Ten emotion heuristics: how to read a participant’s body language

As user researchers, we take words very seriously and place most of our importance on what our users are saying. While this is, in fact, where our attention should be placed, we should also consider the body language of our users during our research sessions. I’m not talking about “rage-clicking” or clear sighs of frustration (although those are important too), but more of the subtle body language.

A while back, I wrote about how important a user researcher’s body language is during an interview, and now I want to write about the other side: the user’s body language.

Why is this important?

One of the number one principles (at least one of mine) of user research is:

watch what users do versus just listening to what they say

When we focus all of our attention on what people are saying, we can miss what they are actually doing. And, unsurprisingly, what people say and what they do can be quite different.

I have a perfect example of this. I was conducting usability tests on a new flow we were thinking about implementing. One of the main tasks our users had to do was download multiple images at once. We didn’t make this easy and, previously, our users would have to hack downloading them at once. Once we finally had the resources to tackle this project, I was super excited to test our ideas.

We had one idea in particular we thought was a sure winner. I couldn’t wait to test it with users. We showed it at about ten usability tests and, luckily, I had my observation mindset on. Many of the users said they really liked it. They could finally download multiple images at once. HOWEVER, the majority of users, while telling me that they liked it, struggled with understanding the flow and completing the tasks. In fact, three users clicked on many different areas and appeared visibly frustrated, but still said it “wasn’t bad.”

Had I just been listening and using words as data, I would have pushed forward this idea. Instead, I noticed the struggles. During the interview, I was able to dig deeper into the frustrations beyond the surface. This allowed us to better understand where we needed to improve the UX.

It was after that particular test I started looking more into how to observe user’s behavior and body language during research interviews. I wanted more than retrospective or current self-reporting measures. I searched and found a method that relies on real-time observation of behavior and coding of participants’ facial expressions and gestures. Its creators, Eva de Lera and Muriel Garretta-Domingo call their method the “Ten Emotion Heuristics.”

The Ten Emotion Heuristics:

The heuristics are a set of guidelines to help assess what a user is feeling beyond self-reported measures. As mentioned above, there are times where users actions and words do not match up, and you can use the below heuristics as a way to understand what the user is really feeling, beyond the feelings they may be aware of.

- Frowning. If a user is frowning, it can be a sign of a necessity to concentrate, displeasure or of perceived lack of clarity

- Brow Raising. When users raise their brows, it can be a sign of uncertainty, disbelief, surprise, and exasperation. While surprise isn’t always negative, we don’t necessarily want our users to be surprised or uncertain of the experience on our platform

- Gazing Away. When a user gazes away from the screen, they may feel deceived, ashamed, or confused. They could also very possibly be bored with what is on the screen in front of them

- Smiling. A smile is a sign of satisfaction in which the user may have encountered something satisfying or joyful

- Compressing the Lip. Seeing a user compress their lips is a sign of frustration and confusion. I see this a lot when a user intends to do something, but it does not work, causing frustration and anxiety

- Moving the Mouth. If the user is speaking to themselves, trying to understand or complete a task, this indicates them feeling confused or lost in the experience

- Expressing Vocally. Vocal expressions such as sighs, gasps, coughs, as well as the volume of the expression, the tone or quality of the expression may be signs of frustration or deception.

- Hand Touching the Face. If a user is touching their face during the interview, they could be tired, lost, or confused. This can also indicate a high level of concentration and frustration with a task.

- Leaning Back on the Chair. When a user (or anyone, really) leans back in a chair, it is an indication they are having a negative emotion and would like to remove themselves from the situation. This generally shows a fairly high level of frustration

- 10. Forward Leaning the Trunk. Leaning forward and showing a sunken chest may be a sign of difficulty and frustration with the task at hand. At this point, the user may be close to giving up on a task or experience.

How to use these heuristics

The great thing about the ten emotion heuristics is that they are all 100% observable and cost-effective. The best thing you can do while learning these is to practice. Here is how I have learned to incorporate the emotion heuristics in every one of my interviews. These don’t have to be done step-by-step, but could be thought of that way!

- Memorize the different heuristics

- Practice the heuristics with others — both doing them and observing them

- While practicing with others, write down which heuristics you observe and compare notes

- Record each of your participants and assess heuristics AFTER the interviews — compare notes with a colleague on what heuristics you both found and at what points

- Observe and make note of heuristics during the interviews. See if you can dig deeper during those. Assess the interview after as well to see if you were accurate

- Rinse and repeat until you feel confident observing and noting the heuristics in real-time

Some things to note while you are practicing:

- Always record your participants during the interviews. Even when you are a “pro,” you might miss some instances. Make sure you can see their facial expressions in the recording!

- Have a colleague with you to compare notes (especially in the beginning)

- Take it slow! You won’t learn or notice these all over a short period of time

What can we do with this information?

There are a few different ways I like to use the emotion heuristics, and they all have really benefited my analysis of research studies.

- Observing behavior over words. What people tell you and how they act can be different. The emotion heuristics can give you an indicator of how someone is really feeling at a given moment

- Some negative emotion heuristics appear outside of the concepts that we are testing. This helps give an indication of where we might need to improve the overall user experience of the product, outside of what we are testing

- You can measure if there are trends with certain emotion heuristics across the experience. Are the majority of participants exhibiting particular emotions during one task or flow?

- If many negative emotion heuristics are surfacing during a task, flow, or experience, you can prioritize fixing that issue higher than others

- By identifying the different cues across the interview, you can rate whether the participant’s experience was overall positive or negative.

- Give scores to tasks and overall experiences, which can help with calling attention to issues and prioritization

Although it might sound simple, using these emotion heuristics can be quite tricky. You might get a participant who doesn’t display many expressions or a participant who displays too many at once to count. User research isn’t an exact science and you will never get the perfect participant. The best you can do is practice and observe these signals participants are putting out. They won’t be the answer to all your questions and, sometimes, they may lead you down the wrong path, but they are another tool to put in the user research toolbox.

—

If you liked this article, you may also find these interesting:

- ACV Laddering in UX Research: A simple method to uncover the user’s core values

- User Research Isn’t Black & White and how to navigate the grey area

- Benchmarking in UX Research to test how an app or website is progressing over time

- How to Assess Your Research Interviews: A framework to continuously improve

If you are interested, please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions :)

Should user researchers give feedback to teams?

Where does user research feedback start?

The other day, I saw a bad prototype. It came up during a design critique. We were going to start user testing that very prototype the next day. I wrote down my notes and mentioned it to the designer.

The problems I saw were:

- Typos

- Simple design flaws (different colors for the same hierarchical information)

- Information that made no sense in the context

For me, these were easy things to fix. I wanted to give the designer this feedback for two reasons:

- To make the design cleaner, and to encourage attention to detail

- To ensure we were getting the right feedback from the users

The second reasoning behind this, for me, is more important. When I present a prototype to users, I would rather not spend the precious time we have with them confused about easily changed information. Or information that doesn’t matter in the test. It can be a big waste of time, and participants can get stuck on these small inconsistencies.

What happened in this case? Unfortunately, the designs didn’t get changed in time. We tested the older designs with the issues I mentioned. While we did get some great feedback on the user experience, there was some time wasted on those smaller inconsistencies. I had to explain them and wave them off as small mistakes that don’t matter. However, it made the interviewing experience seem less productive and prepared. Almost every user recognized the changes I had asked to be made.

Regardless, again, we still received great information from users, but it felt clunky to explain away the prototype. Now, I know prototypes are supposed to be far from perfect, but this felt beyond the usual prototype spiel I give.

So, my biggest question in this case: is it okay for the researcher to request the changes I did? Or is it on the researcher to perform the interview in a manner where these inconsistencies don’t matter to the user?

When should user researchers give feedback?

This particular case made me question when, and at what level, user researchers should give feedback to our teams. I generally give feedback during the following opportunities:

- During the idea/concept phase

- During the prototype phase

- After a design is completed

- Synthesis from research sessions

I’m not entirely sure if this list encompasses every opportunity, but it was my starting off point. I don’t want designers or other team members to think I am an expert in UI/UX (or any other field, for that matter) or that I am overstepping boundaries.

Here is how I give feedback at each of these steps:

- During the idea/concept phase. I do my best to ensure teams come to me with ideas very early on in the development process so we are able to test the viability of the idea with users. When they come to me with ideas, they are generally solutions, rather than problems. I ask them to come up with the problem they are trying to better understand and the questions they would ask during to find out more information. Some teams have come to me with a fully developed idea, which I knew would not stick with users, or solve any pain points. In this case, I was new to the company, so I was forced to test it with users. It proved the point that it is important to do some upfront user testing before we come with fully built solutions based on assumptions. Now, when people come to me with solutions, I request they go back to the drawing board and start with a user problem, and questions they would like to ask.

- During the prototype phase. This is similar to the example I gave above with the prototype. I try to get a look at all prototypes before we put them in front of users. I will have the designer walk me through each screen, and I will point out any small inconsistencies. This gives the designer a second pair of eyes on the designs and helps ensure the design and flow make sense. Prototypes can still be “messy,” as in low-fidelity, but they need to make sense. We don’t want to waste time having users comment on small things that are insignificant to the usability test.

- After a design is completed. This is where the whole feedback concept starts to get tricky for me. Once a design has completed user testing and is off into the wild world of being “live,” what do we do? Since it was already user-tested, do we have the right to give additional feedback? For this stage, I will wait a bit and then follow-up with any feedback we are receiving on the particular design (or feature). If the design did not go through user testing, I will test at this stage and do a heuristic evaluation to give some additional feedback to the designer.

- Synthesis from research sessions. And finally, synthesis. Maybe for some, this is the most straightforward but, for me, it can get complex. We all talk about how synthesis is one of the most important parts of the user research role, but rarely is it discussed in full. At this point, how I understand synthesis is as follows: we digest and analyze the research sessions, and then give “actionable recommendations” on what should come next. What does this mean? Are we telling people what to do? What are we recommending? This brings me to my next point…

At what level should we give feedback?

Since the first three opportunities for feedback are much more straightforward, I will focus on synthesis for this particular case. I have the following questions when it comes to giving feedback (specifically targeting synthesis):

- What should we be producing? Action items/recommendations?

- What are the action items/recommendations?

- How far should we go with action items/recommendations?

I truly believe user research isn’t about giving people answers, it is about giving people tools to better contextualize something. We aren’t meant to “tell people what to do.” So, with this in mind, what are we supposed to be writing in terms of recommendations?

When I tested the aforementioned solution (which was a huge feature), it was glaringly obvious our users would not find it helpful or useful. And they would not pay for it. There were a few aspects of it they liked, but, by in large, it wasn’t sticking with them. They simply were not interested, and would rather have the company work on other features or improvements.

When I received those results, I wasn’t entirely sure what to do. The solution was already half-way built, and the team had spent a good amount of time working on it. I decided to give my honest recommendation: stop working on this immediately and pivot to working on other, more impactful, areas. I gave some ideas on how we could change the idea to suit our users better, but it should not be a high priority. I was lucky to have enough people on my side to be met with little resistance.

However, when it comes to these tests, I always wonder what level we should give this feedback and these recommendations? I often state the recommendations as problems instead of solutions:

“User is unable to locate the “pay” button or move to the next step” versus “move the “pay” button to higher on the page or make it a bolder color.”

This still gives enough flexibility for someone to make a better decision, without me telling them exactly what to do. However, as I mentioned, I also made an honest recommendation of not continuing on with a product. I’m not entirely sure what the balance is, but I am sure there is one. But I would still love to know…

How do you give feedback as a user researcher?

If you liked this article, you may also find these interesting:

- Burnout as a User Researcher

- User Research Isn’t Black & White

- Benefits of Internal User Research

- How to Write a Generative Research Guide

If you are interested, please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions :)

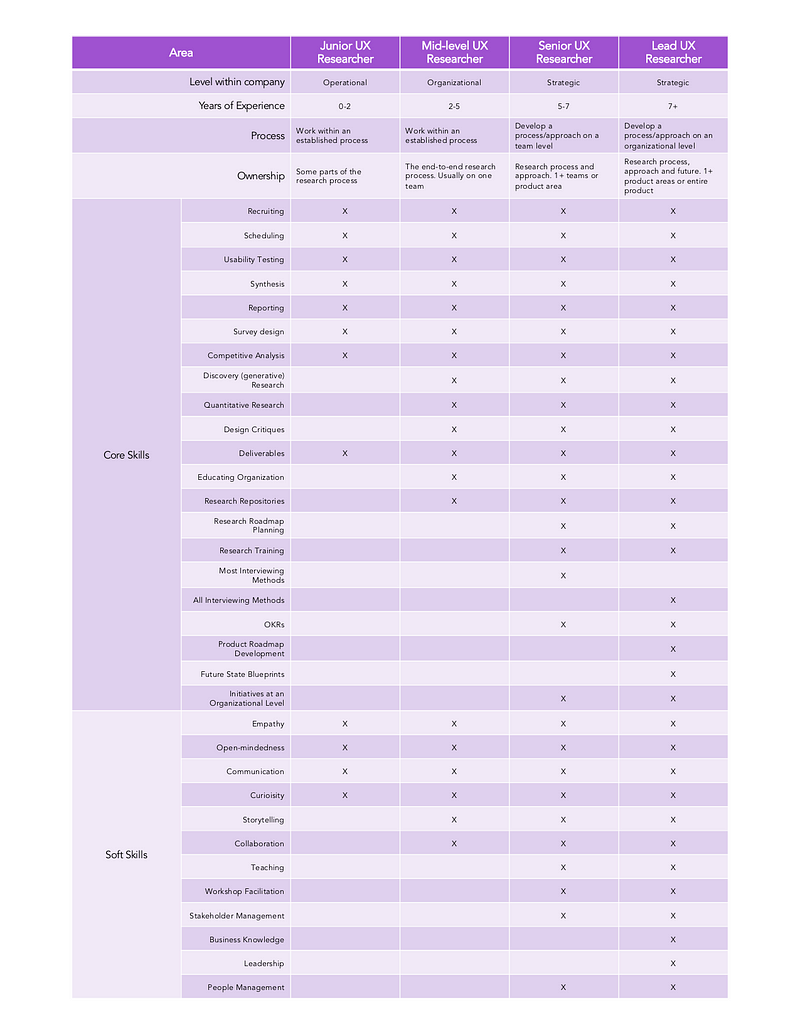

Assessing your user research career level, seniority, and path

Career paths are extremely important topics to think about, especially in the context of a more niche field, such as user research. While there is some information online, it is primarily for the broader field of UX and much more focused on the UX design career path. Planning the next 1, 3, or 5 years of your career is never easy. But trying to do so without a lot of guidance or mentorship can be even more difficult.

The reason I know this is because I have recently been trying to figure out what my next step is, and have also failed to plan effectively in the past. This lack of planning has led to confusing and less than ideal roles and situations. Knowing what your current level is, and where you want to go with your user research career, really helps you make sure you are in the best role for growth.

User research career levels

There are a few different levels of user research, and (fortunately) they generally follow the same kind of trajectory as other careers. I have also put a general amount of years of experience but this, of course, can vary. I have seen people in certain roles with much less, or more, experience than is generally “recommended.” I believe an employee’s skillsets and level of maturity are far more important in determining a career level than the number of years someone has been in the field.

I have also measured these against the following areas of impact a researcher could have on a company level:

- Operational: Deals with the day-to-day function of user research

- Organizational: Handles how the company understands and ingests user research

- Strategic: Aids the company in making strategic decisions based on user research

User researcher levels

- Research coordinator: Supports the product team throughout the research life cycle, including scheduling, recruiting efforts, participant communication, streamlining research operations and team communications

- Junior user researcher: Embedded in a team to carry out user research activities. They have some practical experience but need regular guidance and training to produce their best work and develop their skills. They generally work in combination with a more senior user researcher

- Mid-level user researcher: Embedded in a team and responsible for planning and carrying out user research activities. They are able to work independently on a team, without too much guidance

- Senior user researcher: Able to plan and lead user research activities in larger teams and on more complex services. They build user-centered practices in new teams and align user research activities with wider plans to inform service proposition. They may supervise and develop other user researchers to assure and improve research practice

- Lead user researcher: Leading and aligning user research activities across several teams. They ensure that teams take a user-centered, evidence-based approach to service design and delivery. They develop and assure good user research practices

- Head of user research: Leads user researchers in an organization and attracts and builds talent. They are an expert practitioner who can define and assure best practice, influence organizational strategy, and priorities, and collaborate with colleagues across a company.

Different career paths

There are two main career paths for user researchers, and they are similar to those of other industries. In general, you can go one of two paths:

- The individual contributor

- The manager

The biggest question I would ask when determining one of these two paths is to understand: “do I want to help others develop the skills I have?” or “do I want to continue to hone my skills as a research practitioner?”

As a manager, of course, you may still be able to engage in the more tactical side of the job (ex: actually conducting research), but usually, you operate as a people manager, mentor, and strategic partner. As an individual contributor, you will most likely be able to contribute at an operational, organizational, and strategic level. The biggest difference here is whether or not you are mentoring and managing others.

If you feel okay stepping away from the day-to-day and are looking to mentor others in the field, management might be your best bet. If you want to become a super expert in your field, I would stick with being an individual contributor. Of course, the best way is to simply try. As of right now, I have been a senior-level individual contributor and have finally decided to make the leap to management. Let’s see :)

How to assess your level

Now, these descriptions and charts are all generic. They have to be. There is no one description that will be perfect for all. Many user researchers have unique paths and experiences, so it is hard to make generalizations. However, for the purpose of this article, I do my best to help you categorize and see where you can grow.

Here are the steps I take when assessing my level:

- Audit my own skills. I always start by listing out all of my skills and my level of confidence in these skills (“low, medium, high” is totally fine). I also list the skills I would really like to learn next, that I find important for moving to the next level

- Look at the skills in the different levels. I then look through the skills in the level I think I am, and then the levels directly below/above. I also stalk people on LinkedIn at the level I think I am, and the surrounding levels. I see what their experience and skill sets are, and then compare that to mine. I also do a lot of networking and talking to researchers at all levels to get a more concrete idea. Actually talking to other researchers is the best way to do this!

- Consider my past experience. As I mentioned before, skills are one thing and experience is another. I always consider my past experiences, roles, and responsibilities. For example, when I was starting out, I was a UX Research intern but was expected to operate as a more junior/mid-level. With this, I was able to gather different skills and experiences that pushed me almost straight from Intern to mid-level. It is important to take this into consideration.

- Think about my level of maturity. This is especially important when you start to get into the senior/lead positions in the field. It is extremely important that you strongly consider how mature you are as an individual. More and more people will be depending on you on a consistent basis, and you will have much more pressure and feedback coming your way. It is okay if you have not yet had the training to best handle these situations, but they are very critical to consider when you move into these roles. You will also have a level of responsibility for others if you choose the management track

I recommend doing this at least twice a year, as it will give you a better understanding of where you are currently and where you can go in the future. Not only is this great practice to do for yourself but, if you are looking to go towards the managerial track, it will be great practice for your future reports!

What is another aspect of your career that is great to assess regularly? Defining your user research philosophy!

If you liked this article, you may also find these interesting:

- How to Assess Your User Research Interviews

- How to Break Into User Research

- A Week in the Life of a User Researcher

- How to Write a Generative Research Guide

If you are interested, please join the User Research Academy Slack Community for more updates, postings, and Q&A sessions :)

A week in the life of a UX Researcher

The Atypical Week of a Researcher.

I am constantly getting asked about what a typical day is like as a user researcher. And, to be honest, my answer is always “it depends.” I wanted to answer this question the best I could, so I decided to outline a week of my life as a user researcher. To be clear, not every week is like this, and they can vary from this.

Monday

8:30 — Leave for work and practice some German on the train

9:00 — Arrive at work and grab a tea

9:15 — Check and respond to any emails, such as recruiting participants confirming, and slack messages from team members.

9:30 — Squad meeting number one. We meet to discuss what is being worked on and anything that is coming up. The squad lets me know what research they will need in the upcoming weeks.

10:30 — Squad meeting number two. We meet to discuss what is being worked on and anything that is coming up. The squad lets me know what research they will need in the upcoming weeks.

11:30 — I create research plans for any upcoming research needed, and share it with the relevant squad so they are able to comment on the document, and add anything else they are interested in learning about.

12:30 — Lunch

1:00 — Squad meeting number three. We meet to discuss what is being worked on and anything that is coming up. The squad lets me know what research they will need in the upcoming weeks.

2:00 — Based on the needs from the squads, I will pull a customer list of our email subscribers and reach out to them, one-by-one, to see if they are interested in participating in a user research session.

3:00 — Generative research session with a customer

4:00 — Research synthesis for the generative research session, in which I review the session, record detailed notes and create a research summary to send to the relevant squads

6:00 — Check my email to respond to and schedule any new participant sessions.

6:30 — Leave work to go home.

Tuesday

8:30 — Leave for work and practice some German on the train

9:00 — Arrive at work and grab a tea

9:15 — Check and respond to any emails, such as recruiting participants confirming, and slack messages from team members.

9:30 — Answer any questions from the squad about the previous research sessions

10:30 — Half-day research synthesis session with a squad: we have finished speaking to seven participants for a usability test we have been working on for the past two weeks. In order to make sure we are all on the same page with next steps, we sit in a room together to discuss the different results, and decide on an outcome. I facilitate the workshop, bringing the team through the research insights, and helping them sort through the results with an affinity diagraming exercise, and HMW statements

4:00 — Generative research session

5:00 — Research synthesis for the generative research session, in which I review the session, record detailed notes and create a research summary to send to the relevant squads

6:30 — Quickly check email and leave work to go home

Wednesday

8:30 — Leave for work and practice some German on the train

9:00 — Arrive at work and grab a tea

9:15 — Check and respond to any emails, such as recruiting participants confirming, and slack messages from team members.

9:30 — Answer any questions from the squad about the previous research sessions

10:30 — Present the research findings and next steps to upper-management

11:30 — Chase the squads who haven’t responded to research needs to make sure they tell me what research is coming up, so I have enough time to recruit (it takes me about one week to manually recruit enough participants)

12:30 — Lunch

1:00 — Recruit more participants to make sure we have a backlog for any “surprise” projects

2:30 — Usability test with external participant

3:30 — Synthesize the usability test results

4:30 — Prioritization brainstorm: sit with one of my squad teams to prioritize upcoming ideas for the backlog

6:45 — Quickly check email and leave work to go home.

Thursday

8:30 — Leave for work and practice some German on the train

9:00 — Arrive at work and grab a tea

9:15 — Check and respond to any emails, such as recruiting participants confirming, and slack messages from team members.

9:30 — Office hours: I am free for any squad who needs questions answered, or wants me to help with research planning

11:30 — Team meeting

12:30 — Lunch & Learn: What is User Research — I help educate the company and any new hires on what user research is, and how they can get involved

1:30 — Internal usability tests on a concept we will test

3:00 — Budget proposal: I propose next year’s annual budget for research to upper-management

3:30 — Generative research session

4:30 — Research synthesis for the generative research session, in which I review the session, record detailed notes and create a research summary to send to the relevant squads

6:45 — Send a few more recruiting emails and leave work to go home.

Friday

8:30 — Leave for work and practice some German on the train

9:00 — Arrive at work and grab a tea

9:15 — Check and respond to any emails, such as recruiting participants confirming, and slack messages from team members.

10:30 — Full-day workshop on generative research sessions. During this workshop, all the squads get together to discuss the previously done 10 generative research sessions. I facilitate the workshop in order to help people more deeply understand our users, and also to help each squad prioritize their work. We make sense of the research through affinity diagraming, how might we statements and empathy maps. I follow-up with the designers in order to start building/iterating on personas and customer journey maps.

6:30 — Leave work to go home and enjoy the weekend.

All of this is based on a random sampling of a week to try to encapsulate what a user researcher does on a weekly basis. It doesn’t always look like this, and sometimes I have 2–3 generative research sessions a day, or even 5 internal usability testing sessions!

Jobs to be done personas

Focus on the job, and all else will follow.

There are so many different types of personas, it can sometimes make your head spin. And, oftentimes, people don’t generally like any of them. When describing personas, people use “useless,” “confusing,” “stupid,” and many other negative words. I have had people tell me to use them and others who tell me to avoid them…and, like most, people who throw their hands in the air, unsure of what to do.

Regardless, I have a soft spot for personas. I truly believe, with the right lens and mindset, they are a great tool to be used for innovation and decision-making. Personas are fictional characters that embody the typical characteristics of different user groups. See here: they are a fictional embodiment. We have forgotten that personas are a tool to be used, not the answer to all of our questions, or the solution to all of our problems.

How I use Personas

The reason I create personas is to help my teammates understand the story and the relevant context of our users. I’m not just trying to shove as much information as possible on to an A4 poster. I want to help my team make decisions with the information I give them. I believe, if we are mindful of how we use them, they can be excellent tools that can help guide teams towards better decision-making and innovation

What are the benefits?

- Set the focus

- Empower product and design to make better decisions

- Builds empathy for the users and promotes a user-centered mindset

- Make our assumptions explicit

- Keeps users at the center

- Show the realistic

- Helps to inform user stories

- Aligning the organization on the same language

Now on to Jobs To Be Done Personas…

First off, let’s start off with a small explanation of Jobs To Be Done:

Jobs To Be Done encompasses the concept that users are trying to get something done, and that they “hire” certain products or services in order to make progress towards accomplishing goals. Usually, we all want to be better than we are in a given moment. We all have goals that lead us closer to our ideal self. So, we will look for, and purchase, certain products or services when our current reality does not match what we want for the future.

With Jobs To Be Done, we are completely solution-agnostic. We aren’t even thinking about our product or any products in general. We are focused solely on people’s motivations and how they act. We try to identify their anxieties and the deeper reasons of why they act the way they do, and why they respond in certain ways.

For instance, if we have a travel product that allows people to buy all types of travel tickets online (bus, car, plane, scooter, you name it), we focus our research on how people are using this website/app and how they buy tickets online. However, when you think about it, people didn’t buy tickets online in the past, so this kind of platform didn’t exist back then. And in ten years, there will probably be a new way to buy tickets we don’t even know about yet.

The point is, people still need to travel for various reasons. That job remained stable throughout the years, and the solutions created for it have changed. People will use different products that allow them to get their job done in a faster, better way.

So, if you are just focused on the best ticket buying experience, you will be relevant for some time, but, eventually, competitors will overtake you. Instead, we need to focus on the job people are trying to accomplish: getting from one place to another in the fastest and easiest way possible.

If you look up Jobs To Be Done Personas, you will often find articles called: “jobs to be done versus personas.” When you put these two concepts together, it is usually an either/or conversation. They don’t seem to be able to exist together, in harmony. Most people believe you either do JTBD research or you have personas. I, however, disagree. I believe there is space for a JTBD persona.

How to Create JTBD Personas

Creating JTBD personas is fairly similar to the process of creating other personas. There is a lot of research, analysis, and synthesis. Below is how I created our first JTBD personas.

- Do JTBD research. The first, and most important step, in creating these personas is to do the foundational research. I interviewed around 20 people in this style of interviewing before I started to come up with the concrete personas. Some people say you can make them with less, some only with more. Either way, it is whenever you feel comfortable enough with the data you have gathered. Keep in mind, these will keep changing, so nothing is set in stone. If you have never done JTBD research, feel free to read my guide: https://dscout.com/people-nerds/the-jobs-to-be-done-interviewing-style-understanding-who-users-are-trying-to-become

- Define the goal of the persona. What is it that you are trying to accomplish with your persona? There are several different goals you can have when creating a persona. Below are the various reasons I have created them:

- Show colleagues who our customers are

- Highlight the behaviors of user groups

- Present high-level motivations of users to highlight the why behind certain behaviors

- Tell a story of a user’s life and how they operate when they want to accomplish a certain task

3. Decide on the information to include. I always do this before synthesis so I know what I am looking for when I comb through the data. JTBD personas include slightly different information than what I would put in more “traditional” personas.

- Motivations. I believe motivations are the most important part of the JTBD interviews, and the most important information to include in the personas. JTBD highlights the motivations behind our actions. I separate motivations into three different categories: ideal self, experiential self, and social self.

Ideal self motivations: What is getting the person closer to their ideal self? What are they doing to get there?

Experiential self: What is that person trying to experience in order to get closer to the ideal self? How do they want their environment to impact you?

Social self motivations: How is the person trying to be seen by others? How do they want their relationships to function and get them closer to the ideal self?

- Values. What does the person, at a high-level, value in day-to-day life? What are the concepts or ideas that are important to them?

- Needs. What does the person need on a day-to-day basis? What is important for them to have to accomplish their goals?

- Pain points. What is a painful experience for that individual? What do they try to avoid? What causes them anxieties?

- Goal (or job). What is the goal (or job) they are trying to accomplish? What is the outcome they would like to achieve?

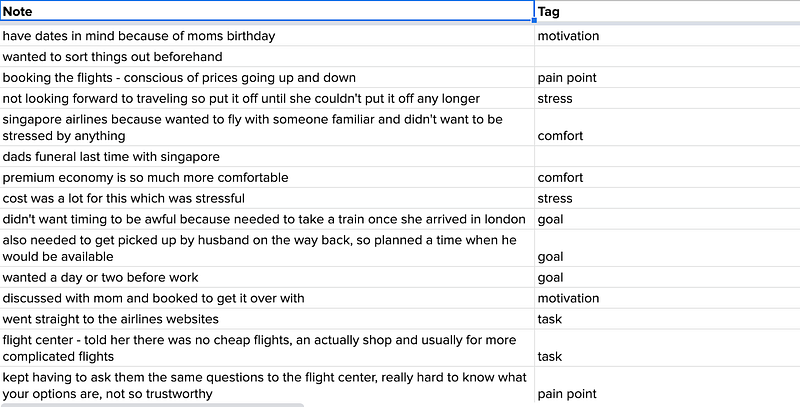

4. Pull together the information. Read through all of the transcripts and notes that you have gathered from the research. One thing I do is tagging each important transcript line with one of the above points (motivation, pain point, goal, etc.). See an example below:

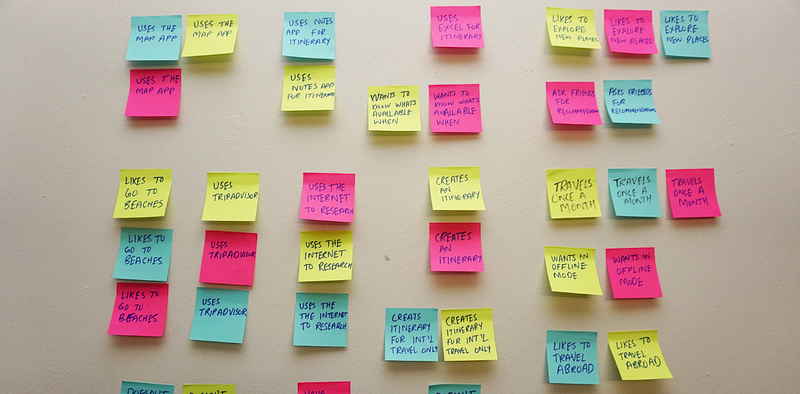

I then will create an affinity diagram with all the research I conducted and once I am done tagging. This is where I group all of the similar patterns I hear and cluster them into categories, such as motivations, values, pain points, etc. See an example below:

5. Outline the persona. Create version one of the persona. Include all the information you think might be relevant. Again, we are trying to help teams understand motivations of why someone acts the way they do, why they might use a product, and also tell a story of that person.

6. Design the persona. Putting this information into a visual format is the last step. Try not to do this before you have all the information together. Additionally, you don’t have to go crazy with graphics, as they usually aren’t helpful for a team. There are these bars that indicate people’s personality traits on a spectrum, and they are infuriating to me. They aren’t beneficial at all to a team making a decision. Keep the persona simple.

My most significant piece of advice when creating a persona: don’t just blindly use one of the many templates available. Although some may be beautiful (while others are undoubtedly ugly), they won’t serve you. First, come up with your goal and the relevant information needed for that goal. Then start creating the visual.

My second piece of advice: don’t make anything up. Delete all false or dramatized information. It will only get in your way when making decisions and could lead the team astray. You want your personas to be based on real user data.

I will do a more in-depth case study highlighting what this might look like with a real-life example. Until then, I hope this was helpful!

How to Break into User Research

Becoming a user researcher is not easy.

One of the number one questions I get every week are people asking me how to break into the field of user research from another role or right after graduating. I speak with people from all different disciplines, some closer to user research, such as marketing, psychology or design, and others further away, such as accountants or writers.

One thing I love about user research is that the skills you need to break into a field are about relating to and empathizing with humans. For me, it has been one of the most rewarding jobs I could ever have imagined. Through user research, I can have a positive impact on both users and team members. Another great thing? I genuinely believe most people can become great user researchers, without paying loads of money for a degree or certificate.

To prove this, here is my story of how I broke into this field and some tips to go with it.

How I got into user research

Getting into user research was one of the least straight-forward paths I have taken, and that is often the case for most people breaking into this field. There is no one magic course to take or one perfect path that will guarantee you an entry into any user research job. It is one of the more difficult specialties to get into because of the indirect pathway, especially when even the entry-level jobs seem to have a mountain of requirements. A lot of my students ask if they should go back to school to get a Masters. With this degree, they believe there will be a higher chance of them getting noticed. That isn’t necessarily the case.

Most of the time, I would, quite honestly, say no, you don’t need to go back to school and get your MA. The only exception is if the degree encompasses other interests and potential career paths. For example, one of my students is potentially interested in becoming a user researcher, but also might end up in policy research. In this case, it might make sense for him to pursue this degree. Aside from that case, I would argue that it is not necessary to go back to school to get into user research.

I was able to get into user research through an internship in New York City. I had just finished my MA degree in psychology (yes, I know I said you don’t need a higher degree to get a job, but wait for it), and decided I didn’t want to continue with pursuing my Ph.D. Instead, I wanted to join the world of user research. My MA degree was in clinical psychology and came with some knowledge of statistics. The role I finally received was as a user research intern, with a qualitative focus, at a tech company. I had never worked at a tech company before, and let me tell you, my Master’s degree could never have prepared me for the experience.

How did I go from an MA in psychology to a UX research role?

I took a few different steps when I started looking at and applying to different UX research positions. Below is (what I remember) of my crazy process of diving into this unknown world:

- Look at 100 user research job postings and scour the responsibilities. I found the most common to be conducting research sessions, usability testing, note-taking, recruiting. Then I tried my best to make my previous experience sound as relevant as possible in this context. It wasn’t easy. Yes, I had experience recruiting participants and some interviewing experience, but usability testing was out of the realm of my knowledge, as well as understanding how a tech company worked.

- Stalk all the well-known user researchers on LinkedIn. I read about their day-to-day descriptions of what they did. Reading their responsibilities helped me understand the different skills I needed, outside of what recruiters posted on job descriptions. It also helped me know if this was something I wanted to do with my life

- Find companies that have an established research team or a senior researcher. This way, you can learn. I was the only UX researcher at my first internship and had to leave after eight months because I needed a mentor. I was lucky enough to find one in my next role. He helped me take my researching skills to the next level and is one of the reasons I have succeeded in this field

- Apply to a million jobs. I think I applied to something like 67 jobs when I was first starting. Some of them, I would have never got in a million years, but it was worth applying. What is the worst that can happen? You never hear from them again, or they say no thanks. I disregarded some of the “requirements” and I think you should do the same. In the beginning, I looked at and applied to roles where they wanted 1–2 years of experience. Even if they say they want an MA or MSc degree, APPLY ANYWAY. As Dory might say, just keep applying.

- Go to meetups and meet user researchers. Connect with others in the field and ask them how they got into user research (there are many weird ways). Networking is also fantastic for finding internships or potential opportunities. Hate networking? Check out my guide to networking as a user researcher.

- Many positions were looking for a portfolio or a case study. Now we get to the hardest part. I had NO idea what a case study for user research was. After some googling, I understood this was an example of work. Well, I hadn’t done any UX work that I could show. I started working on a few personal projects. This, right here, is my number one tip: If you have never done user research before, the best thing you can do is read up on it and START DOING RESEARCH. Pick an idea and try to map out how it would work at a company. I created a competitive analysis, wrote a research plan, did some discovery research, card sorting, usability tests, and came up with some insights. Pick something you are interested in and do a research project on this. I post weekly prompts on Medium and feel free to respond to those.

Practicing user research is an essential part of creating a portfolio and getting “experience.”

Yes, I honestly look back on those pieces now and laugh, BUT, I got an internship, and a few other interviews because of those small projects. I put in a lot of amount of effort into three case studies, and it helped me when I went to apply and interview. They weren’t perfect, not even close, but they showed initiative and my passion for learning and being a part of this field. What else do you want for an intern or junior role?

I have some final thoughts on why a degree won’t help you as a user researcher. The most critical and best way to learn user research is to be in an environment with user research. It is absorbed by practice, not by theory. Unfortunately, at this moment, user research is not being taught this way anywhere. There may be aspects of this in an MA program, but I believe the best thing you can do for yourself is to get into an environment in which you are learning user research through doing and observing. MA programs will give you a theory to work off of, but the practical experience isn’t there.

I prefer aspiring researchers to spend two years trying to get into an apprenticeship or internship than spend two years learning, and then try to get into an entry-level research position.

Check out my website for some resources to get you started on user research (such as templates and guides): www.userresearchacademy.com.

As always, feel free to leave any questions or comments.

User research isn’t black & white

And how to navigate the grey area.

Recently, I was thinking back to when I started my career in user research. I was a Google machine. I looked up and read everything I could about the field. What I found most prevalent were the “User Research Best Practices” lists. There were many of them floating around the internet, but they all had something in common. They all told us what not to do.

I sat there, with my head full of the knowledge of what not to do in a research session, but didn’t have nearly as much information about what I should be doing. How was I supposed to navigate a messy situation? The negative reinforcement was doing nothing to move me forward, but instead creating an air of fear that I would mess up and get fired for ruining a company’s strategy.

Still, after many years in the industry, I continuously come up against this concept of all the things we are doing wrong in the field. The thing is, I agree with them. It isn’t as though I believe we should be leading our users and asking future-based biased questions during our interview sessions. However, the world is rarely so black and white, and companies are rarely so easy to navigate with a list of best practices. Oftentimes these best practices go out the window, given a stakeholder, situation or uncertainty with how to tackle something. So, instead of speaking in these black and white manners, let’s acknowledge and embrace all the grey in this world of user research.

Things we are doing wrong (or the deadly sins):

- Asking future-based questions

- Asking yes/no questions

- Leading the user with biased questioning

- Ignoring what the user is doing and placing too much importance on their words

- Asking double-barreled questions

- Not being open to the user’s answers

- Interrupting participants

- Speaking too much during the interview/filling the silences

- Validating concepts from upper-management

For real though, and maybe I shouldn’t be honest about this, but sometimes I commit these sins. Sometimes I ask yes/no questions to get a conversation started. Sometimes, in a moment, I ask a biased question and do my best to backtrack. I don’t think it is realistic to juggle all of these points and have a natural conversation at the same time. In addition, some of these best practices are extremely vague and don’t offer much guidance in the “correct” direction.

The problem I have with these best practices

Again, so I don’t seem like a crazy user researcher, I do think we should avoid pitfalls and use the best practices. However, many of these best practices are constructed as if we live in a perfect world of black and white. Very rarely are situations, especially those in user research, black and white. In fact, they are largely grey. And that is where I struggle with these lists the most.

User research isn’t, and will probably never be an exact science. We can’t always be perfect, and flawlessly execute a research session. We are humans, not robots, and I think that is 100% fine. We bring a level of empathy and perspective that would otherwise get lost.

Maybe some people call this bias, but I think it allows us to interpret research in a human and empathetic way.

Since the field of user research is so new and often misunderstood, we can get backed into a corner by stakeholders wanting specific questions to be answered. And also stakeholders who want specific answers to questions. Rarely are we working in an ideal environment for the best user research practices.

The thing is, conversations are h̵a̵r̵d̵ nearly impossible to predict. Trying to construct the perfect interview may end up making participants feel uncomfortable since it could feel very contrived. Either way, we always run risks. Risks are inherent when you bring two people together to unravel thoughts or perceptions.

An example: subscription box

Say you are working for a tech company that specializes in selling computer parts. You have identified a huge portion of the user base are gamers, who are constantly modifying their laptops, or building new computers for themselves and friends.

With this knowledge, stakeholders want to start a monthly subscription box with cool computer parts and coupons to various popular games. They essentially want you to validate this hypothesis as quickly as possible to push out this product. In the best terms: they want to roll out this product as quickly as possible, without pushback.

In this scenario, you are faced with the following challenges:

- Managing stakeholders expectations

- Asking about potential future-based behavior

- Predicting whether or not a user would buy something

- Forcing the user to think about a specific solution (subscription box)

- Asking potential customers about the price they would pay for such a service

- Getting a yes/no answer to interest in this specific solution

That list violates much of what we, as researchers, “should not” do. But, these scenarios are our day-to-day reality and happen more frequently than ideal situations.

So…what can we do in a situation like this? Here is my approach:

- Set expectations for stakeholders on what user research can do, and what it cannot do. I make it clear that user research is not used to validate what we want, but to explore whether or not a hypothesis is valid. We might not hear what we want to hear. Warning: they may not listen

- Recruit current users who have subscribed to a recurring subscription box in the past. If you can’t find any, that may be a sign that this is not for your target audience. In the case that you must run the study anyways, find users who know of people who have subscribed to a recurring subscription box. If this isn’t possible, recruit current users

- If you are, in fact, able to get users who have subscribed to a recurring box in the past, fantastic! Your job just got easier by mitigating the problem of asking for future behavior. In this case, the best way to predict future behavior is through past behavior. Whenever I am trying to anticipate whether a user will or won’t use a certain product, I ask them about their past experiences with something similar. I ask what they enjoyed about a similar product, and what they would change. This gives a good indication of whether or not we are going in the right direction

- If you are not able to get users who have subscribed to a recurring box, you are in a bit more of a tough spot. For this, I try to relate the question to something similar. Have they signed up for any recurring service? I try to mention common services, such as a gaming subscription (ex: World of Warcraft), Netflix or Amazon Prime. This way I can at least get a pulse on what they think of the above. This may give me some insight into how to structure the service. I then would ask them if they have any bought any computer part (or whatever we would offer) packages for themselves or others. This would then give me an idea of what they were buying together

- If I could find no current, churned or potential users who did any of the above, well, then I would caution against the idea in general. I would tell stakeholders I don’t believe there is a market fit in this particular area, with this particular audience. If they forced me to do the research (which some have), I would have to resort to asking future-based questions. At the end of the day, they are paying me. When you get backed into a corner, and no one heeds your warnings, there is little more you can do. I have refused to do the research, and it resulted in my freelance gig ending early. Spoiler: the product I was asked to do research on failed.

- After asking users about their past behavior (assuming we found users who subscribed to recurring boxes), I then pry into as many details as possible:

- What is the box like?

- Do you know anyone else who receives this box? Have you ever given it as a gift?

- How often does it come?

- What are the contents? What is the quality of the contents?

- What do you love about? Hate about it?

- How would you improve it?

- Do you currently still subscribed to it? Why/why not?

- What would make you stop subscribing to the box? What would make you a lifelong customer? (Yes, future-based, but still interesting to think about)

- What is the price? How do you feel about this price?

This information will give me insight into how we could structure a potential subscription box that would appeal to this audience. Of course, user research isn’t a straight answer and doesn’t guarantee success, but it gives us a direction to go with.

7. Asking about prices is always difficult and, in the example I mentioned, I ask for the price of a comparable product. This is the absolute best I can do, even if I am relating the computer subscription box to Amazon Prime, it is better than flat out asking someone how much they would pay for a hypothetical subscription box. Even if the two services aren’t equal, it gives me an idea of how they think about price and value for a service

8. I must admit, and maybe this is a sin, but I do float the actual idea by users at the end of an interview. I like to gauge their initial reaction when I mention an idea, such as the computer subscription box. I don’t base my entire interview on how they react to the idea, but it can give a decent indication of interest level. If you’re lucky, you get some really honest users, although most aren’t because of a variety of psychological phenomenon

9. Once I mention the idea to users, sometimes I will ask point-blank: would you use something like this? Would you subscribe to something like this? What would you expect it to be like? What would it contain? How much would you pay for it? In the end, I ask all the wrong questions because I spent fifty-five out of sixty minutes doing my best to ask all the right ones. Just because they are the best questions doesn’t mean they can’t give us any information. Again, I don’t base my research findings on these last five minutes, but I try to dig as much as I can out of the users, even if it is hypothetical

10. If I found very little interest in subscription boxes, both past and the potential current, I have to present a “failed” idea to stakeholders. Whenever I do this, there are two ways it can go: they listen or they don’t. In any case, I never just present that the project failed and that there is no way such an idea would ever work. I present alternative routes or ways to improve the proposed offering. At least, with this, there is a higher likelihood the stakeholders will listen to some insights and make the product as best as possible

Ultimately, what we are trying to do when asking about a future product is to understand the user’s mental models. How do they currently think about subscription boxes, specifically those for computer parts? How do subscription boxes fit into their day-to-day life? How do they enhance it? Or take away from it?

This is our goal, and we must remember it. Nowhere in that goal does it say you must never utter yes/no questions, or that you must never try to predict future behavior.

I would love to hear more about what you would do in this situation — my perspective only goes so far and I am excited to hear how others would tackle this.

Let’s adapt our research situations to realistic guidelines

We’ve established that user research tends to sit in a grey area, so what can we do in the future. The purpose of this post is to make sure we all know, especially those just beginning in the research field, that things won’t always be perfect. You may have to do research you don’t believe in and I am sure you will have to deliver results that are directly opposite of what stakeholders want to believe.

Instead of attempting to force user research to fit neatly into a chaotic environment, or trying to make an inexact science perfect, let’s allow user research to continue being what it is: human-centered. We don’t need user research to be perfect and we don’t need to always be the perfect researchers. What we do need is to remember our goal, and use whatever we can to get to that goal. Ultimately, it is about the users, not the practice.

Weekly UX Research Prompt #6

The One About How People Set Goals

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement:

How can we better understand the way people set and stick to their goals?

Project brief:

Your client wants to understand better how people set and stick to their goals. They want you to focus your research on people who have set a goal in the past six months and have followed it through or have not. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people set and stick to their goals to help them to start designing a relevant solution

How would you approach this problem?

How to respond

If you respond on Medium, make sure to use the tag “weekly UX research prompt” so we can find each other’s projects!

You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

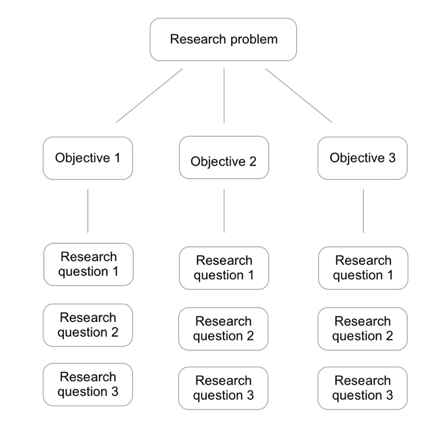

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

Weekly UX Research Prompt #5

The One About How People Organize Their Wardrobe

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement:

How can we better understand the way people organize their clothing?

Project brief:

Your client is a retail platform that wants to understand better how people organize their wardrobe. They want you to focus your research on people who purchase new clothing regularly (at least once a month) and care about organizing their closet. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people arrange their wardrobe to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

How would you approach this problem?

How to respond

If you respond on Medium, make sure to use the tag “weekly UX research prompt” so we can find each other’s projects!

You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

Weekly UX Research Prompt #4

The One About How People Get Around

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement:

How can we better understand the way people find their way around a new city?

Project brief:

Your client is a tourist agency who wants to understand better how people find their way around a new city. They want you to focus your research on people who have traveled, at least once, to a new city in the past six months. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people navigate a new city to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

How would you approach this problem?

How to respond

If you respond on Medium, make sure to use the tag “weekly UX research prompt” so we can find each other’s projects!

You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

Weekly UX Research Prompt #3

The One About How People Communicate

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement:

How can we better understand the way people communicate with each other?

Project brief:

Your client is a messaging platform that wants to understand better how people communicate with each other. They want you to focus your research on people who use platforms such as iMessage, WhatsApp, and Facebook Messanger to communicate with others daily. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people interact with each other to help them to start designing a relevant solution.

How would you approach this problem?

How to respond

If you respond on Medium, make sure to use the tag “weekly UX research prompt” so we can find each other’s projects!

You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

My step-by-step user recruitment process

And don’t worry, I don’t have a high budget.

Honestly, recruiting sucks. It is one of the most challenging, time-consuming, and tedious parts of my job. Every time a research project comes across my desk, I sigh internally thinking about the recruitment process, especially if there is a tight deadline.

Since the responsibility of recruiting will never entirely disappear, I decided it was time to implement a process. I wanted to make recruitment as easy as possible through a standardized method and with as many templates as I could. My goal was to make recruitment mindless, and something I could do on the fly, in between meetings.

Of course, not every part of recruitment can be streamlined, especially the first parts of brainstorming about which participants are best. I tend to take more time in the beginning stages to ensure the right participants are selected to get the most optimized research results. Below is my thought process before I even begin writing an email to potential participants:

Before recruiting

Approximate your user

Before we even start recruiting, we have to understand who our users are so we can optimize our recruiting efforts. Talking to the right people is a fundamental part of doing proper research. If you don’t end up talking to the “right” people, your research may result in a complete waste of time and effort. What are some ways to do this?

- If you don’t already have personas or a target audience, take a day to sit in a room and define your target user. Bring in internal stakeholders that may have a good idea of who the target user will look like (such as marketing, sales, customer support), and come up with proto-personas. These are, essentially, wireframes of personas that consist of hypotheses about who your user is, and are a great starting point for who you should be talking to

- Look at competitors similar to you, and recruit based on their audiences. You can even recruit people who use the competitor’s product, and during the interview, ask them how they would make it better — a bit of a bonus!

- Sit down with the team who requested the research and ask them what type of participants and information they need. Is there a particular behavioral pattern? Is it necessary they have used your product (or a competitor’s product)? Do they need to be a certain age or hold a specific professional title? Gathering this information will ensure you write a great screener, which will collect you the best participants

My Step-By-Step Recruitment Process

Once I have my screener survey written, I am off to the races. Well, the slow races. I will take you through a sample project I recently, to illustrate how I am currently recruiting participants. And, as I mentioned, the budget is small.

Sample Project: We want to test a potential product concept idea with 7–10 users of our platform. Ideally, they will have traveled three or more times in the past three months, and have bought tickets through our website or app. Ideally, this research will be completed and reported on in three weeks.

- Approximate the user. Since this particular project came with predefined criteria, it was easy for me to set the underlying demographics. We needed a mix of our current users for a product idea. Recently, we had decided to focus on a slightly younger demographic, so I included that strategy in my decision as well.

- Create a screener survey. Once I had the basic idea of who I wanted, I went ahead to start forming questions to get me the right participants for the project. I knew it had to be people who traveled three or more times in the past three months, and who have used our website/app to do so. I asked for demographic information, such as age, gender, and income, to understand how different users interact with our website/app. I then put this on Google Forms to easily send a link for people to fill out, which is free! See my example screener here.

- Pull newsletter subscriber emails from the CRM. Since I now work in the EU, GDPR rules are more strict than in the US. I can’t merely spam people who use our website/app. To get around this, I work with the email marketing team to pull newsletter subscriber emails from our CRM. When users sign up for our newsletter, they give us the right to contact them for user research sessions.

- Individually email users screener survey. With these emails in hand, or rather, anonymized on my computer, I set aside a large chunk of time to email each user. Since we can pull up to one thousand emails at once, I usually leave this task for the later afternoon, when my brainpower is already going downhill. In this email, I include a link to the screener survey, why we are contacting them, and, of course, compensation.

- Post a recruitment survey via HotJar. We were fortunate enough to get a business subscription to HotJar finally. They have a portion of their product dedicated to recruitment surveys, which pop up on the website. I include the screener survey there.

- Respond to any email inquiries. My Google form responses come in nicely to Google sheets, where I can see all of the information beautifully laid out. For everyone who “passes” our criteria needed for the study, I reach out to them with the session information, a consent form, and reiterating compensation. For those who do not “pass” the criteria for the particular study, I try to fit them into another research project. Also, keep an eye out for any questions potential participants might ask.

- Email calendar invitation. I use Google Calendar to send requests. I always double-check the timing and keep a consistent format for the subject of the calendar invite: Participant name x My name: company name feedback session. Within the calendar invitation, I reiterate the vital session information (how long the session will be, my email, etc.) and include a link to a Zoom meeting. I make a separate calendar invitation in which I book a conference room and invite all my colleagues.

- Email a session confirmation 12–24 hours before. The probability a participant will attend a research session goes up if you email them a reminder 12–24 hours before the meeting. In this email, I reiterate the necessary information, including a link to the Zoom conference room, and the consent form if they have yet to fill it out.

- Always send a thank you email. Regardless of compensation, or anything really, I always send a thank you email to the participant no more than 24 hours after the interview. In this email, I include specific topics we discussed, as well as the compensation voucher. Additionally, I encourage them to reach out to me with any questions or feedback in the future.

See all of my recruiting, scheduling and thank you email templates here.

Although it is still time-consuming, I have managed to decrease the amount of time I spend recruiting. In my case, the email templates have been especially helpful in speeding up the process. In the time since I started, I have managed to convince the team to invest in some great time-saving (and free/cheap) recruitment tools:

- Calendly

- Doodle

- Google Forms

- Typeform

- Zoom video conference

- HotJar

As tricky as recruiting can be, it isn’t impossible with a tight budget, or as a team of one. Just hunker down, create some streamlined templates, and enlist your patience.

Weekly UX Research Prompt #2

The One About Pet Adoption

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement:

How can we better understand the way people adopt a pet?

Project brief:

Your client is a non-profit animal shelter who wants to understand better the process people go through when trying to adopt a new pet, specifically in the digital space. They want you to focus your research on people who have chosen a pet in the past 1–2 years. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people adopt pets to start designing a digital solution relevant to users.

How would you approach this problem?

How to respond

If you respond on Medium, make sure to use the tag “weekly UX research prompt” so we can find each other’s projects!

You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

Weekly UX Research Prompt

Practice your user research skills

The first thing I tell people who are trying to learn or improve at user research is to practice. Practice, practice practice. Write research plans and scripts. Conduct practice interviews. Generate ideas on how you would help solve problems at a company. Always be practicing.

I employ this in my day-to-day life. I am a fiction writer and, I know, the best way to write is to write every single day. I have to practice writing to be a better writer. I generally do this by responding to a daily writing prompt. It doesn’t have to be perfect, but it empowers me to get some words down on to a page every day. And that is what makes you better.

The other night, an idea popped into my head. I so value the concept of daily writing prompts, so why don’t I try to apply that to user research?

The Idea

I want you to help you think about and practice user research more realistically. These prompts will allow you to do several things:

- Create a fundamental user research portfolio piece

- Practice for a whiteboard challenge

- Think about how you tackle problems

- Make you think on your feet

- Get experience outside of your day-to-day

- Flex your creativity

I will try to leave the prompts as vague as possible. You can do as much or as little as you want for each prompt. A full-blown research project is time-consuming, but just writing out some ideas for the prompts can also be helpful. Feel free to use the prompt to do the following (or more):

- Problem statement: What is the research project?

- Research objectives: What are you trying to achieve?

- Methodology: How did you do the research?

- Participants & recruiting: Who did you talk to?

- Interview guide: What questions did you ask? What was the flow of the interview?

- Competitive analysis and heuristic evaluation

- Synthesis and analysis techniques

- Insights from the interviews, such as quotes and affinity diagrams

- Generate outputs, such as user personas and customer journey maps

- Report any usability testing you did

- Next steps

If you have other ideas on how you would like to use these prompts, please share them with me so I can add them!

My offer

I believe we also improve by getting feedback from people. Use the tag “weeklyuxresearchprompt” on Medium or comment with a way for me to access your project (especially if it contains sensitive information). Every week I will pick 2–3 projects to review. What does this mean? I will spend about 30 minutes going through the project and giving you as much detailed feedback as possible. If you have a particular area you need more help on, just let me know beforehand.

I will post a user research prompt every Monday. Please give me feedback as I try this idea. I want this to be beneficial for everyone, and I am more than happy to iterate to make it better for all.

This week’s prompt:

Problem statement

How can we better understand the way people travel?

Project brief:

Your client is a leading travel brand who sees new opportunities emerging in the digital space around how people plan travel. They want you to focus your research on one group of the travel experience, either leisure travel or business travel. The client expects you to deliver insights on how people travel, in order to start designing something relevant for users

How would you approach this problem?