A comprehensive (and ever-growing) list of user research tools

Everyone in the UX field (and tech/product, in general) seems to really love tools. We all want tools to make our lives, and jobs, easier. We strive to find tools to solve the most common problems we face. There is a good amount of information out there on different tools, but I haven’t come across a comprehensive list dedicated to user researchers (other people in the UX/product field can also benefit)!

As researchers, we have a lot of different components to our job that we then have to bring together into a presentable and actionable insight we can present to our teams. With this, they can go out and make products better.

I have broken up the different resources into different areas/responsibilities of user researchers. A lot of these tools may overlap and make sense in different areas, but I wanted to try to separate them as best as I could. I will highlight some of my favorites and will link to everything I can. As time goes on, I hope this list only grows. Please comment with your favorite tools or recommendations!

User Research Tools

Slack Channels:

I wanted to start off with different slack channels I have found extremely helpful as a user researcher. These channels span across the world and offer information on jobs, resources, different discussions on research methodologies and more

- Mixed Methods

- Research Ops

- HexagonUX (all women)

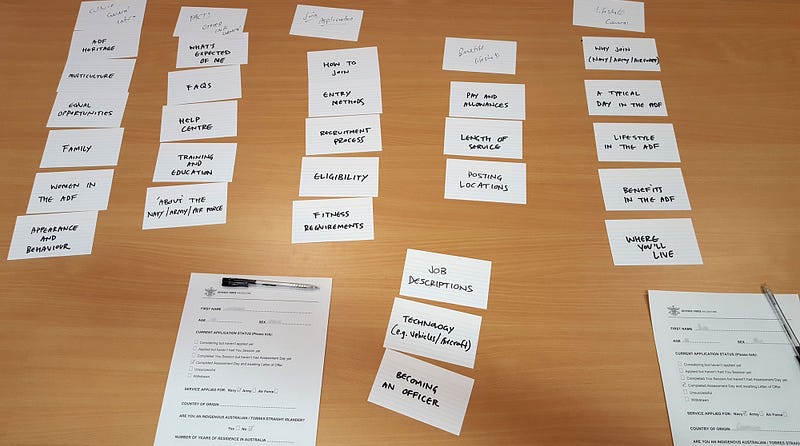

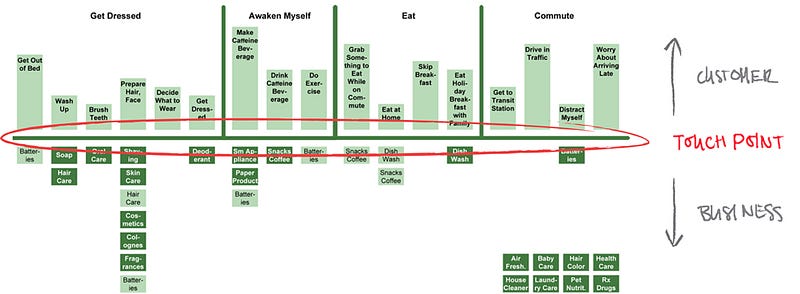

UX Artifact Templates:

Honestly, Pinterest (follow my user research board) is a great way to find templates of UX artifacts, which can help non-designers get a little more creative when pulling together research. I have highlighted some of my favorite tools, and also some I have created myself. All of these are templates. You don’t have to follow them exactly, but they may give you ideas on how to visualize the research you have done.

- XMind (for mind mapping)

- Mini Heuristic Evaluation

- Empathy Map Template

- Persona Template (from UX Lady)

- Customer Journey Template 1

- Customer Journey Template 2 (scroll down — includes a Service Blueprint, too)

- Scenario Storyboard Template

Competitive analysis:

Competitive analysis may not be in every user researcher’s job description, but it is a good idea for you to properly understand the competition in the space. I have created both of these templates. The first is a much more high-level understanding of competitors, while the second dives much deeper into the details.

- SWOT Analysis Template

- Competitive Audit Template

Research Platforms/Databases:

Below are some options I have used before for platforms to recruit, conduct and organize research. Some tools have different abilities than others, but they are all fairly robust. One of my favorite tools for conducting remote card sorting or IA sessions is Optimal Workshop. They do a really great job with set up and post-research analysis. I also think Usabilla is a great tool for getting users to engage with quick surveys or research opt-ins.

- Optimal Workshop (including Optimal sort, Treejack and First Click Testing)

- Usabilla

- Uservoice

- Userzoom

- Validately

- Airtable

- Nom Nom

- dscout

Research Artifact Templates:

I have created a few templates to showcase what, in general, goes into a research plan and research report.

- Research Plan Template

- Usability Testing Plan Template

- Research Report Template

- UX Research Portfolio

- Usability Testing Metrics Spreadsheet

Recruiting:

I know I have already mentioned a few platforms above that are able to help you recruit participants, but I wanted to make a separate list for those I have used almost solely for the purpose of recruiting. If you are looking to recruit in the US, UserTesting is definitely a favorite and, for Europe, I would pick TestingTime.

- TestingTime

- UserTesting

- Ethnio

- Userzoom

Prototyping:

We may not need to make wireframes and design UX/UI, but we still need to work with designers on both of the above. My absolute favorite tools either for working with designers, or for when I need to create my own designs, are Sketch & Invision. The combination is wonderful and fairly fluid. This makes testing prototypes during usability tests easier. I also want to give a shoutout to Pop (by Marvel) for bringing paper prototypes to life, definitely worth a try!

- Sketch

- Invision

- Balsamiq

- Zeplin

- Proto.io

- Pop Paper Prototyping

- Framer (Sketch competitor)

Synthesis & Sharing:

Synthesizing and sharing results can be really difficult, both in-person and when your team is remote. Some of the above solutions in the research platform list (ex: Airtable) help with this. Below are separate tools I have found to help run synthesis sessions and share research results. My absolute favorite tool on this list is Mural.co, they have allowed me to easily hold remote synthesis sessions with teams across the world. My other favorite, for sharing, is Mosaiq, a customizable wordpress site. I have also showcased an example of a usability testing spreadsheet where I use the stop-light method.

- Post-its for affinity diagrams (because what research article would be complete without them)

- Mural.co (for remote synthesis)

- Aurelius

- Mosaiq

- Usability Testing Spreadsheet

- Notion

Notetaking & Transcription:

I haven’t come across many notetaking apps that are more effective than using excel, word, or getting your research sessions transcribed. The one that also offers analysis of your notes in Reframer. I used it briefly, but I am too in love with my way of taking notes on excel to move to a different tool. I have used very small transcription services in the past, but I have heard good reviews from these companies.

- Reframer (notetaking by Optimal Workshop)

- GoTranscript (transcription by humans)

- Temi (AI transcription)

Surveys:

There are many platforms that allow you to set up surveys, all with different capabilities. One of my favorites is Qualtrics, as it allows for some really nice question logic, and has some great analytics tools. If your budget isn’t there for surveying tools, something as simple as SurveyMonkey, GoogleForms or a Microsoft Word document can also be effective.

- Qualtrics

- QuestionPro

- LimeSurvey

- Typeform

- Sample Screener Survey Template (Microsoft Word)

Analysis (of Behavior):

Having a platform or tool that helps analyze user’s behavior on your app or website can be extremely helpful when pulling examples for research insights. If you don’t mind being creepy, FullStory or Hotjar are great tools that record sessions of users on your product, and allows you to watch them either live or later on. I have also found HotJar to be useful when trying to justify information hierarchy via heatmaps.

- Hotjar

- Optimizely

- FullStory

- Bugsee (mobile)

- Appsee (mobile)

Remote usability testing/interviewing:

Earlier I mentioned some robust research platforms and recruiting tools, that also allow you to conduct interviews on the platforms, but I wanted to highlight a few tools in particular that are useful for remote usability testing or interviewing. My absolute favorite screensharing and video conference is Zoom, as it has many capabilities and is extremely reliable.

- Lookback

- Zoom

- Google Hangouts

- Userzoom

- UserTesting.com

Surveys

There are many usability surveys floating around out in the space of the internet. I have a folder that includes some of the top surveys, such as the SUS, QUIS and USE.

All of these recommendations and opinions are 100% mine, no sponsorship here, I’m not that cool or popular. I will continue to add to this list as I explore other tools and also as I hear from you about what your favorite tools are. Please drop a line to help this list grow and expand into a resource for all to use!

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

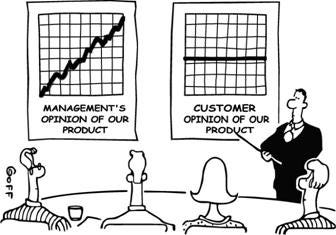

“We don’t need user research…”

The ability to convince stakeholders they need user research seems to be a more important job requirement than the actual ability to conduct research sessions.

I once had someone approach me and say, “you know what, user research is overrated.” This person knew I was a user researcher. I no longer talk to this person (not because of what they said in that instance, but their general attitude towards life).

Even though user research is becoming more mainstream and popular, dare I say it’s “trending,” there are still many challenges faced when thinking about implementing a user research practice into a company. The most common is getting buy-in from (usually) higher-level stakeholders. The ability to convince stakeholders they need user research seems to be a more important job requirement than the actual ability to conduct research sessions.

I have worked at companies where user research wasn’t particularly valued — some to the point where I seriously considered why they hired me in the first place. It was difficult to consistently have to be fighting for research, fighting for what I did (or was meant to be doing) on a day-to-day basis. When someone comes up to you and tells you how unimportant user research is, it can be infuriating and really defeating.

Usually, what I have found, are there are common misconceptions about user research and the value it brings. Typically, people shy away from the amount of time user research can take. What they may not understand is user research can fit properly into sprints. It doesn’t have to take months! My favorite (and simultaneously least favorite) argument, however, is:

“We already know what our users want and need”

Now, this statement is tough. I can understand people’s rational fears of time, money, added value, and I can speak to those when I explain to them my plan for user research.What becomes more difficult, without research, is telling a higher-level executive they have no idea who their customers are and that they are wrong. For example:

Boss: “I think we should implement this new feature that makes customers rate our products they just bought before being able to browse new products.”

UR: “Why do you want that?”

Boss: “Because we can get more ratings on our product and make it more obvious how to rate.”

UR: “But how would that make for a better experience for our customers?”

Boss: “I’ve worked here for quite some time, I know what our users want. I think they’ll love it.”

UR: “ But how do you know they will love it? Based on my previous research projects, I’m not sure if they would. Maybe we should test this?”

Boss: “We don’t need to test it, that would be a waste of time. I know it’s a good idea, so that’s what we will do.”

This may be an extreme example (or maybe not), and I have definitely heard it before. You could argue the time issue here, but I doubt that is actually a concern. The most concerning part of this is the implementation of a feature without the thought of research (generative or evaluative), based on the fact that someone who has been working at the company, or in the industry, for some time just knows. When you have the opportunity to so research, it is best to choose that path rather than making the gut decisions.

So, here we are, talking about how we are going to implement a horrible new feature that will, most likely, dissatisfy or annoy our customers. As a user researcher, this is tough and we have all been here. I will ask two questions: why is this happening? What can we do to solve this?

Why is this happening?

This boss is a person who is trying to make the best decisions based on the information they have in front of them — which is their experience and understanding of the customer, regardless of how right/wrong that is. The answer may seem illogical, but this response of “I know what is best” is a fall back tactic when you don’t have the time to explain your rationale. This rationale might be something you are familiar with or it might be something completely outside your mind, such as “the CEO said this” or “I need to hit X numbers by a certain date” or “I saw data that said this was a good idea.” Just because they are thinking this, doesn’t mean they will explicitly state their reasoning. In addition, the boss is probably interacting with many people during the day, who are saying what decisions should be made and giving their own opinions on situations. Out of all those people, you are only one voice.

What can you do?

Most of the time, I would like to prove the boss wrong and to show them actual user research that disproves their hypothesis. I want to push the research. I want customers to be happy. What if, instead, we try methods that give the boss more tangible solutions rather than “we need to research that.”

Boss: “Implement this rating feature!”

UR: “What an interesting idea. I’d love to run it through our research process, where we test next features to make sure users value them, and they work with our current product. We do this to make sure customer satisfaction, acquisition and growth metrics stay high. By testing any changes before implementing them, we are able to know that we are iterating towards success, keeping business KPIs up, and not just making changes because someone has a feeling”

Or

UR: “That would be a great addition to the test we are running this week. I’ll make sure to send you the results as soon as we have them in about two weeks, so you can use them for further conversations.”

Or

UR: “Have we done previous research on the benefits of that feature?”

Boss: “No”

UR: “Let’s put a prototype together in the next few days. We can go out and guerrilla test it with our users — I would love it if you could join us.”

Or

UR: “Let me talk to the team and come up with some potential benefits of that feature, including how and when users would use it. Can I get that to you by the end of next week?”

Bottom line, offer a solution with a tangible artifact at the end, so the boss has something they can reference or use. Although it may sit in their back pocket, there is a much higher chance they will be more open to the discussion in the future if you give them something. Eventually it could turn into a more consistent and user-focused process.

Bosses are only as much of an antagonist as you make them. Tell them about the different actions you can immediately take to give them something real, and they may just take your side.

An aside

In one way, I will agree, there are certain times where user research doesn’t fit in, but I will tweak the saying a bit: you don’t need half-assed user research. This may be controversial. A lot of people may say, “any research is better than no research.” Sure, in theory, that is correct. When you need something, any of that thing is better than none of that thing. The difference, however, is that research can be done wrong. And it can go wrong fairly easily with those who may not have the proper understanding or training. Doing half-assed, improper research can actual hurt the company and prohibit them from finding a researcher, or someone knowledgable in user research to help them down the road. A now and a future problem.

Benchmarking in UX research

Test how a website or app is progressing over time.

Many user researchers, especially those who focus on qualitative methods, are often asked about quantifying the user experience. We are asked to include quantitative data to supplement quotes or video/audio clips. Qualitative-based user researchers, including myself, may look towards surveys to help add that quantitate spice. However, there is much more to quantitative data than mere surveys and, often times, surveys are not the most ideal methodology.

If you are so lucky as to be churning out user research insights that your team is using to iterate and improve your product, you may be asked this (seemingly) simple question: how do you know your insights and recommendations are actually improving the user experience of your product? The first time I was asked that question, I was tongue-tied. “Well, if we are doing what the user is telling us then, of course, it is improving.” Let me tell you, that didn’t cut it.

Quickly thereafter, I learned about benchmark studies. These studies allow you to test how a website or app is progressing over time, and where it falls compared to competitors, an earlier version or industry benchmarks. Benchmarking will allow you to concretely answer that above question.

How do I conduct a benchmarking study?

1. Set up a plan

You have to start with a conversation with your team, in order to agree on the goals and objectives of your benchmarking study. Ideally, you answer the following questions:

- First and foremost, can we conduct benchmarking studies on a regular basis? How often are new iterations or versions being released? How many competitors do we want to benchmark against and how often? Do we have the budget to run these tests on an ongoing basis?

- What are we trying to learn? How the product is progressing over time? How does it compare to different competitors? Understanding more about a particular flow? This will help you determine if benchmarking is really the right methodology for your goals

- What are we actually trying to measure? What parts of the app/website are we looking to measure — particular features or the overall experience? How difficult or easy it is to complete the most important tasks on the website/app?

2. Write an interview script

Once you have your goals and objectives set out, you need to write the script for the interviews. This script will be similar to how you write usability testing scripts, questions need to be focused on the most important and basic tasks on your website/app. There needs to be an action and final goal. For example:

- For Amazon, “Find a product you’d like to buy.”

- For Wunderlist, “Create a new to-do.”

- For World of Warcraft, “Sign up for a free trial.”

As you can notice, these tasks are extremely straightforward. Don’t give any hints or indications on how to actually complete the task. That will completely skew the data. I know it can be hard to watch participants struggle with your product, but that is part of the benchmarking and insights you can bring back. For example:

- “Click the plus icon to create a new to-do.” = Bad wording

- “Create a new to-do” = Good wording

If you would like to include additional questions in the script, you can use follow-up questions, asking them to rate the difficulty of the task

After you complete the script, and once everyone has been able to input any suggestions or ideas, try to keep it as consistent as possible. It is really difficult to compare data if the interview script changes.

3. Pick your participants

As you are writing and finalizing your script, it is a good idea to begin choosing and recruiting the target participants. Although normal user research studies, such as qualitative interviews or usability testing generally call for fewer participants, it is important to realize we are working with hard numbers and quantitative data. It is a really good idea to set the total number of users to 25 or more. At 25+ users, you can more easily reach a statistical significance and draw more valid conclusions from your data.

Since you will be conducting studies on a regular basis, you don’t have to worry about going to the same group of users over and over again. It would be beneficial to include some previous participants in new studies, but it is fine to supplement that with new participants. The only important note is to be consistent with the types of people you are testing with —did you test with specific users of your product who hold a certain role? Or did you do some guerilla testing with students? Make sure you are testing with those users for the next round.

How often should I be running benchmarking studies?

In order to determine how often you should/can run the benchmarking studies, you have to consider:

- What stage is your product at? If you are early in the process and continuously releasing updates/improvements, you will need to run more benchmarking studies. If your product is, further along, you could set the benchmarking to quarterly

- What is your budget? If you are testing with around 25 users each time, how many times can you realistically test with your budget?

- If you are releasing updates on a more random basis, you could come up with ad-hoc benchmarking studies that correlate to releases — this just might not be the most effective way to show data.

You really want to see progress over time and how your research insights are potentially improving the user experience. Determine with your team and executives the most impactful way to document these patterns and trends. Just make sure you can run more than one study, or the results will be wasted!

What metrics should I be using?

There are many metrics to look at when conducting a benchmark study. As I mentioned, many benchmarking studies will consist of task-like questions, so it is very important to quantify these tasks. Below are some effective and common ways to quantify tasks:

Task Metrics

- Task Success: This simple metric tells you if a user was able to complete a given task (0=Fail, 1=Pass). You can get more fancy with this once, and assign more numbers that denote the difficulty users had with the task, but you need to determine the levels with your team prior to the study

- Time on Task: This metric measures how long it takes participants to complete or fail a given task. This metric can give you a few different options to report on, where you can give the data on average task completion time, average task failure time or overall average task time (of both completed and failed tasks)

- Number of errors: This task gives you the number of errors a user committed while trying to complete a task. This can allow you to also gain insight into common errors users run into while trying to complete the task. If any of your users seem to want to complete a task in a different way, a common trend of errors may occur

- Single Ease Question: (SEQ): The SEQ is one question (on a 7-point scale) that measures the participant’s perceived ease of a task. It is asked after every task is completed (or failed)

- Subjective Mental Effort Question (SMEQ): The SMEQ allows the user’s to rate how mentally difficult a task was to complete

- SUM: This measurement allows you to take completion rates, ease, and time on task and combine it into a single metric to describe the usability and experience of a task

- Confidence: Confidence is a 7-point scale that asks users to rate how confident they were that they completed the task successfully.

Using a combination of these metrics can help you highlight high priority problem areas. For example, if participants respond with a high confidence they successfully completed a task, yet the majority are failing, there is a huge discrepancy in how participants are using the product, which can lead to problems.

Questionnaire Metrics

- SUS: The SUS has become an industry standard and measures perceived usability of a user experience. Because of its popularity, you can reference published statistics (for example, the average SUS score is 68).

- SUPRQ: This questionnaire is ideal for benchmarking a product’s user experience. It allows participants to rate the overall quality of a product’s user experience, based on four factors: usability, trust & credibility, appearance, loyalty

- SUPR-Qm: This questionnaire for the mobile app user experience is administered dynamically using an adaptive algorithm.

- NPS: The Net Promoter Score is an index ranging from -100 to 100 that measures the willingness of customers to recommend a company’s products or services to others. It is used to gauge the customer’s overall satisfaction with a company’s product or service and the customer’s loyalty to the brand. The NPS can be applied to both consumer-to-business and business-to-business experiences.

- Satisfaction: You can ask participants to rate their level of satisfaction with the performance of your product or even your brand, in general. You can also ask about more specific parts of your product to get a more fixed level of satisfaction

What do I compare my product to?

After you have completed your benchmarking study, what should you be comparing those numbers to and what should I aim for in order to improve the product? There are general benchmarks companies should aim for, or should try to exceed. Below are examples from MeasuringU:

- Single Ease Question average: ~5.1

- Completion rate average: 78%

- SUS average: 68

- SUPR-Q average: 50%

You can also find averages for your specific industry, either online or through your own benchmarking analysis. For example, this website could show you how your NPS compares to other similar companies.

Finally, you can compare yourself to a competitor and strive to meet or exceed on the key metrics mentioned above. Some companies have their metrics online, so you can access their scores. If not, you will have to conduct your own benchmarking study on the competitors you are looking to compare your product to. When comparing against a competitor, always remember you don’t really know their customer’s satisfaction with their product, so make sure to keep that in mind when drawing conclusions!

Even if you have to start small, benchmarking can grant you a world of insights into a product, and can be a great tool in measuring the success of your user research practice at a company!

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]

Interviewing as a User Researcher

To start, we, as user researchers, are a weird niche. We don’t really have too many tangible deliverables we can show people, at least ones we exclusively worked on, we can’t always share insights we’ve gathered at previous companies, our user interview sessions are often confidential and anonymous so we can’t share those and, most times, showing someone a discussion guide example doesn’t give them an actual idea of how you perform interviews.

I’ve discussed how to create a UX Research portfolio through storytelling, but how can you translate your skills to a live interview? What is important to show or talk about during interviews, as a user researcher?

Thinking back to the (many, many) interviews I have taken part in, I have compiled a list of important topics to bring up or give examples of. Of course, this is merely my experience being generalized across numerous variables and situations. However, if you are preparing for your first, or fiftieth, interview, reviewing these ideas may help during the interviewing.

What to bring up in a UX research interview:

- Start by showing enthusiasm and try to maintain that throughout your entire interview. There is a common idea that researchers should be excited about problem-solving, conversations and challenges. We should bring a spark to a company that helps others get excited about research. If you are enthusiastic about your job, and are personable during your interview, most companies can use this to judge how you may act in a day-to-day environment

- It is very important to highlight how you have incorporated teamwork into and collaboration in you user research practice. Who have you worked with before? Was it just the product team or did you work across different departments? What was it like to work with others? What were the challenges you have faced? Some of the joys? This is a time I like to reference specific moments in my career. I usually will also bring up how I have managed to get buy-in from team members, as that tends to bring that question naturally into the conversation

- Similar to teamwork and collaboration, it is important to bring up your skills in communication. This can include many different examples, such as sharing research insights to teams and executives, conveying the value of user research across an organization, or speaking up when you see a need for research

- I often say and believe I should treat colleagues similarly to how I treat users because, in a way, my colleagues are users of my research. With that, I have to understand what they need and want from me, what they are expecting and any barriers or fears they are facing. I talk through an example of when a team came to me with a very confusing project idea. Instead of getting pigeon-holed into their initial questions, we were able to take the time to discuss what they were really looking for and expecting. I empathize with my colleagues as much as I do users. I don’t expect internal stakeholders to be perfectly articulate when describing what they want from user research

- Most companies will want to know how I approach problem-solving, of course, since that is a huge chunk of my day-to-day job. This point may be similar to the one just above it — in order to approach a problem, you have to understand where that problem is coming from and have full context. This means, not jumping directly to a solution but, instead, taking the time to speak with everyone involved in order for you to have a proper and deep understanding of the problem in front of you. Even if you are 95% sure you comprehend what someone is requesting from you, there is little harm in double-checking. You can chat about timelines here, as well, how understanding the problem can ensure reliable and useful results are delivered as quickly as possible

- Give your interviewer(s) concrete examples that reference the past. If they ask you a question, instead of speaking to the skill you have, reference a previous project or moment that highlights the skills they are asking about. By doing this, interviewers are more likely to think of you as a human, just like themselves, and they are better able to relate to what you are saying (maybe it will trigger a memory for them, which could jump start a conversation)

- I will briefly sprinkle in tools I am familiar with, as I’m brining up examples. This gives an extra boost of credibility, especially if you talk through a challenge you faced (such as remote synthesis sessions with team members) and how you took the time to find a tool to help (mural)

- If they don’t outright ask you, I try to reference why I am excited about the specific company and opportunity. For example, I tend to talk about how the opportunity could be a great challenge for me, get me to the next level and provide a solid learning experience. Although I do reference how the company or job is different or unique, I do also talk about how there are similar components to what I have done in the past, so I will be able to effectively meet the job requirements

- Please, please, please ask your interviewers questions, it can be anything, really, but, especially as a user researcher you must ask questions. It can be about the role, the company, the culture, what they like/would improve about the company, it could be about their dog, just ask some questions. Be the curious researcher I know you are, even in the interview process

Take deep breaths and make your interview more of a conversation. Also, remember, you are interviewing them as well. If something doesn’t feel right, don’t always blame yourself.

Exercises/tasks during the interview process

I have seen a few types of exercises or tasks given during user research interviews, but they are generally all relatively similar: “if X team came to you with X problem they wanted to solve or question they wanted to answer, how would you respond? What would your approach be?”

This can be very overwhelming, especially when you are trying to think of your entire process, from end-to-end, in thirty minutes, and then considering about you will be presenting said thought process to a group of people who already know the answer they want to hear.

I believe the biggest reason for these tasks is to understand your thought process. With that in mind, try not to jump right into a solution. Often, I find, there is not as much information as I would like to begin forming a research plan. I always start by brainstorming questions I would have based on the prompt. I often ask if there is prior research done on this topic and note that I would like to have further meetings with the team to really understand their desired outcome of the research. Thereafter, I jump into forming a research plan based on the given information.

I create a research plan because I feel like it includes an overview of how I think about problem-solving and my overarching approach. I am usually able to fit in everything, as well, and I typically dive into more detail as I am presenting. For example, I like to include topics such as objectives/goals, anticipated timeline, target audience (touch upon recruiting, if possible), both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, discussion guide (sample questions or sample tasks), which stakeholders I would include, expected outcome (and expected challenges, if I have time), synthesis and how I would present the insights once the research is done. Once I have this skeleton filled in, it makes it much easier for interviewers to understand my overall approach, and we can dive into the detail behind each section when I present.

An additional note: send a thank you email.

Again, this has just been my experience when interviewing for user research roles and I’m sure I’ve missed some information (as we sometimes do during interviews), but I’m hoping it can serve as a guide to prepare you and make the process less stressful! Happy interviewing!

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]

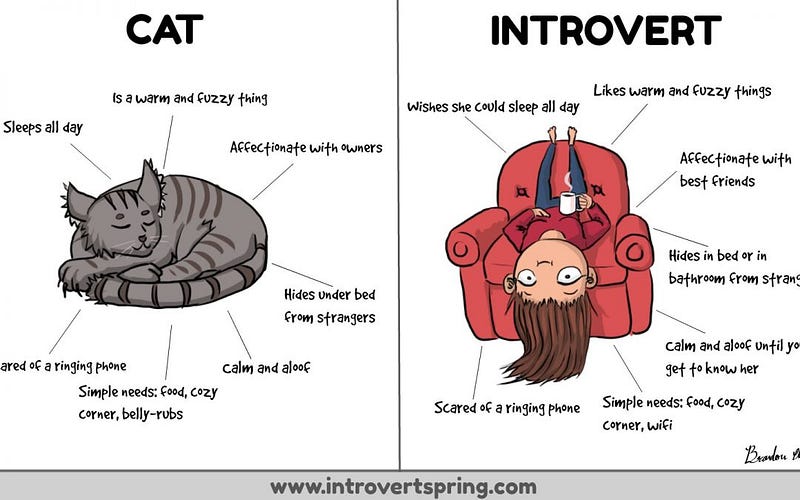

An Introverted User Researcher’s Guide to Solo Networking in Tech/Product

Let me start off by saying two things:

1. I am truly an introvert. If you put me smack in the middle of a party, my face will turn the color of a sunburnt lobster and I will stutter and stammer until I make my way to the corner, the bathroom or the door. I prefer to Irish exit instead of saying goodbye, despite how much I love you. Before I moved to Berlin, I shirked at the idea of a goodbye party or anything putting me in the center of attention

2. I have read hundreds of articles and books on extroversion and networking. I listened to podcasts, attended events on networking (meta), gathered advice from mentors, but nothing pushed me. It took years for me to get to this moment and, looking back, I surely would’ve laughed in your face if you told me I’d be writing this article (well, probably not in your face since I’m self-conscious, and all)

*From here, scroll down about 3–4 “scrolls” to get to bypass my story and arrive at the actual how-to*

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s move forward on the subject matter. When I tell people I’m close with that I’m shy or introverted, they laugh. I always get the “no you’re not!” coupled with a chuckle and slap on the back. What they don’t recall (nor could they) was the internal turmoil I felt when meeting or interacting with strangers. The lightheadedness, the shaky, sweaty hands (thank goodness handshaking is relatively out of style), the mantra of “don’t turn red, don’t turn red,” and the sticky, dry mouth that catches your tongue, making it impossible to form already jumbled thoughts into coherent sentences. Socializing is a dream.

So, here I was. I had just started a new career in user experience research, after being in the field of academia and psychology for nearly my entire life (which doesn’t require too much socializing). User research, however, was a complete 180 requiring constant interviews with strangers, workshop facilitation, teaching, negotiating, convincing others to buy into my ideas. By some grace of, what I believe was karmic retribution, I was given a manager and mentor who helped me develop these skills. He taught me almost everything I know about user research and helped build the foundation with me. (Shoutout to John Labriola!)

Anyways, I distinctly remember a moment (which ties back to the point of this article, I promise) when we were sitting in one of our weekly 1x1 meetings (yes, he was that awesome) and I asked him, “how can I learn more and move to the next level?” Since he knew me so well, his first recommendation was a list of books. Ca Ching! I loved reading. Check. Easy peasy. I was about to proudly broach the next subject on my list when I heard him continue on. “The other thing is going to meet-ups and networking — I can’t teach you everything and it’s very important to learn what others are thinking.”

I swear, the sweat started to pour halfway through his sentence. I still remember the thumping of my heart against my chest at the thought of walking into a room of complete strangers, and the way my tongue instantly felt like a foreign intruder. My teeth grated, my jaw clenched and I nodded. Why couldn’t I just read? Or maybe watch YouTube videos? I was that person who loved video games they could play and win on their own — Pokémon, hell yeah I caught all 151 (Mew was real and I refuse to acknowledge the 10,000 additional Pokémon that have come into existence since the originals). I caught them all by myself and, yes, that means I bought a whole other Gameboy for myself, both red and blue versions and I sure as hell connected them and traded by myself. Yeah, I didn’t outgrow that.

I ignored my manager’s advice for some time, much preferring quiet nights on my couch with my user research books (or, let’s be real, Netflix). Then one day, I got laid off. There was a massive downsize at the company I was working for and about half of the employees were cut. I no longer had my constant stream of advice, my stability, my manager, my mentor (well I did, but he wasn’t getting paid to manage or mentor me anymore)…nor did I have a paycheck. It was time to hustle and get a new job, but, consequently, it was also time for Thanksgiving and Christmas, when companies are generally not feeling the hiring vibes.

What was I to do in the meantime, while I was submitting application after application, getting confused about what cover letter went best with which mission statement? I didn’t want to go stale and forget all my user research methodologies. I needed more than the occasional lunch/coffee or messaging my manager in panic mode. I didn’t want to fall behind. Then, one day, it hit me, I had to network. I no longer had a choice. I had to go out into the world of people who did tech and product things and have awkward conversations that hopefully turned into good ones.

I was led to this very moment by a force greater than me. And, up until this moment, I have gone to countless meet-ups, created an entire network of people I rely on in the UX and product world, facilitated and founded meet-ups, spoken at meet-ups (in front of an audience, yes), reached out to complete strangers for advice, created and marketed my own freelance brand, got shot down by countless clients and job opportunities, cried, walked up and introduced myself to strangers at conferences, laughed, felt like a complete failure and felt like I was on top of the UX research world. And now, I am redoing all of that in Berlin. Hint: the more you do it, the easier it gets.

How did I go from the moment in my Brooklyn living room, contemplating what was next and how I was going to pay next month’s exuberant rent check to the person writing this article?

I forced it. I faked it. I gave myself no other choice. I wished there was some magical formula that made me the most compelling, storytelling, captivating extroverted person out there, but I knew wishing would get me nowhere. I took an audit of the things I felt I was good at and enjoyed: listening, asking questions, writing and humor (most times self-deprecating). I thought about how to apply these to the cringingly awkward conversations (or lapses of silence) I had nightmares about.

I prepared for my first meet-up like an astronaut preparing for her first time in space, or how I might imagine she would, with a whole lot of work. I made lists of topics I could bring up (outside of the weather or traffic), articles or books I had read recently, questions I wanted to ask people (ones I had previously asked my manager, so I knew they were pretty good quality), researched the company the meet-up would be held at and, finally, charged my phone battery in case people avoided me like the plague and I would be scrolling through Instagram for hours, with a pensive look on my face, pretending I was reading thought-provoking Medium articles. I memorized my lists, pulled up Google Maps, took many a deep breath and was off to my first solo meet-up.

How I have learned to network as an introvert

For me, there are a few different stages in the introverted networking phase, some of which I now skip over, but they helped me build up the confidence to where I am now.

Pre-event

- While it is helpful to write lists of questions or topics you would like to discuss, for when your anxious brain exits the building without you, it is equally as paramount to come up with answers to your own questions. For a while, I talked them through with myself or wrote them down to practice, in case someone turned around and said, “what do you think of that?” This helped build my confidence to have casual conversations and to give my opinion

- Write and memorize a small pitch about yourself. Similarly to job interviews, people want to know what you do and what got you into the field. Something I quickly learned is that people don’t want your life history, they would like a succinct version. Mine goes along these lines:

While I was getting my MA in Psychology, I worked in a mental hospital for about two years. I loved being able to talk to and help people, but the burn out was real! I wanted to take my love of listening, understanding and helping into a different field, and that is when I found the wonderful niche of user experience research! I’ve been at start-ups and larger companies, both full-time and as a freelancer. I love how this field continues to change on an almost daily basis, and how able we are to impact it!

This takes about a minute or so to say and gives people an understanding of who I am, where I came from and a brief blurb of why I love being a UX researcher. This statement isn’t invariable, but I always keep it short so people can ask me questions, if they wish. Try your own! And, most importantly, talk yourself UP, not like you are the absolutely best and most untouchable UX’er in the world, but don’t be scared of your own accomplishments or opinions - Read some articles or tweets about what is happening in the UX world, research the company hosting the event (they often have job opportunities) and stalk the speakers on LinkedIn (gentle stalking is allowed). This will give you a bit of confidence when walking up to strangers, especially if they work at said company or are a speaker

- Don’t forget your business cards, as I always do

- Optionally, and if you want to really challenge yourself, create some goals. I want to talk to 5 new people, receive 3 emails from strangers, ask a speaker a question, approach someone who works at the company for a job opportunity, or just simply sit through the entire meet-up with a smile on my face

During the event

- Take that deep breath before entering the building and know that you are just as qualified, smart, interesting as anyone else in there

- Recognize there are people there who are just as nervous, if not more nervous, than you are (I mean some people are getting up to speak in front of an audience). You can often spot the shy ones as people scrolling on their phone, while frequently looking up to check out if anyone near them is approachable

- If you want to go up to someone, you can do this one of two ways: choose a group of people (more than two) who are having a conversation or approach someone who is alone. When I first started, I would spot a group, usually near the food table, and I would make my way over to the food, loitering around them until I sidestepped my way into the conversation. How did I sidestep? I walked closer to the group, made eye contact with a one or more people in said group, which eventually turned into a silent invitation to join. As I became more brave, I would say something as an opening, but just joining via nonverbal communication works too. If I went for someone who was alone, it was, again, usually near food or drink, I would smile at them and start with, “hey, I’m Nikki” and an extended (sweaty) hand. I followed-up with, “how did you hear about this event?” That usually gives enough information for follow-up questions. Whenever I did this, my anxiety was through the roof, but once you make eye contact and smile, there’s really no going back (well, there is, but it is a bit weird). Most people standing alone also want to be engaging in conversation, unless they are absorbed in their phone, so you might be saving a fellow introvert!

- If walking up to strangers is still too much, you can also stand alone, WITHOUT YOUR PHONE OUT, and look around the room with a smile on your face. No crossed arms either. This body language usually indicates you are open for conversation

- It is usually easy to spot the facilitators of the meet-up, so start a conversation with them saying how excited you are for this talk and thanking them for putting this together. They will sometimes introduce you to other people in charge, speakers or the host of the meet-up

- If all else fails, get some food, sit down and just promise yourself to make it through the meet-up. You can plan everything in advance and still not feel comfortable or confident enough to network, but you are there and that is really all that matters

At my first solo meet-up, I could feel my insides shaking, and my body temperature oscillating between hot and cold. I stood paralyzed with a (probably crazy) smile plastered to my face, completely alone. My mouth was so dry I could barely swallow, I don’t even think I could’ve eaten the food I picked up. I tried to make eye contact, but it was fleeting. It felt like I wanted someone to acknowledge me, but I also wanted zero attention. I eventually sat down alone, listened to the talk and abruptly left. I felt defeated when I returned home, no new contacts or introductions or job opportunities, even after planning so well. I wanted to cry, and probably did, but after a while I realized I had done something. Despite my overwhelming fear, I had chosen to leave my apartment to go sit in a room with strangers, totally alone. That, in itself, was the accomplishment of the night. If I could choose to do that, next time I could choose to introduce myself to someone. And that I did.

After the event

- Follow-up with anyone that you meant within 24 hours, whether this is an email saying how interesting it was to speak to them or setting up a coffee meeting, just reach out

- CONGRATULATE YOURSELF — even if you spoke to no one and scrolled through more of Instagram or Facebook than you thought possible, you still accomplished what you had previously felt was impossible. You did not fail, you took a step forward

- Take what you learned from this event and apply it to the next. I learned that I had all the lists, but no introduction. That is when I came up with my genius opening of “hi, I’m Nikki.” I also sat down with myself and rally figured out why I was so scared. I didn’t want to come off as a bumbling idiot. My mantra became “you are not a bumbling idiot” as I was walking up to introduce myself to someone. Since my brain was so busy mantra-ing, it had less time to tell me how nervous I was. I just had to be sure “hi, I’m Nikki” came out instead of “hi, I’m not a bumbling Nikki idiot”

- Be patient and kind to yourself. I think I went to two meet-ups without speaking to anyone. At the third, someone approached me while I was standing alone, mantra-ing and smiling. Take however long you need to work up to this

- Next time, take a friend or colleague. I know this article is meant to be about solo networking, but sometimes you need an extra boost. There’s no harm in brining someone along, but just make sure you two don’t spend the entire time talking amongst yourselves

So, what is the answer, really?

Recently, I have had an embarrassing epiphany. Life takes a lot of work. This is not to say I haven’t put in any work, but I have realized, if I want to really go after something and succeed, especially if it doesn’t come naturally, I need to put in the time. I can’t cut corners, and there is no magical pill or article that will make you perfect. I have known this for a long time, but, I think part of me has always just wished there was: a pill for weight loss, for making me a better storyteller or creating a more captivating personality, for improving my writing or even getting me to write, for curing all my insecurities. Or, I wished I could read about someone else’s journey and, poof, epiphany, my life would be changed for the better!

And that is what frustrates me as I write this. I’m sure, in my quest to become a more extroverted introvert, I have read articles similar to the one I am writing right now, with similar experiences or advice, and I thought “this isn’t helpful. The person is just telling me their path led them to this moment or they ‘just did it’ and it worked.” Unfortunately though, that is the thing. We’re all human, we all boil down to the same thing. We all have to have our own moments of clarity, realizations, failures, success. Yes, an article, movie or talk can inspire us, but we need to actually do the thing. And, maybe that is why I am here writing this. I’m here to tell you:

You can do the thing. You are more than capable, right now, in ten minutes from now, a month from now, even yesterday! Do whatever you need to do, whether it’s making lists or talking yourself up in the mirror, then leave your apartment and go to the event (or whatever else you may want to do). Take your step forward, whether it be a leap or a baby step.

Better UX Research Through Body Language

Your body language is just as important as the questions you ask

Body language is a very important concept in our everyday lives. It affects work meetings, romantic relationships, friendships, and how we engage with complete strangers. For something so present, and very natural for us, it is also extremely unconscious. We show our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions through body language all the time, but we are often unaware of how people perceive our body language. The impact can be huge, from settling down a confrontational meeting, to inflating your sense of confidence, to degrading a complete stranger.

Body language is a very important concept in our everyday lives. It affects work meetings, romantic relationships, friendships, and how we engage with complete strangers. For something so present, and very natural for us, it is also extremely unconscious. We show our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions through body language all the time, but we are often unaware of how people perceive our body language. The impact can be huge, from settling down a confrontational meeting, to inflating your sense of confidence, to degrading a complete stranger.

When you conduct in-person user research, there are a lot of moving pieces to juggle: You are meeting a (potential) complete stranger in an environment that is new to you and/or to the participant, and the interview is likely taking place in a work setting, which can feel uninviting. A host of factors play into how a participant responds within this setting.

A huge part of user research is making the participant feel as comfortable as possible in the above scenario, so they are able to share honest feedback as candidly and openly as possible. This feedback may not necessarily be easy to share, whether it includes personal stories or they are giving negative feedback that puts themselves in a negative light. The key question is, how quickly can you get to this relationship? If you only have 60 minutes (or less) with a participant, it is essential to make them feel as comfortable as possible, as quickly as possible.

How can researchers change their body language?

There are a handful of common nonverbal communication techniques you can employ in order to make yourself, as a researcher, look more friendly, engaged, and interested, and in turn make your participants feel more comfortable with you. (Bonus: This also works with colleagues, partners, and friends!) Pro tip: It can be easy to forget these “common sense” techniques in the process of research, so I keep a small checklist I look over before the participant enters.

- Make sure you are sitting at the same level as the participant. This means your chairs are at the same level, you are eye-to-eye, and you are never standing over someone. When possible, sit next to the participant, as opposed to across from them, since it will feel more like you are peers and less like an interrogation.

- Try to take up as little physical space as possible, as you want the participant to feel like the most important person in the room. This means putting your legs together and physically making yourself feel smaller. Leaning forward helps with this, as you are less likely to be splayed about and will appear more compact.

- Try to dress similarly or in a relatable way to the interviewee. This isn’t always possible, as you can’t predict what participants might wear, but do your best. At times, this has meant walking into a more formal office with casual attire on, since I knew the participants would be more likely to show up in jeans and a T-shirt rather than a suit.

- When speaking to a participant, make sure you are slightly leaning forward. With this position, you are less likely to cross your arms, which can be a sign of withdrawal and disinterest. Instead, by leaning forward, you are showing the participant you are intrigued by what they have to say and your attention is focused on them.

- It is important to nod a lot, or show micro-expressions that indicate you are not only listening, but also understanding what the participant is saying to you. I will occasionally sprinkle their monologues with “mmhmm” or “okay” or “oh yeah.” People get uncomfortable when they go a while speaking without any confirmation that the other side is still with them. This is especially important on a remote phone or video call.

- Always make sure the participant knows what the research session will be like. This includes explaining the setup, how long the session will be, what they can expect (I always say it will be a conversation on X topic), and what you want out of it. This way they aren’t walking completely blindly into a situation and can mentally prepare themselves for the upcoming session.

- Be careful of too much eye contact — it is important to make the participant feel like you are paying attention by maintaining a gaze, but that doesn’t mean intently staring into their eyes. Who wants to be stared at?

- Pay attention to the tone of your voice. Often, a researcher can sound aggressive or intense when asking questions, without intending to be. I try to speak in a higher and softer pitch to make the questions sound more conversational, and less like an interrogation.

- Please please please, always put phones, computers, watches, Kindles (I’ve seen it happen), and any other electronic device away. One surefire way to make a participant feel uncomfortable and unheard is the constant pinging or checking of notifications. This means everyone in the room besides the notetaker — and make sure you deliberately share that there will be a notetaker who is taking down only confidential notes.

More advanced techniques and frameworks

The ideas stated above are fairly well known, so I wanted to share some more advanced ideas I have formulated or heard of over the years. These concepts are a bit more thought provoking and take more effort to utilize.

Where is the research taking place?

Are you bringing the participant into your environment, or are you entering the participant’s environment? This will dictate who the host is and who the guest is, which will help determine how to behave in either setting. If you are hosting the participant in your space, whether that be an office or a research lab, it is your job to welcome them into your space as if they were a guest at a dinner party. They probably aren’t sure where to go or what to expect, so common direction and explanations, such as where the bathroom is located, asking them if they want any water, and making sure you collect them from the lobby on time, will make them feel more comfortable in a foreign environment.

On the flip side, as a guest in a participant’s environment, you can take a more flexible approach. There might be phones ringing during the research session, they may be running late, or people may walk into the office space by mistake, so keeping an open mind with a lot of smiling and appreciative statements is key. Also, always say yes to water if someone offers; it makes them feel more helpful!

Get into character

I have my user researcher character I take on, similar to an actress in a play. My user research character is very positive and optimistic, constantly smiling and thanking people. When in character, you let go of your day-to-day stress and problems and the fact that you spilled coffee all over yourself while walking your dog early that morning. Instead, you take a deep breath, put on your user research mask, and adopt the researcher attitude of being curious, interested, and invested in your participant.

Make the participant feel more important

This has to do with status and the hierarchy of the relationship. Generally, you do want to lower your status in a research interview, and you can do this by lowering your chair slightly, taking up less space, and boosting the participant’s status with statements like “I’m super excited to talk to you; we couldn’t do this without you.”

There are, occasionally, certain situations that may require you to heighten your status. If I am speaking with a scientist about a complex product or concept, let’s say, I might level-up my status, so I seem smarter and worth talking to, like I can understand them. I could do this by taking up more space or speaking more loudly. Keep status in mind, especially when you sense the participant is uncomfortable.

Downplay the prototype

A great way to get honest and open feedback is to downplay and lower the status of the prototype being tested, so the participant feels as though they can discuss and criticize what is in front of them. If they feel like the design or experience is not set in stone, they are more likely to give constructive feedback. If the prototype is presented as a finished product, people will be less likely to give their opinions on how to improve it.

Always be aware of how the participant is feeling

If something isn’t working, be flexible and try to troubleshoot the situation. Maybe you are lowering your status too much, which is actually making the participant uncomfortable. Be willing to adjust as you go to make the research session even better.

One last tip for participant comfort

Body language aside, the biggest mistake I have seen that makes the participant uncomfortable is poor room setup. Always ensure the room is as minimal as possible, meaning there isn’t a lot of visible stuff in the room. If you are recording, make sure the camera isn’t directly in the participant’s face or looming over them. When colleagues want to participate in watching the research, I make sure to have them dial in, as opposed to having many people in the room, and I always keep the list of people dialing into the video conference hidden — there is no point in the participant knowing there are 15 people watching their every move.

How do you figure out what you are or aren’t doing well? Watch yourself in interviews. You might hate it, but this will help you realize what you’re missing and how to improve these techniques. Another great way is to coach junior or non-researchers. The more you teach something, the easier it is to do it yourself! Watch and learn.

How do you figure out what you are or aren’t doing well? Watch yourself in interviews. You might hate it, but this will help you realize what you’re missing and how to improve these techniques. Another great way is to coach junior or non-researchers. The more you teach something, the easier it is to do it yourself! Watch and learn.

How might we be wrong?

Why User Research isn’t a magical unicorn.

As user researchers, we spend a lot of time and effort on convincing people of the value we could bring. Because of this, we are sometimes hesitant to consider how our results may not hold the best and truest insights. It isn’t necessarily stemming from an egotistical wish to always be right, but more fear-based. We don’t want to lose the buy-in we fought so hard for. If our results are pristine, actionable, innovative, “right,” then we could potentially lose what we worked so hard for: the right to do research.

As I tell many clients and students, user research isn’t the answer. It isn’t a magical unicorn that farts perfect, rainbow-colored insights. User research gives us an understanding of our users so we can make informed decisions. I didn’t say the right decision, but informed decisions. It gives us a direction (or several) that is based off of our knowledge of our users. However, as many times as we say this, user research can often be looked at as the one thing to solve them all (any LOTR fans out there?). When research fails to live up to this impossible standard, stakeholders can get frustrated and shut it down.

We need to ease up on our expectations of research, and use it as guidance as opposed to the one and only true path. With this, user researchers can analyze their results without fear and find where the research may be less valid.

The Concept of Validity

Validity is how well a test or research measures what it was intended to measure. It also the extent to which the results can be generalized to a wider population.

Validity has always been controversial in qualitative research, and many user researchers have abandoned this concept completely, as it sits too much in the world of quantitative data and statistical analysis. As qualitative user researchers, we simply don’t have the large numbers to back up a concept like validity in the same way quantitative data does.

However, validity is important in understanding how you might be wrong about a result. This concept is called a validity threat. They are other possible explanations or interpretations, something Huck and Sandler called “rival hypotheses.” What validity threats boil down to are alternative ways of understanding your data.

How does this occur? It can be for many reasons (have to love confounding variables), such as your participants not presenting their actual views (social desirability bias), missing data points that support/disprove your hypothesis, asking leading questions, or simply having certain biases towards the people or ideas you are researching.

In short, a lot can go wrong, which is why, I believe, it is important to rethink the meaning of validity in terms of qualitative research, instead of ignoring it completely. What do we need to look into in order to redefine validity in terms of qualitative user research?

Two Most Common Threats: Researcher Bias & Participant Reactivity

As humans, we are inherently biased in a given situation. Even if you do everything in your power to remove these biases, they will continue to linger on an unconscious level. This can impact user research when conclusions/results are based on data that fit the researcher’s existing theories, goals or perceptions and the selection of insights that “stand out” to a researcher. These insights or quotes may catch a researcher’s eye, but it is understanding why those pieces of data are particularly important. In order to know this, you have to be aware of your biases and how you will deal with them. Is it by writing them down before you analyze your data or by having a few researchers look through the results in order to see how different people are approaching the insights?

Similarly to bias, the user research will always have an influence on the participant, causing a degree of reactivity from the user. Quite obviously, eliminating the impact a researcher may have on a participant is impossible, so the goal is not to eliminate, but to understand what the potential impact may have been and use it when analyzing results. There are some measures a researcher can take to decrease a participant’s level of reactivity, such as not asking leading questions, dressing similarly to the interviewee, sitting on the same level and using open body language. Like with bias, it is important to understand how you could be influencing the participant and how that may affect the results.

Write a Memo

In order to help ourselves better understand what threats we face, we can do a simple exercise that involves writing down the answers to the following questions:

- What do you think are the most serious threats for this research objective? Why are these the most serious threats? What are the main ways you might interpret the data incorrectly? Be confused about the insights? How could you interpret results incorrectly?

- What do you think are the most serious threats other people (colleagues, stakeholders) may have? Why do you feel this way?

- How do you think you can best assess and mitigate these different threats, for yourself and others? How might others be able to help you assess and mitigate the threats?

What Else Can Help?

There are several other ways qualitative researchers can explore and impact validity:

- Long-term studies: By continuously interviewing and observing participants, you are able to learn more about them, beyond what they tell you in a 60-minute window. You can understand users much more deeply, and start to grasp which insights or quotes may be shallow or random. This goes against many company’s desire to do research quickly, but, if you have the buy-in and time, the more research you do, the more valid and generalizable your conclusions will be

- Rich data: It is wonderful when someone can take notes for you during an interview, or when you can take notes yourself, however, people tend to drift in and out of focus during interviews, so it is difficult to pick out everything a participant says. Note-taking can be an early form of bias — someone writes down what they deem as important — a better alternative is to get a transcript, record the interview and have several people taking notes to compare later

- Respondent validation: Humans do a great job of assuming…as in we do it a lot, but we aren’t actually very good at it. If a participant explained something to you, and you were a little lost or confused, don’t just assume you will figure it out later. Always ask participants to clarify, when it makes sense to. This is the easiest way of ruling out the possibility of misunderstanding what a participant meant. This can also help you understand your biases and misconceptions

- Don’t ignore data: I know we all want to get it right, especially when we are getting pressure from above, and we want to deliver the most favorable results. With this type of tunnel-vision, we can easily miss or ignore data that goes against the more flattering hypothesis. Even if the data sucks and tells you your company is doing everything wrong, it’s better to report that than waste time. Another note on this, make sure you have a few hypotheses lined up, not just the ones everyone wants you to validate — write these down like your biases — that way you are looking at the data from several different standpoints

- Comparing data: Talk to your users at different times of day, in different settings and in different ways. This helps rule out confounding variables. For example, if you are a health company and speak to all of your users first thing in the morning, you may hear a very different story from them than those same users later at night, when they are tired and would much rather reach for potato chips than your juice cleanse. Ensure you aren’t replicating the exact settings for all your users, and you will get data you can more confidently generalize.

Even with these approaches, there is no way to truly know if your qualitative results are perfectly valid (in fact, they will never be, as is the same with quantitative data). But, this is a step towards a more open-minded approach when thinking about the validity and qualitative research. User research isn’t supposed to be known for sure, as nothing in life is. We need to give researchers a break and let them approach their data with the potential that it isn’t always the right answer. That way, we can work together towards more informed and less forced solutions for our users.

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]

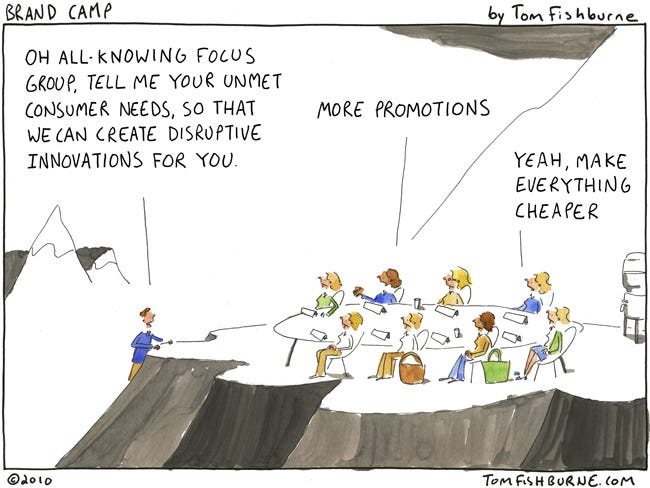

I’ll say it: focus groups suck

Let’s put a bunch of people in a room, they said. It will be fun, they said.

Focus groups are still one of the most highly debated user research methodologies. In my time within this field, I have met people who either hate them or believe them to be effective. There really isn’t an in-between or grey area with focus groups. What are focus groups? A group of people assembled by a company to participate in a discussion about said company or product. Ideally, the company will obtain feedback in order to help determine any changes, improvements or innovations.

As you may have gathered from my title, I find them less than ideal. I have really tried to make them work, but the times I have used them, I have slowly watched them fizzle into a pile of nonsense and waste of everyone’s time. I mean, they seem as though they could be so efficient and full of insights, but try as I might, the cons always seem to outweigh any benefits.

For those of you who are focus group enthusiasts, I promise I am not trying to rain on your group parade. Instead, I am merely pointing out some negative effects of focus groups that could skew data, causing a company to go in the wrong direction and, subsequently, swear off future user research. And, of course, offer a potential solution (because what would a product article be without solutionizing).

Groupthink

Groupthink is a very unconscious and common practice that occurs when people come together to have group discussions. Oftentimes, the participants in the groups will conform to other’s opinions in order to perpetuate harmony, which can potentially override individual’s thoughts or feelings. This ties back into the concept of the social desirability bias, which unconsciously pushes people to answer questions in a way that deems them more favorable to others.

As an example, say you bring up a new feature or an improvement your company wants to explore with the group. If a few people in the group find this feature or improvement favorable, and voice their opinions, there is a high chance the rest of the group will tend to agree, even if they think the feature is useless to them.

The reason we conduct user research is to talk to a wide variety of users who have differing opinions on what they need or what goals they are trying to achieve from a product. Groupthink tends to discourage creativity and individuality, leading to repetitive and, potentially, skewed results. These results could encourage companies to launch a feature that isn’t used by the majority of their user-base.

Solution-focused

As a user researcher, you really want to understand the motivations behind why users want what they say they want. In focus groups, it is very difficult to uncover these underlying thoughts. When people get together for a focus-group, the immediate nature is to come up with a solution, or for participants to say what they want from you, instead of how they would actually use the product or the goals they are trying to achieve with the product.

Being in a group doesn’t facilitate deep, analytical conversation. You can only understand so much about one participant’s perspective before another participant jumps in to elaborate or you have to move on to the next topic.

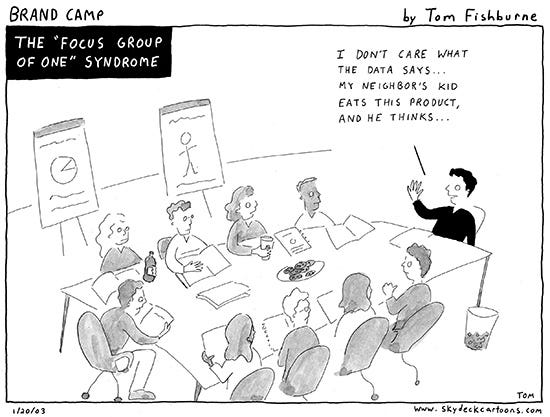

Focus Group of One Syndrome

The focus group of one syndrome doesn’t only happen in focus groups, we see this kind of behavior in meetings and classrooms as well. In the context of a focus group, one person tends to steer the conversation with his/her thoughts, feelings and opinions. This type of domineering personality can be detrimental to a focus group, as it can predominate the entire conversation and leave the results heavily biased by one or two strong opinions. This can negate the the views of the less articulate or more reserved personalities. In the end, what you ended up with is results from one or two people, as opposed to the larger group you were aiming for.

Conflicting Personalities

When you bring together a group of people, for whatever reason, there is always the potential for conflicts to arise between personalities. Maybe you have two strongly opinionated people, whose views are at opposite ends of the spectrum. While this could be valuable information, it could also lead to fights or participants speaking over each other. This opposition can quickly detract from the interview and lead to a fight for power, in which the two conflicting participants overtake the interview with an argument.

Is there a solution? Unfocused groups

The goal of the unfocus group is to get a broader range of opinions and feedback about a product. During this time, the participants are told they will be having an open-ended conversation about a very loose objective, such as the intersection between communication, medical information and technology (or whatever your company is trying to understand). You bring in participants who are on the tails of the normal distribution curve, in order to gather more diverse feedback.

The combination of this more “unusual” group and the ability to have a real, open-ended conversation with little agenda, there is a higher potential for more creativity and true insights to emerge. Although the ideas may be more lofty or may not fit exactly with the company’s vision, you can pull the ideas back a bit to see if they can serve the bigger market.

It isn’t a fool-proof solution, but it offers another alternative to using the traditional focus groups, and may give you actionable, more innovative results.

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]

Why do we make user research so difficult

We’ve lost our focus

The Uphill Battle

The most basic and well-known definition of user research is “understanding user behaviors, needs and motivations through observation techniques, task analysis and other feedback methodologies. It is a process of understanding the impact of design on an audience.” (Usability.gov) In order to truly understand said behaviors, needs and motivations, you need to do research. The reason we want to understand the above is to enable us to make products tailored to our customers, for a more delightful experience (and more money).

Instead of this simple and straight-forward definition, which, I must admit, most things in life are not simple and straight-forward, user research is often seen as a battle, in which the user researcher is attempting to cut down bushes of thrones with a dull sword.

The Requirements List

User research has become less user-centric and, instead, has become a list of requirements or obstacles a UX’er must overcome. Proposing a user research initiative feels less about understanding a user, and the potential and excitement that could come from that, and, instead, feels more like defending territory or running a political campaign.

Now, there seem to be so many barriers before starting research, or even proposing a research project. One must:

- Get stakeholder buy-in by convincing people that, while research is not the magic answer or solution, it is worth the time, money and effort to understand the users

- Defend the small number of users needed against everyone’s belief that statistical significance and change can only come by speaking to over 25 people (despite everyone’s concern with said time, money and effort)

- Show ROI of research and how it aligns with business KPIs — this is an important skill and strategy, but here is a great article with thoughts against always tying ROI to UX

- Somehow finagle your way into a product backlog/roadmap to ensure user research gets prioritized and done, in order for you to show value

- Actually do research

Make research easy again

More often that not, requirements like those stated above, stem from a place of fear. So, when did everyone become so scared of user research?

Why must we jump through hoops in order to do something most of us know will benefit a company? The number of quotes and examples out there showing how vital user research is to company health and success is impressive (it’s certainly over 25, so I can claim statistical significance). User research can help lead to success stories and happier customers.

The premise of user research is simple: talk to your users and all else will follow (an adaptation from Google’s number one value). We really don’t need hoops, obstacles, pages of evidence and convincing proposals. What we need is to go talk to our users. Go talk to the people using your product instead of the people trying to make your product “perfect,” because, without the user’s perspective, the product will never reach the illusive state of perfection. And, yes, of course it is necessary to have a direction, to have research goals, but spend time defining those instead of arguing the need for research in the first place.

Although the phrase is overused, we all need to make research easy again, so we can truly focus on building user-friendly products.

[embed]https://upscri.be/50d69a/[/embed]

The impostor UX’er

The Syndrome is Real