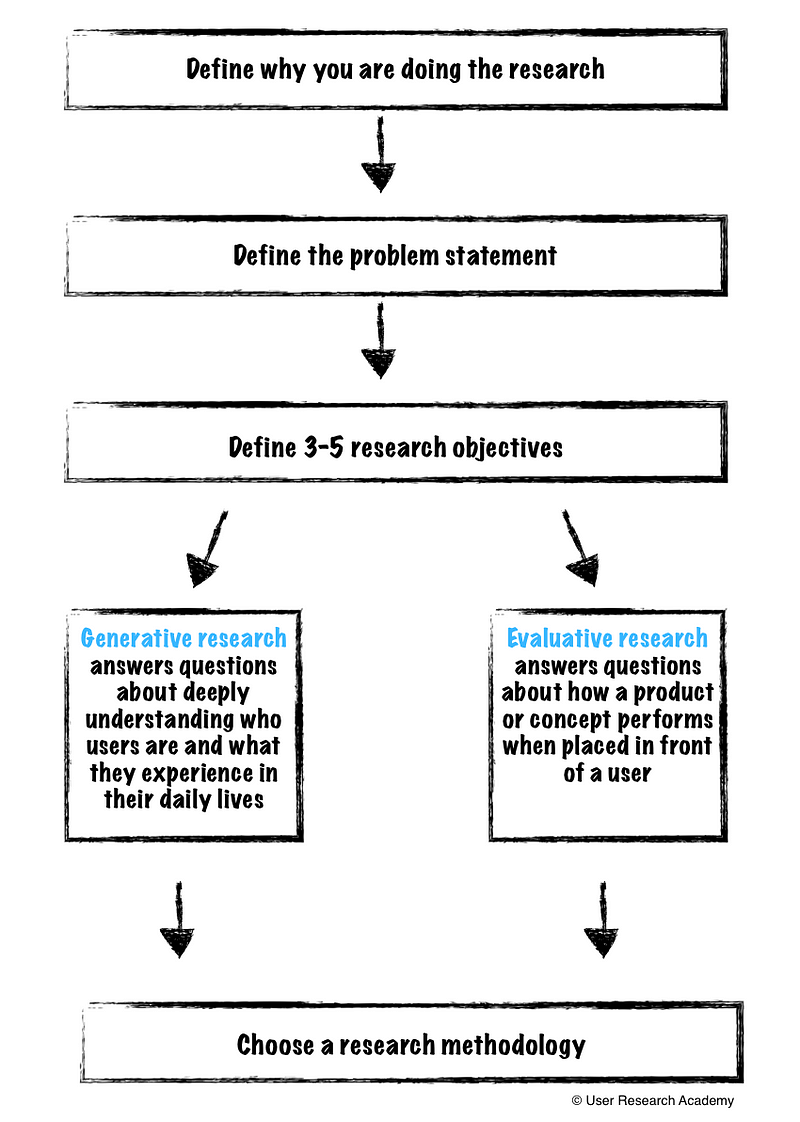

- Define why. Defining the why is step one of any research project or initiative. We have to understand why we are doing the research. I often include the why from the user perspective, as well as the business perspective. The why can be a simple paragraph explaining the reasoning behind the project.

- Start with a problem statement. When you start any user research project, it is essential, to begin with a problem statement. A problem statement is a central question that has to be answered by the research findings. In this case, we started with a solution, which led us down the wrong path. By starting with a problem, you are much more likely to solve an actual user need. Learn more about reframing a solution to a problem statement.

- Consider the objectives. By starting with goals, we can understand what we are expecting to learn from the research. We can ask ourselves what we are trying to learn and what we would like the research to achieve. Objectives keep your research on track and align everyone with an expected outcome. Learn more about writing objectives.

Since we skipped straight to testing a solution, we missed these crucial steps. By doing this, we ended up with a suboptimal experience for our users because we didn’t understand what their problems were and what they needed. It is an easy trap to fall into, but easy to avoid by following those steps. Instead, the process should have looked much more like this:

Defining the basics

With the knowledge from above, the outcome of that research project would have been much different. However, I still had the idea that there were only two types of user research: usability testing or user interviews. If only I could have told myself about all the different methodologies out there. Instead of time traveling, I will rewrite history to showcase the process I would go through today to choose a method for the same project.

The project was: Redesigning our hotel concierge platform navigation and information architecture of our features for hotel concierge.

Step 1 — Define why you are doing the research.

We have seen some users struggling when trying to navigate through our platform. Through user research, we have observed users hitting the cmd+f option to find what they are looking for to make the process faster. They are unable to find nested information as they are not sure where to look in our navigation. Also, users have been employing several hacks as opposed to using the features we have built.

Step 2 — Define a problem statement.

I am a hotel employee trying to fulfill a request for more towels for a guest, but I am unable to find that specific feature, which makes me feel frustrated. With this, I have to enter a generic request, and then write in what I specifically need and hope someone reads my notes.

Step 3 — Define the objectives.

- Understand the general workflow of users and when they need access to particular pages/features

- Discover how users are currently using the product

- Uncover the limitations and pain points users are facing in different situations with the platform

- Learn about any potential improvements in workflow, information architecture, or missing features

Choosing between generative and evaluative research

Now here is where things became fuzzy, and where I want to dive deeper. Although now I have a good understanding of which methodologies would have been best for answering the question and objectives, it didn’t always come so intuitively.

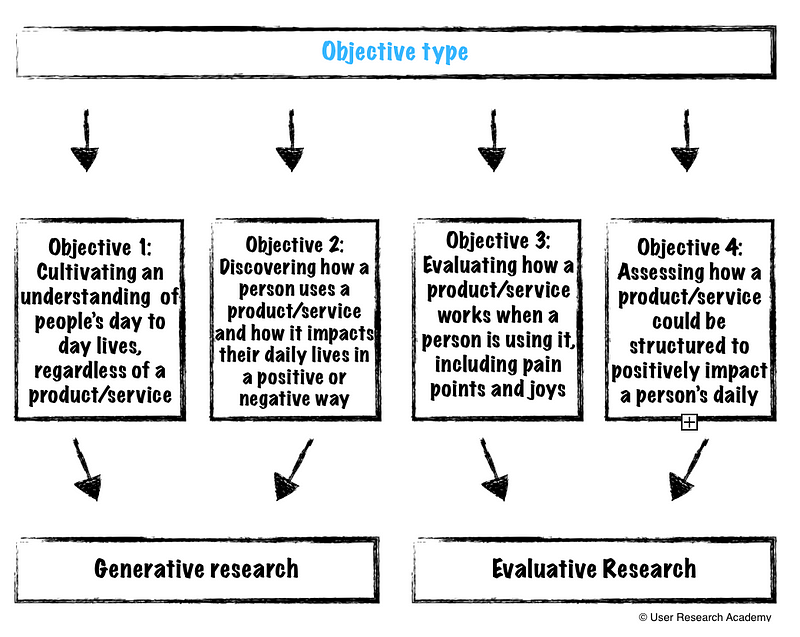

Since then, I have seen four significant types of objectives:

- Understanding more deeply about people’s day-to-day lives, regardless of a product/service

- Discovering how a person uses a product/service and how that product/service impacts their daily lives (positively and negatively)

- Evaluating how a product/service works when a person is using it (pain points and joys)

- Assessing how a product/service could be structured to impact a person’s daily life positively

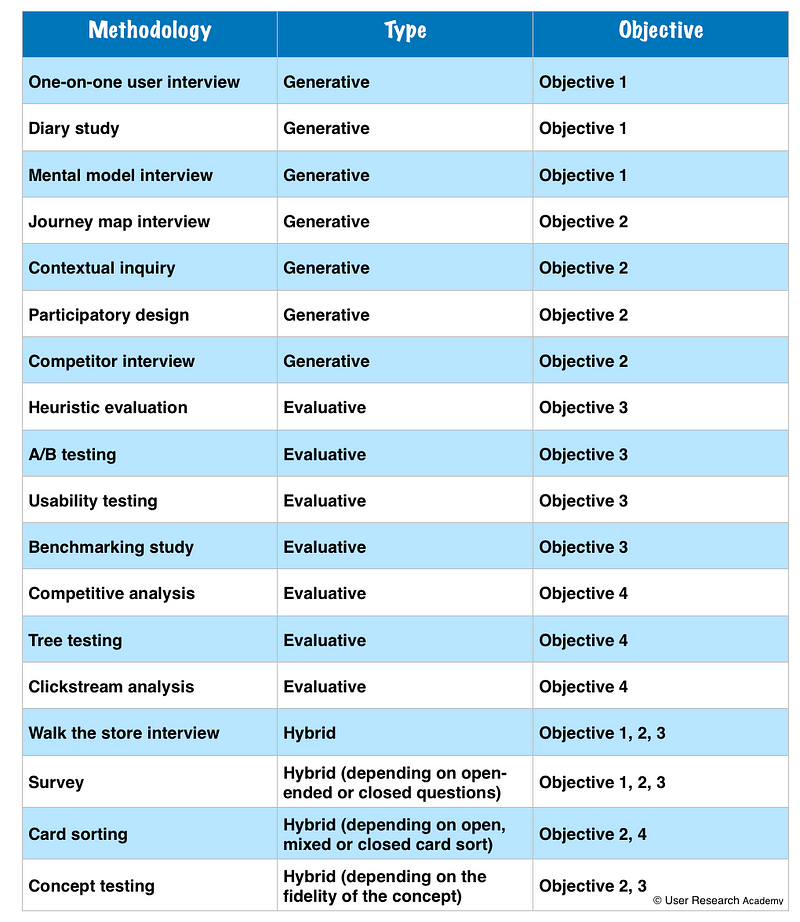

By breaking these objectives down, we can then choose between generative research and evaluative research.

- Generative research allows a deep understanding of who our users are (inside and outside of a product/service). We can learn what they experience in their everyday lives. It allows us to see users as human, beyond their interaction with a product/service.

- Evaluative research is about assessing how a product/service works when placed in front of a user. It isn’t merely about functionality, but also about findability, efficiency, and the emotions associated with using the product/service. Many people think evaluative research = usability testing, but it goes much further than that

- Hybrid research is a combination of generative research and evaluative research. The example I’ve used above can very well end up being a hybrid method. Hybrid research helps us simultaneously understand our users, as well as how a product/service is performing. Now, this is not magic and, since it covers both spaces at once, it does not go as deeply into a place of understanding or evaluation. I will focus on hybrid research in a future article, as it is a more advanced technique.

Once we understand what type of research we are looking to conduct, we can better understand which methodology ties best to our objectives. I have included a chart of methods I have used, and how they relate to the above goals I have realized.

If you are curious, for the research project I mentioned above, I would have suggested the following methods:

- Contextual inquiry

- Walk the store interview

- Card sorting

Now, none of this is an exact science, and your opinions may differ on this, which is fantastic! I would love to hear about how you approach this differently.

Interested in more user research? I teach an Introduction to User Research Course and am available for one-on-one mentoring. Check out the User Research Academy. Please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions

5 ways to reframe a solution to a problem statement

And why this is essential for user research.

Very rarely do I get handed a problem statement. Whenever colleagues want to engage with me in a research project, they have already landed at a solution. I am not saying this is bad because solutions are a comfortable place to start. They are easy. However, they limit our potential and possibilities. I’ll give an example of something I hear frequently:

“We want to build a share feature for our users so they can share their trip ideas or details to friends and family. Can you research this for me?”

I’m sure this statement resonates with many user researchers. It is a tough situation to be in, and one that happens far too often. If this is the type of statement you are consistently getting from colleagues, you have an excellent opportunity to teach a new mindset. You can teach the mentality of approaching ideas from the problem-space before solution-space.

Why is reframing the solution important?

I’m going to pick on Google, for once, because I believe Google has enough self-confidence to take a small hit. Let’s talk about Google Glass.

To be upfront, Google Glass was a failure. The product did not succeed in the slightest. There are several different reasons for the flop, but we will focus on one in particular: Google Glass did not solve a problem for users.

There were many assumptions made about Google Glass, which were not validated with users. The conjectures led to many questions and, ultimately, to a product that did not correlate with the user’s needs or goals. There was a lack of clarity on:

- Who would use Google Glass

- When/where people would use Google Glass

- Why people would use Google Glass

- What value Google Glass brought to people

These are a lot of essential questions that were left unanswered. With this approach, there is a substantial likelihood that products will fail. If there is no value to users, they won’t use it.

And the best way to determine value? Start with a problem, not with a solution.

By understanding the problem-space before coming up with a solution, we allow for:

- Understanding a user’s actual problem and need

- Brainstorming ideas that are relevant for users

- More possibilities to help with a particular problem

- A higher likelihood of a successful product/feature

The best way to understand the problem space is by conducting generative research sessions with users. Although I won’t cover generative research here, please take a look at my comprehensive guide to generative research.

Picking apart the solution

We’ve established how important it is to start with a problem rather than a solution. However, many times, we are faced with a solution, as in the first example. Let’s take a look at that again:

“We want to build a share feature for our users so they can share their trip ideas or details to friends and family.”

Let’s assume there has not been any user research done on this topic of “sharing.” There are a few things that are not ideal with this statement:

- There is no clarity on what the problem is we are trying to solve

- We jump directly into a solution

- Users wanting to share their trip ideas or details is an assumption

- Sharing might not be the only or best solution

- Our thoughts should come from generative research

But, lets base this scenario in reality. We’ve received this solution and need to test it. We can go in one of two directions:

- Usability or concept test the solution

- Take a step back and consider the problem

I know the latter isn’t always possible, which is why I included the first option. Sometimes the idea/feature/product is too far down the production line, and we have to do damage control. The best we can do is usability test the solution to understand what we can improve in further iterations.

However, sometimes it isn’t too late, and we can take a step back and consider the problem. We can ask the question: “what problem is this solution trying to solve?”

Tools to reframe the solution -> problem statement

This kind of question may be much easier for researchers to think about since we are used to doing this daily. For our colleagues, it might not come as naturally. Luckily, there are a few different methods we can employ to help us reframe the solution.

‘How Might We’ (HMW) Statements

This method is very trendy in the UX world, and for a good reason. ‘How Might We’ statements allow us to reframe our insights and thoughts into a broader context. We use these types of statements because they can get us thinking about the problem from many different angles, and they open the door to creativity. They also ensure we are thinking about an actual user need versus just coming up with cool ideas. Let’s take the sharing example and recontextualize it with HMW statements:

Investigative Stories

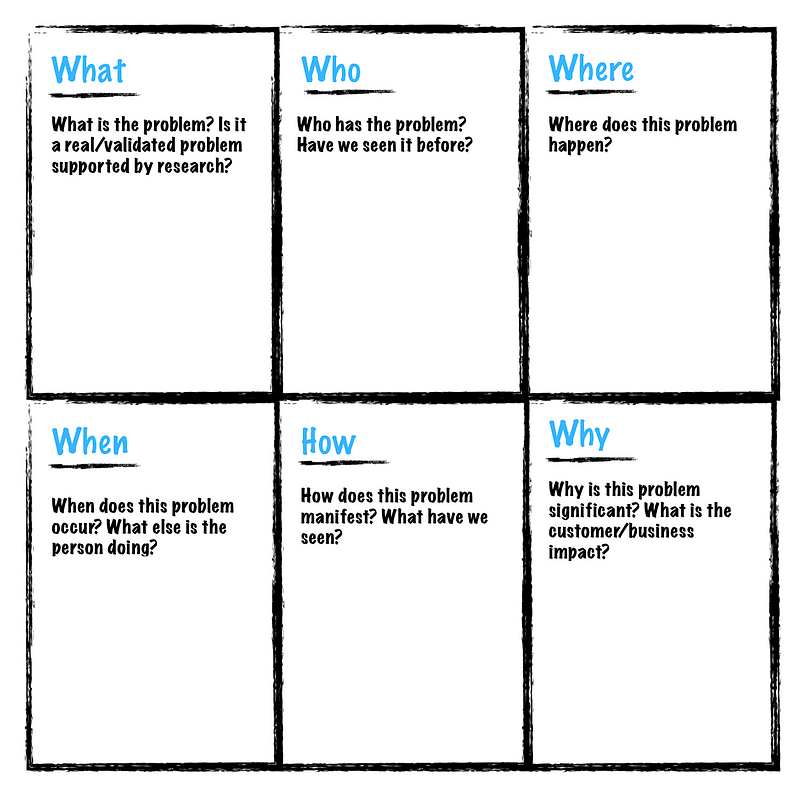

Investigative stories enable us to become detectives when thinking about a problem. With this method, you employ a journalist-type view of the situation. By looking into all of the different aspects of the problem, you can get a holistic picture of what you are trying to tackle. After you answer all of the questions, you can create a story of your user, which helps to understand the actual user need/problem.

Unpacking Assumptions

This is a technique I have been practicing and teaching for many years now. It is one of my favorites as it plays very well into my Buddhism practice. Before I begin thinking about solutions, I list all of the different assumptions I/we have about the user. It consists of everything you think you know. If we take the example above, the list might look like this:

- Users want to share trip details with friends and family

- Users are booking travel for a group of people

- Users need other’s opinions on their trip options/details

- Users find their current method of sharing details painful

- Users want a new way to share trip details with others

The Six Thinking Hats Model

Dr. Edward de Bono originally introduced the ‘Six Thinking Hats’ model. This method examines problems/concepts from many different viewpoints to get a holistic understanding. Getting colleagues to engage in this kind of exercise can be complicated, but also extremely rewarding. The thinking hats/roleplaying game gets people into the minds of users. Each person wears a hat:

- White hat: Facts

- What information do we have?

- What hasn’t worked in the past?

- What information is missing that we need?

- What are the weaknesses? - Green hat: Creativity

- What are the other angles we are missing?

- What are the alternatives?

- What are the next steps? - Yellow hat: Benefits

- What are all the benefits of the different options?

- What solutions would work?

- What is the best-case scenario (for users and the business)? - Black hat: Risk

- What are the different risks of each option?

- What solutions would not work?

- What is the worst-case scenario (for users and the business)? - Red hat: Feelings

- How do the options make you feel (from the user’s perspective)?

- What do you like about the options?

- What don’t you like about the options? - Blue hat: Process

- Where are we now?

- What other work needs to be done?

- What is the next step?

Research Plan Template

One of the most significant pieces of advice I can give is to create a template that prompts colleagues to think of the problem statement before they even come to you. An additional way I do this is by sending a research plan template for colleagues to fill out before we meet to discuss features. This template starts with the problem we are trying to tackle, rather than the solution. With this, you can start discussions from the problem-space. Check out my research plan template.

Writing the problem statement

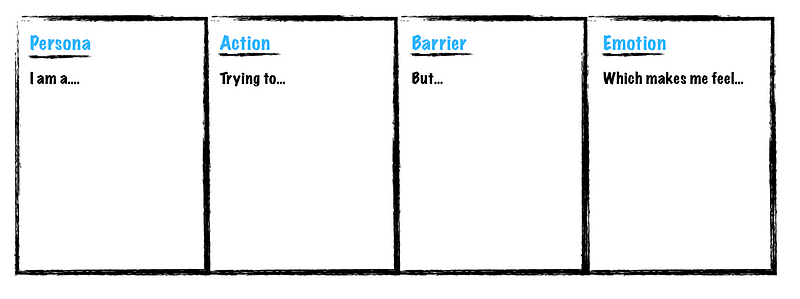

Once you have done these exercises, you can write some problem statements. I mentioned the ‘How Might We’ formula above, but I also use some other problem statement formulas:

- I am (persona/role) trying to (do X) but (barrier/problem) because (x), which makes me feel (emotion)

- I am a mom trying to book a flight ticket home for my daughter, but I don’t know her college schedule, so I am unsure which dates to book for her, which makes me feel frustrated.

- I am (a persona/in a situation) who needs a way to (user need) because (current problem)

- I am traveling with a group of friends and need a way to coordinate everyone’s schedules so that I can pick the best date/time for everyone

You don’t have to use the exact formula (I deviated above), but it is an excellent framework to keep in mind. Try to avoid proposing solutions during this phase, as it is an easy trap to fall into. Keep your focus on the problem and facts.

Overall, getting people to shift from the solution-space to the problem-space is a considerable challenge, but one worth confronting. If you are continually urging others to think about the problem before the solution, they will start to adapt to that mindset. By instilling these practices, and with some time, you can transform the mindset of an organization to approach ideas from the problem-space. Not only does this make your life as a user researcher easier, but it also turns the company into a much more user-centric culture.

If you liked this article, you may also find these interesting:

- User Research isn’t black & white

- How to write a generative research interview guide

- Benefits of internal user research

- User research plans — with template

Interested in more user research? I teach an Introduction to User Research Course and am available for one-on-one mentoring. Check out the User Research Academy.

Please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions

Is it time we move beyond the NPS to measure user experience?

Why the NPS sucks and what to use instead.

I get an overwhelming sense of grief and anger when I see the Net Promoter Score (NPS) being used as a beacon of light for companies. I have heard so many people praising the NPS, and using it as a legitimate way to measure customer satisfaction and success of a company. In fact, sometimes, it is used as the only way to measure these metrics. But, I really believe, the NPS should not be the basis of making critical decisions.

As user experience and user research gain traction in the tech/product field, there are so many additional ways to gather feedback, measure satisfaction, and pinpoint where you are disappointing your users. The NPS feels like a very archaic metric that stuck around simply because it is easy. And, to be honest, the other suggested metrics in this article are more difficult than the NPS, but there is a reason behind that.

What exactly is the NPS?

If you have ever tried out a product or service, you have probably seen this question before:

On a scale of 0–10 how likely are you to recommend <product or service> to a friend or colleague?

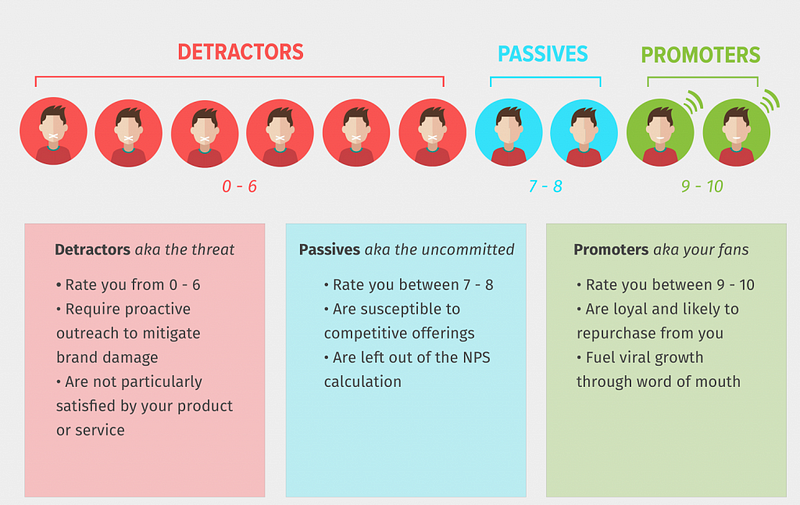

Your NPS is the accumulation of people who use your product or service taking the time to rate whether or not they would recommend your product or service to others. Based on the score they give your product or service, they fall into one of three buckets:

With this information, you are able to calculate a score that you can measure across time. The formula to calculate the score is:

Net Promoter Score = % of Promoter respondents minus % of Detractor respondents

Remember, passives are kept out of calculations, so any scores of 7–8 essentially do not exist in terms of scoring.

As an example, let's say you received 100 responses to your survey:

- 40 responses were in the 0–6 range (Detractors)

- 30 responses were in the 7–8 range (Passives)

- 30 responses were in the 9–10 range (Promoters)

When you calculate the percentages for each group, you get 40%, 30%, and 30%.

To finish up, subtract 40% (Detractors) from 30% (Promoters), which equals -10%. Since the Net Promoter Score is always shown as a number (not percentage), your NPS is -10. NPS scores can range from -100 to +100.

In addition, the NPS appears to do things that other business metrics don’t or can’t. It is:

- A single question that is easy to understand

- Easy to calculate and measure

- Easy to track any changes over time

- Widely accepted in business

Why the NPS is a suboptimal metric

There are a few reasons why I think NPS is not the most ideal metric to use as a single metric. I am in no way saying, “never use the NPS again!” If you want to continue measuring NPS, just understand what you are really measuring and consider additional metrics to track alongside the NPS.

- Why is recommendation a sign of satisfaction? There are so many different reasons why one might or might not recommend a product/service to a family member, friend, or colleague. Sure, we could assume the mental model of “I am satisfied with this product/service, therefore I would recommend it,” but this still leaves many situations unanswered. What if it simply doesn’t make sense to recommend the product/service to these people because they never use anything like this? Or maybe you are unsure about the value since you haven’t used it a lot. Maybe you hate it, but someone else in your life would benefit from the product/service. There are many different contributing factors to recommendations, and they don’t always lead to product success and customer satisfaction

- Recommendations are contextual and subjective. Similar to the above statement, whether or not someone gives a recommendation can be completely subjective and based on context. Would I recommend a movie I just saw to others? Maybe. It depends on the person. If it was a comedy, I would potentially recommend it to my friends who like comedy, but not my friends who like action or thrillers. I could have also had a terrible night with bad popcorn, and lumpy theater seats, causing me to dislike the movie because of circumstance, rather than quality. Or I could have simply been having a bad day, and that impacted the experience I had with a product/service, causing me to give a bad score. There is a multitude of reasons why recommendations are extremely contextual and subjective