Asking about the future in user research

And why this method never works out well.

It is a tried and true saying: “never ask participants what they want” or “never ask about future behavior.” Why is this?

Let’s deviate for a second: 51 million Americans waste $1.8 billion dollars on unused gym memberships (Source). About 67% of people who sign up for the gym don’t go, yet they still signed up. They had every intention of going, but they didn’t. They failed to correctly predict their future behavior. This is why, as user researchers, we never ask about the future. Yes, gyms are still making money, but the fitness industry is worth about 80 billion US dollars (source), and is a very well-marketed field, which the same can’t be said about most companies trying to deliver paid-for features/memberships.

The only thing that can predict the future is the past.

The problem we face

User researchers constantly face this conundrum: we are expected to foretell the future of our users, to predict whether a user will pay for something, or even simply use something. All the time, I field questions from colleagues: “can you ask how much they would pay for this feature?”, “can you figure out how often they would use this feature?”, “can we gauge how much interest they would have in this new feature we are thinking about?”

As the voice of the user, and my desire to improve the world for, both, users and businesses, I walk a thin line between trying to ensure products increase revenue while making the user’s life more delightful. I don’t want users to create and pay for something they aren’t using or getting value out of. To me, that is a bit too much on the side of dark UX. I would rather be a part of something that makes the business money, but also provides tangible value to a user. I want the users, as well as the business, to have cake and eat it too.

Where asking about the future fails

Regardless of good intention, sometimes it can be really easy to fall into the future-based question trap. You want to get answers for your team, you want to give the guidance and direction, or else user research might be deemed as “useless” (it has happened). Not only are future-based questions completely unreliable and hypothetical, they can be quite uncomfortable for users to answer, and may lead to some social desirability bias.

Everybody has an aspirational self, and oftentimes, they lie to themselves and others because of this.

I have seen a wonderful example, which I have fictionalized:

Researcher: Okay, cool, so would you like an app that combines booking you a plane, a hotel as well as securing you a person who could dog-sit while you are away, or maybe just take your dog on walks…or, if you don’t have a dog, someone who house-sits and waters your plants?”

Participant: Um, yeah, that would be really nice.

Researcher: Awesome, so you would use that kind of app

Participant: Yeah, I think I would. It would help me out

Researcher: Cool, and how would that work or benefit you?

Participant: Well, I’ve never really thought about this…so just let me think…

There you go. “I’ve never really thought about this.” That is the golden nugget no one really wants to hear, but is extremely important. Yes, the participant said they would use an app that would, seemingly, make their lives easier, but they. have. never. thought. about. it.

Yes, there is a universe in which this particular service could be a hit, but there are a lot of risks associated with approaching solutions in this way. I’m in no ways trying to dissuade people from taking risks, sometimes it is necessary, but I would like teams to gather more reliable data before taking the leap.

it is hard, but possible. Researchers have to work a bit of magic.

How user researchers become psychics

As mentioned above, the past predicts the future. Instead of asking users how often they might use a feature, or how much they might pay for something, we have to reference their past. I have an exercise I commonly recommend to students, where we take future-based questions, and turn them into question about the past.

First, what are future-based questions?

- Would you use [feature/service/product/app]?

- How often would you use [feature/service/product/app]?

- Would you buy [feature/service/product/app]?

- On a scale of 1–10, how likely are you to buy [feature/service/product/app]?

- How much would you pay for [feature/service/product/app]?

- Would you pay X for [feature/service/product/app]?

I know I said these questions are bad, but a famous quote from Howard Schultz, former two times CEO of Starbucks should help highlight this concept:

If I went to a group of consumers and asked them if I should sell a $4 cup of coffee, what would they have told me?

Cool, great point, and I obviously agree. So how do we turn the future into the past. Just a note here, people may still lie when you ask them about the past, but it is still a much better indicator than asking them to predict their own future behavior.

How to predict the future from the past

Let’s use an example here. One of the easiest examples is a membership or subscription. I’ve always want to start a subscription box with stationary, based on user’s upcoming celebrations (so, I need 3 birthday cards next month and 2 congratulatory cards, etc). When I initially thought of this idea, I had a line of questions. I will put them in future-based format and then turn them into the past:

The future

- Would you use a subscription box that allowed you to have curated stationary for all the events you need delivered right to your door?

- How often would you want the subscription box to come?

- Would order a curated stationary subscription box?

- On a scale of 1–10, how likely are you to order a curated stationary subscription box?

- How much would you pay for a curated stationary subscription box?

- Would you pay $15 a month for a curated stationary subscription box?

- What else would you like to receive in your curated stationary subscription box? Tea, cookies, cats?

Quite honestly, if I do say so myself, this curated stationary box sounds pretty wonderful. In all fairness, I would have answered yes to these questions, and paid the $15 a month. However, it is quite funny because, there are stationary subscription boxes out there already, and, I subscribe to none of them. On top of that, once this was out, I can’t say for certainty that I would subscribe. Hell, I can’t even say for sure what will happen tomorrow, so how can I predict something like this? (If you answered yes to any of the above questions, shoot me a line. Kidding.)

The past

How do we turn these into more helpful questions?

First, more general questions:

- Have you ever ordered a subscription box in the past? Why or why not?

- What type of box?

- How often did it arrive? What was your experience with that?

- How did you feel about the experience?

- What value did this subscription box bring?

- If you can remember, how much did you pay for the subscription box? What did you think of that price?

Second, dive more into the specifics:

- Have you ever ordered a stationary subscription box in the past? Why or why not?

- How was your experience with the box?

- How often did it arrive? What was your experience with that?

- Walk me through the last stationary subscription box you received and the contents in it.

- How much did you pay for the stationary subscription box? What did you think of the price?

- How much would you pay for a curated stationary subscription box?

- What was missing from the stationary subscription box?

So, that is how I would switch from the future to the past. This is, potentially, assuming someone has ordered these in the past and, you might be sitting there thinking “what if my participant hasn’t ordered subscription boxes in the past?” There are three things you can do:

- Screen your participants to ensure they have ordered them in the past

- Take the time to figure out why they haven’t ordered subscription boxes in the past, as that can be very useful information when deciding either to move forward or not, as well as how to move forward

- In this scenario, you could also ask about subscriptions in general, to understand what they subscribe to (such as Netflix, Amazon prime, etc), to better understand what might be missing from a subscription box

In addition to this, I have another simple method to help teams. Once the researcher conducts theses interviews, where the past is discussed and analyzed, don’t just jump straight into development and roll-out. Instead:

- Prototype the concept — put this idea into a prototype form, and see how people react. I have done this before and heard people say, “wow, I would never pay for that” or “oh, yeah, that makes sense as a premium feature.”

- Thereafter, A/B test the concept. Don’t just roll it out to all of your customers — test to see what happens: Is there a drop in retention? Or in conversion rate? Is no one interacting with the feature? Or the exact opposite?

With all these methods, there is really no reason to be asking future-based questions, and basing features or products solely around this shaky foundation. We want to build better products that improve people’s lives, so let’s use the best predictor to make sure we can accomplish that in the future!

A follow-up: growing the maturity of UX Research at your company

How to determine UX maturity and actionable steps forward

Have you ever thought about the quality and effectiveness of the user research (or UX) practice at your current company? Or where your company stands in terms of how you are currently using user research? Or, most importantly, what level you are on and how to get to the next level of user research?

I think about this all the time. Processes, frameworks and how I am currently running user research can sometimes keep me up at night. The other day, I decided it was time to actually put my questions and thoughts into a framework, which was when I was introduced to the concept of UX maturity and UX maturity models

What is UX Maturity?

UX maturity is as it sounds: it is, essentially, how mature your organization is when it comes to dealing with UX and user research practices. For the purpose of this article, I am going to focus specifically on user research. Fortunately for all of us, the area of UX maturity has been researched, and there have been some wonderful resources created in this space, such as UX maturity models.

A UX maturity model enables a company to do exactly what I mentioned above: assess how mature a company is with their user research.

For me, UX maturity models are a really helpful guide in understanding the purpose of user research in a company, whether it is non-existent, a tool to validate design decisions, a way to discover new insights, a method to innovate or a combination of the above (the good ones, usually).

A model like this gives you a clear framework, allowing you to actually understand where you currently lie on the UX maturity scale, and what you have to do in order to get to the next steps.

Generally, the more UX research mature a company is, the more likely that are to fight for including user research in their business.

What can assessing UX maturity do for you? Aka: why does it matter?

Assessing where your company currently lies within a UX maturity model is important for several reasons:

- Obtain a greater understanding about how much buy-in user research currently has in your organization

- You acquire action items for what you need to do as a user researcher to move the company in a more user-centric direction

- Helps gain buy-in by approaching user research in the most appropriate way for your organization

How to assess UX maturity

UX maturity models tend to have five or six different levels, depending on which you are looking at. Here are the most common hierarchies of UX research maturity:

- Absence/Unawareness of UX Research

The organization is basically unaware of user research, and the value of conducting research. There is an absence of processes and movement in user research - UX Research Awareness — Ad Hoc Research

There is an awareness of user research, but it is commonly misunderstood as a tool to validate changes, or to “make something look pretty.” Oftentimes, there will be ad hoc research requests that come very late in the pipeline - Adoption of UX research into projects

This is where UX research comes into projects earlier than in stage two, and starts to become part of whatever development cycle the team is using - Maturing of UX research into an organizational focus

User research becomes part of the organizational process, and has its own place in the organization. Teams and stakeholders are bought in, and ensure research is done, when necessary - Integrated UX research across strategy

Instead of simply informing minor aesthetic changes, or being used to validate changes, user research is able to inform product strategy, as well as other strategies across the organization (ex: marketing, brand, etc.) - Complete UX research culture

Where every user researcher wants their organization to be: the entire company is research-centric and driven by a need to understand users. UX is an integral part of the organization’s thinking process at every level

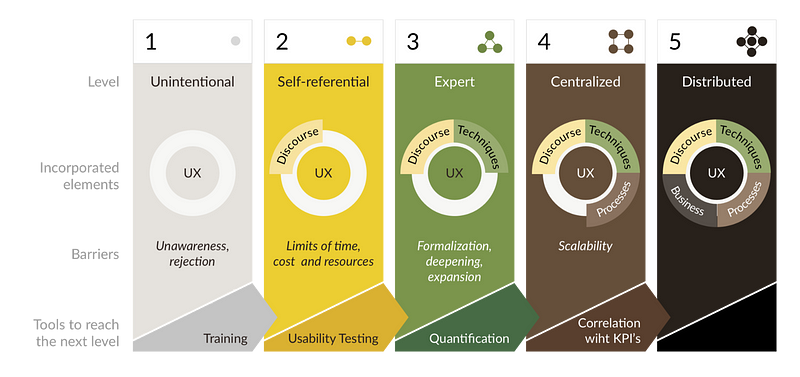

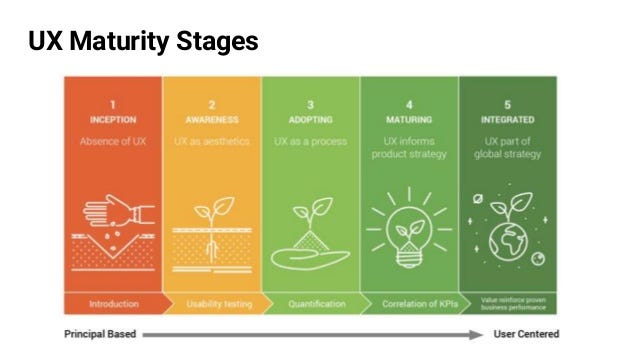

There are many models available to use, such as the one below, used by GetYourGuide. This model is a great way to get started in determining, at a high-level, where the UX maturity lies at your organization.

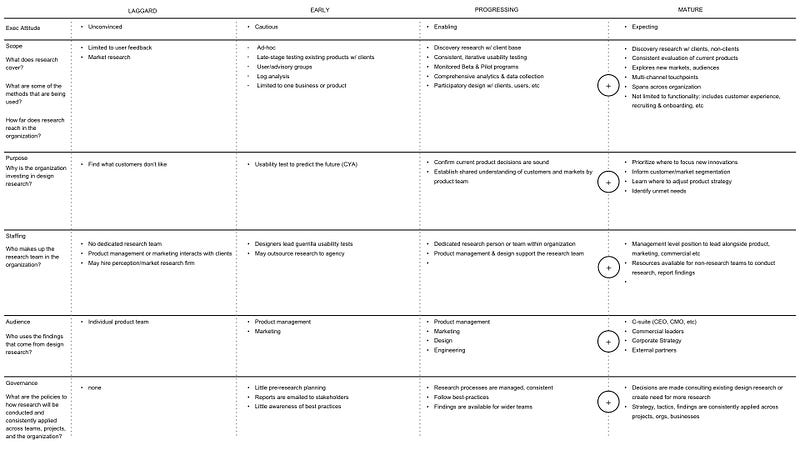

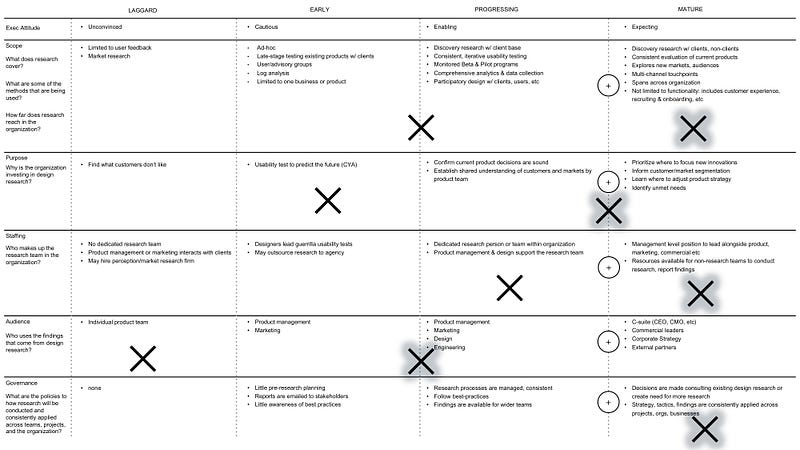

Once you get this overview of the UX maturity, you can dive in a little deeper, using this more detailed model by Nasdaq:

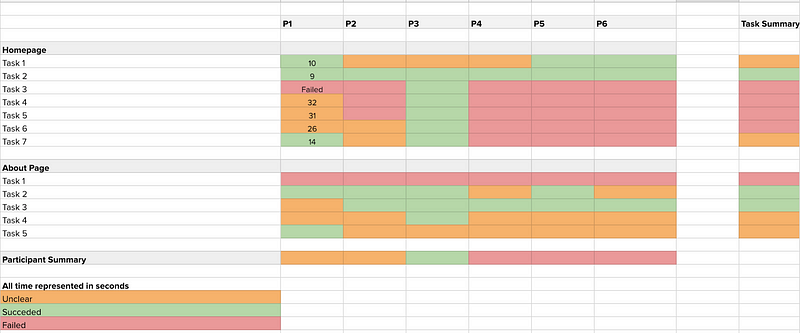

This particular maturity model can end up looking more like a bingo board, with some areas may be more mature than others, which is why I love this particular model, and have used it at the company I currently work for. I identified our overall maturity using the first model, but I knew Nasdaq’s model would work better for us, specifically, because we were further along in some areas than others. This is what it looked like when I was done:

After I went through and completed this model, I had very clear insight into what I had to do next:

- We had to move more into the direction of discovery research — I currently run generative research studies regularly, but there is a lot more work I need to do in terms of education, and how to work alongside our squads with this discovery research

- I want to start beta and pilot programs as soon as we have new concepts applicable for these types of methodologies

- We need to up our data collection and analytics game when it comes to user research metrics (such as time on task, task success). With this, I am currently working on a heuristic evaluation, and we are going to start recruitment for a benchmarking study

- As we have recently started discovery research, we still need to create outputs that foster shared understanding throughout the team, such as personas, user journeys, user scenarios, comic storyboard, etc

- I would really like to start making sure the research is integrated throughout all the different departments — as of right now, I am just trying to make sure each squad is introduced to the concept of research, and the finding we have so far. As time goes by, I will be holding more synthesis meetings and presentations that include other departments. This is a particular focus for me this coming quarter

- Finally, I would like to focus on creating more frameworks and processes across user research — right now, we have best practices and an overall idea of how we want user research to work, but I would like to ingrain research into the squads in a very obvious and easy-to-follow way

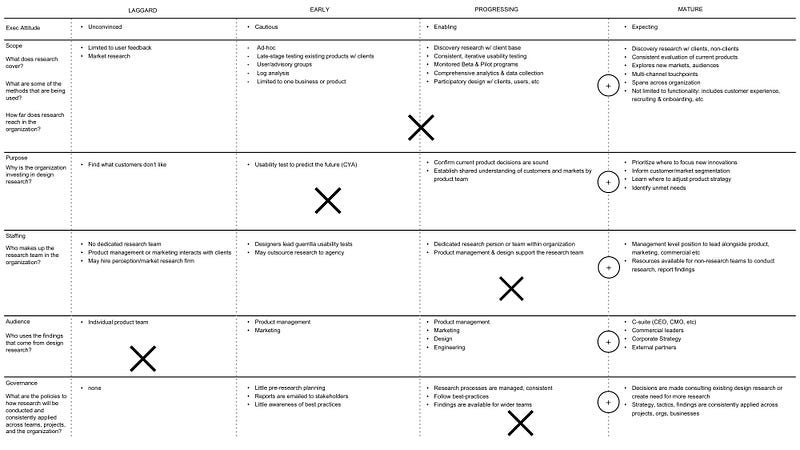

Although I already had an idea that this was the work I needed to do to help user research level up, it was certainly helpful to map out where we currently lie on a pre-defined model, where I could easily see what the next step would look like. With this, I made my plan for the upcoming year, which is a bit optimistic (the ones with the glow are where I would like to be):

As I am currently the sole researcher on the team, I am hoping to accomplish as much as I can with this model in the upcoming year, and will post an update of our new maturity then. I can’t say enough how helpful this simple exercise was, and I really encourage you to give it a try!

See the original post, based off of a recent ResearchOps Berlin Meetup

Being a good user researcher goes beyond empathy

15 traits and skills valuable to a user researcher.

I’m not going to lie, being a user researcher is a really cool job: I have a variety of different activities I could be tackling in a given week or day, I have the opportunity to make a long-lasting positive impact, I can talk to people to more deeply understand them (fascinating), I write research plans and I also get to run fun brainstorming workshops with cookies and pizza.

It’s super enjoyable, but, I have found, it does take a certain type of person to be a user researcher. While I have some natural tendencies towards the job, I have had to evolve some of my other qualities. For instance, I am very much introverted. On the surface, you might not be able to tell, but it is more about the fact that being around a bunch of people and listening intently can be quite draining for me. Because of this, I have had to balance how I approach work, such as:

- No more than three research sessions in one day

- Try to avoid moderating too many back-to-back workshops

- Attempt to make Monday and Tuesday my “meeting days” in order to have fewer team meetings throughout the week

- Take some days to work from home sometimes, in order to recharge (when I have a more meeting-free day and don’t have research sessions scheduled)

That being said, there are some more obvious qualities that a user researcher should tend towards (or work on). We all know empathy and friendliness are key, but what are the lesser known characteristics that benefit user researchers?

User research personality traits

- Perceptiveness

We need to take in everything that is going on around us, especially during research sessions. By being perceptive, we are able to filter out the noise, and hone in on the most important pieces of what participants are telling us. This trait allows us to ask crucial questions on the spot, instead of realizing the opportunity was missed later on - Open-mindedness and calmness

Looking for patterns in data, in order to deliver insights, is critical in making a successful user researcher, but it is extremely important to not jump to conclusions when synthesizing research. We need to remain calm and open to all possibilities, in order to see grey areas others may miss. This also applies to realizing we can’t understand or do everything perfectly - Neutrality

Frankly, we aren’t really meant to have opinions but, instead, are meant to share all the facts with others in the most unbiased way. During research, we don’t really respond to what participants are saying. There have been times I have wanted to laugh, cry and hang up the call, but it is our duty to listen, dispassionately to what others are saying…although, this doesn’t mean you act like a robot - People management

As a researcher, I interact with many people from product owners to designers, developers to marketing, finance/legal to branding. Sometimes there can be a good amount of chasing and babysitting, to ensure research gets done properly (and isn’t pulled in too late to a project). I create bi-weekly meetings with product owners and designers so that research isn’t left behind. I also created a one-pager on how to work with a user researcher - A whole lotta patience

Similar to above, with chasing and educating, there is a need for a degree of patience. User research isn’t concrete enough as a field to simply be known (or understood correctly). In addition, it can get boring sitting through hours of interviews with people who are telling you, seemingly, similar stories or taking the same actions on tasks. However, we need the patience to look through each interview with a lens of fascination and potential. Also, be patient with last minute cancellations! - Mental juggling

Specifically during research sessions, we do a lot of different things simultaneously: observing, listening, understanding, forming questions, time-keeping, empathizing, knowing when to dig deeper, managing observers, etc. This is a lot of stuff to do at once, so we need to have the mental capacity to juggle all of this competing information. I use meditation to help with focus and clearing my mind. That, and lots of practice! - Be compelling

Often, we need to convince others of the value of user research, as well as evangelizing the voice of the user. In order to do this, we need persuasion, but without the negative connotation that word usually entails. It is important to understand the fears or misconceptions of user research and then present research projects and findings in a way that quells those fears - Having a touch of romanticism

Researchers generally want to make the world a better place and to improve people’s lives. A degree of romanticism is necessary in allowing us to forge forward through common obstacles and struggles. At the end of the day, all we want to do is help others, both companies and users

User research skills

- Ability to collaborate

As mentioned above, researchers can touch many different departments and are often considered a “service” for teams to use. In this sense, we need to be able to collaborate with all different areas of a company, whether that be product, tech, marketing, finance, legal, etc. Making yourself as approachable as possible, and taking the time to understand someone’s previous experience with user research enables you the opportunity to collaborate even more - Adaptability and admittance

User research can be unexpected — a connection could be lost, a participant could be hard to handle, a method may not be working well, someone could question and dissolve your research findings through something you didn’t know. We have to be flexible in changing methods and working with what is directly in front of us in any given moment. I now expect the unexpected and am happy to admit I did something wrong or that I simply don’t know - Teaching

One of the best things I have done at every company or consultant position I held was to teach others how to perform basic user research (primarily usability tests). Being able to explain concepts to people in a way that enables them to understand not only helps you educate people in an area with many misunderstandings, but can also come in handy for facilitating brainstorming sessions or fielding the many questions a user researcher gets asked when presenting findings (ONLY 10 PEOPLE?!) - Learning quickly

Especially in the freelance/consultancy world, we need to learn quickly: learn about the people we are working with, how teams are structured, the processes we need research to fit into, the domain we are a part of, different types of technology, new research methods. We don’t need to become experts in everything, but it is important to be able to recognize commonalities between what you know and things you are trying to learn, as well as putting in the time to properly absorb information necessary to your performance - Have a good memory

This might seem obvious, extremely helpful. This is key when moderating interviews, as you can memorize the script you need, making the session much more natural for you and the participant. There is a lot of information to be stored, and you are bound to forget some details, but having a good memory enables you to make connections between research participants (and even projects) that others might miss - Writing

I write a lot in my day-to-day activities, such as recruitment emails, scheduling emails, presentations, research summaries, personas, scenarios, one-pagers, budgets, research plans, screeners, surveys…the list goes on. Sometimes, I even help with UX copywriting for my designers (we don’t have that role filled yet). Being a structured, concise yet friendly writer can really aid you, and save you time with editing - Storytelling

And, of course, storytelling…what does that even me? To me, I care about people’s stories because I think they are an integral part of understanding someone and then communicating research to others. In order to effectively get others to understand our users, and the impact our product has on them, I need to string together the stories users tell me in order to convey meaning. If you are interested in more, I talk about storytelling for a research portfolio here

Don’t have these skills or traits?

That is okay, and doesn’t mean you can’t be a user researcher, or try it out. I have just realized these are very helpful qualities and abilities to have. If you fall short on some of these, they can definitely be learned and sharpened over time. Not all of us are perfect and, as a researcher, of course I talk about the ideal. We all have our own strengths, and areas of improvement. As with anything in user research, it just takes practice!

UX Maturity: How to Grow User Research in your Organization

Our second ResearchOps Berlin Meetup, hosted by FlixBus, was an insightful presentation on how to assess your organization’s level of maturity, and how to help your organization foster and grow a user research practice. We then followed-up with group discussions on the challenges we face in organizations, when they are not quite as “UX research mature” as we could hope.

****

On April 8th, we were fortunate enough to hold our second ResearchOps Berlin meeting. FlixBus was our wonderful host, and also delivered an actionable presentation on how they have managed to foster and grow user research at FlixBus. We found this talk to be extremely inspiring as many user researchers face this very challenge: how do we best approach growing our user research practice at an organization? The follow-up discussion made it very clear that there are patterns in the problems we all face.

Luky, Pietro and Carolina took the time to bring us through the story about the maturation of user research at FlixBus. It all started when Luky, previously a UX designer, was asked by colleagues to make a pop-up look nice. For all UX’ers reading this, I know you may have just cringed. Luky quickly realized her colleagues were completely focused on the solution, as opposed to the problem: pop-ups are annoying! This was two years ago: there was no dedicated UX researcher or research processes, and decisions were made based on a gut feeling. They decided things had to change.

UX Maturity Models

After understanding the need for user research at FlixBus, the team decided to use a UX Maturity model in order to assess the current state of user research, and how to get to the next levels.

What is UX Maturity?

How do we know what stage an organization is in with understanding and implementing user research techniques and processes? This is where UX Maturity models come into play. They are a framework that enable organizations to categorize the quality and effectiveness of their user research processes and practice. Generally, the more UX research mature a company is, the more likely that are to fight for including user research in their business.

How do we assess maturity?

During the presentation, the FlixBus team gave us a peak into how they define and assess UX maturity through a maturity model adapted from GetYourGuide to help us visualize the different steps.

Most maturity models, one of the most famous is from Nasdaq, have a similar pattern consisting of five or six levels of UX maturity, the lowest in which UX is absent, the highest in which the organization has developed a research-centric culture. As organizations mature, they are better equipped, and more likely, to make use of user research, and incorporate it into business strategy.

- Absence/Unawareness of UX Research

The organization is basically unaware of user research, and the value of conducting research. There is an absence of processes and movement in user research - UX Research Awareness — Ad Hoc Research

There is an awareness of user research, but it is commonly misunderstood as a tool to validate changes, or to “make something look pretty.” Oftentimes, there will be ad hoc research requests that come very late in the pipeline - Adoption of UX research into projects

This is where UX research comes into projects earlier than in stage two, and starts to become part of whatever development cycle the team is using - Maturing of UX research into an organizational focus

User research becomes part of the organizational process, and has its own place in the organization. Teams and stakeholders are bought in, and ensure research is done, when necessary - Integrated UX research across strategy

Instead of simply informing minor aesthetic changes, or being used to validate changes, user research is able to inform product strategy, as well as other strategies across the organization (ex: marketing, brand, etc.) - Complete UX research culture

Where every user researcher wants their organization to be: the entire company is research-centric and driven by a need to understand users. UX is an integral part of the organization’s thinking process at every level

How to mature?

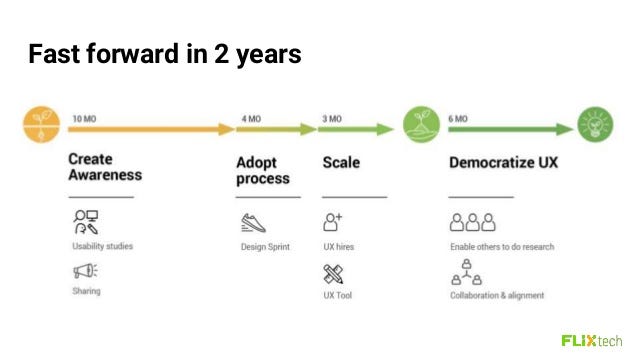

In addition to the UX maturity model, the FlixBus team shared how, exactly, they have been able to increase the UX research maturity over the past few years. They explained some tips and tricks all of us can employ in our organizations.

In order to create awareness of user research, they started with a few different methods. These internal methods, such as testing with employees, allowed them to feel more comfortable and confident when speaking with customers. It also allowed them to gather some buy-in and excitement around user research before jumping right into research interview sessions.

- Unmoderated remote studies with employees

- Moderated onsite studies with employees

- Moderated onsite studies with customers

Once they completed these usability tests, the team needed to understand how to best share user research across FlixBus. They created strategies on how to best share the research to the company, which allowed them to level-up in terms of maturity and getting the organization to be more aware of user research and the value it provides to the company.

- Attended meet-ups and conferences in order to get to know other researchers, and understand how other organizations incorporate user research.

- Held internal knowledge sharing and user research workshops, in order to, both, educate and share the findings from their research sessions.

- Created a blogpost on how testing with employees can be a great starting point to incorporating user research into your organization.

- Shared a UX research findings template, so others could easily do research and share their findings to the organization.

- Showed videos of usability sessions to create a shared understanding of where customers tended to struggle.

- Produced an affinity map with the research findings from the various studies, in order to make the results easier to synthesize and digest. This also gave them actionable next steps forward on how to implement the user research findings.

- Incorporated design sprints to include user research into the overall process.

Luckily, at FlixBus, with these methods, the demand for user research continues to increase!

Scaling user research and maturity

The FlixBus team found themselves in a position, I believe, all user researchers find cause for celebration: people learned about user research, found the value and were excited to conduct more! In this case, the team had to figure out how to scale user research in order to handle all the incoming research requests.

- Using the right tools, such as a remote testing tool that allows for mixed-methods (FlixBus uses Usertesting.com)

- Hiring more UX people, such as researchers

- Aligning with Product Owners to understand their roadmap, and properly prioritize research projects

- Continuing to share findings to generate discussions on slack channels

- Training other employees (product owners, designers, developers, etc.) to do user research

- Testing problems instead of solutions

- Using methodologies at higher maturity levels, such as field studies and guerrilla research or UX Croissant: where they test new features/ideas internally with employees in a speed-dating style user lab

We finished the meetup with a great group discuss on all the different areas we struggle in, when it comes to leveling up UX research maturity. Some of the most common problems were:

- How to get continuous buy-in from stakeholders

- How to make researchers feel valuable so they don’t leave the organization

- How to hire UX researchers (especially those who will be working solo)

- How to get feedback on a product concept/idea that is not currently in development (or live)

Overall, we all struggle with similar issues, and FlixBus was able to give us some actionable tips of how to, first, assess UX research maturity, and how to (slowly) get to the next level.

If you are interested in more in-depth information, we recommend checking out the presentation on SlideShare and also the video on Youtube. Also, keep checking our ResearchOps Berlin Meetup page for our next events!

I’m Writing for dscout!

But I’m not leaving anyone behind

Hey, everyone, I have a cool announcement that I hope you will celebrate with me.

I was contacted by dscout a few months ago to create some content for them on their blog, People Nerds. Here are a few reasons this was exciting for me:

- Since I was about 5 years old, I have dreamed about being a writer, so, having someone approach me about writing for them was a real dream come true

- It forces me to create high-quality content on a regular basis — not that I don’t want to do this, but it is really nice to have a schedule

- The people at dscout are really cool, and I actually believe in their vision, as well as their product

That being said, this doesn’t really impact my writing on Medium in the sense that I will still be creating separate content for you all, as often as I can. However, I do recommend you also check out my content on dscout (and their content in general), because it is aligned with the type of information I post here.

My recent dscout postings:

How to Ace the Dreaded Whiteboard Challenge

Yes, the whiteboard challenge can be a dreaded and anxiety-ridden experience, but you can also turn it into a fun, enlightening exercise.

17 Tips the Pros Use to Master One-on-One Interviews

In a nutshell, what I have learned is: User research is a bit like improv. Here are a few ways you can nail the performance.

9 Research and Productivity Hacks for UX/UR Teams of One

On a small research team with big ideas? Learn how to prioritize the big-picture goals while juggling the day-to-day challenges — all in a day’s work.

I will be writing two articles a month for dscout, so feel free to follow me on there as well, if you would like. I hope you all understand this small shift, and please let me know if you have any feedback or questions on this.

Getting GDPR compliant

How an American user researcher met GDPR.

I’m originally from America. All obvious jokes ignorant American jokes aside, I never really understood the whole concept around data privacy and GDPR. My entire user research career was based in the United States, and, through my limited scope of knowledge in the topic, it didn’t really affect me. I had my lean, but informative consent forms, knew to ask permission to record sessions and anonymized participants. I was fine.

Until I moved to Europe, specifically Germany. There I was, in this new role in a new country, excited to get started with user research. I was armed with my American consent form and recruitment tactics. Since the role was Senior Researcher, and it was a start-up, I was ready to just move forward on my own with everything I had learned up until that moment.

I knew GDPR was important in the EU, but I didn’t take the time to really familiarize myself with how it might impact my day-to-day role. I played the role of ignorant American pretty well. But, really, I promise it was well-intentioned.

Why did I start caring about GDPR

Other than moving to Germany, where GDPR is much more apparent, one particular event occurred to knock me over the head with how important it is understand these concepts:

I made a mistake when recruiting from a list of our participants. Instead of BCC’ing a group of customers, I CC’d them. Luckily, it was a small list of people, to which I immediately apologized. We then contacted our data privacy officer to understand what the next steps were. For those few days, I was terrified I would lose my job and be shamed by the GDPR gods, but am happy to share the experience with others. Don’t mass email customers, even if you have no other tool and are excited to get research underway (duh).

Fortunately, the whole thing was considered extremely minor, and was reported to the necessary people, and it all blew over in a few days. But, that event taught me a lot: to take GDPR and data privacy more seriously than I had in my previous roles.

Maybe you all aren’t like me, and actually took the time to read more about GDPR, but, even those articles are lengthy and, for me, didn’t break GDPR down into actions I had to take, which is why I am writing this article. I am not going to cover everything regarding GDPR, but, instead, some actions I put into practice recently, even if, retrospectively, they seem like common sense.

How I have handled GDPR & data privacy moving forward

Once I realized how important GDPR would be for me to conduct user research in the EU, I decided to take action in better understanding and adhering to GDPR. It isn’t like it’s going anywhere, might as well become friends.

Talk to your legal team

I immediately contacted our legal team to get more advice. I sent them an updated consent form, as well as my recruiting screener to review. Note: this takes a very long time, and I wish I had done it right when I started at the company, but, lesson learned. Since then, we have been going back and forth on how to “GDPR-ize” the user research process.

Recruiting

Not going to lie, GDPR has definitely killed my fun recruiting vibes. I quickly learned I couldn’t simply recruit anyone who hadn’t explicitly signed up for our newsletter (already given consent to receiving communication with us), which limited the scope of participants I could choose from. I also realized some of the data from the recruitment survey was not recommended, and the approach of, let’s get as much as we can and use what we need, would not fly here. This is what I have done:

- Trimmed my recruitment survey down to the bare bones of what I need to contact the participants, with very few questions on demographics. This survey also provides participants the option to skip or not answer any question (even required ones), and links to our data privacy policy

- Agreed to delete the recruitment data after one week to ensure the utter anonymity of our participants, and that their research sessions could not be linked to any personal data

- I have only been recruiting from our newsletter subscription list, as I know that is the “safe route.” I am hoping to open up recruiting through different means, such as a HotJar integration. If anyone else has any GDPR-compliant ways of recruiting, I would love to hear. I know we have to be careful with incentivizing!

Consent Forms

With consent forms, I often thought less was more, albeit that being very un-American. I was wrong. My one-pager, double signature consent form was simply not sufficient. I went back-and-forth with legal on how to make our consent form GDPR-compliant. There are a lot of examples out there, but not one that necessarily took the cake.

I created a template for you all, including a consent form (double signature) and a data privacy agreement. It is pretty standard, but I figure, sharing is caring.

Data Processing Agreements

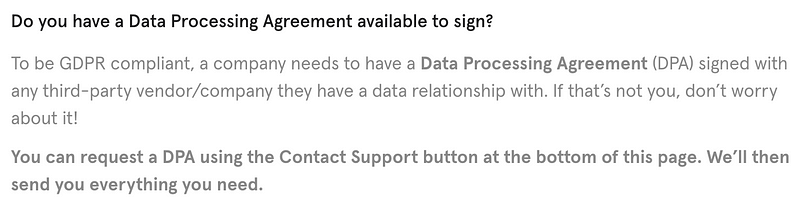

Whew, I had no idea what a DPA was before I started exploring this wonderful land of GDPR. We use Typeform as a recruitment tool because, well, Typeform is beautiful and easy to use. Little did I know, we couldn’t simply use Typeform, although they are GDPR compliant. We had to actually enter a data processing agreement with them. We are in the process of doing this…note: it takes time on legal’s side. However, Typeform made this extremely easy:

In addition to Typeform, we use Google Drive to store research sessions. Now, Google doesn’t do it in the same way as Typeform. Instead, you have to ‘opt-in’ to Google’s terms.

Now we are exploring what all of this means with legal, in order to make sure we are covered.

Storing research

This is actually my biggest pain point, even more so than recruitment. In terms of storing research, such as recordings, GDPR and data privacy guidelines ask that you store it only for the amount of time it is necessary. Now, in my opinion, the amount of time a company may find research sessions necessary and helpful could be…well, forever. In terms of usability tests, sure, I could see deleting those after a few months, or when the changes have been made, but, generative research. *Sigh*. I just can’t see a world in which research gets erased, so I am still struggling with this.

My biggest takeaways

- Take this seriously, and don’t try to get away with not dealing with these annoying rules

- Understand, at least, the basics of GDPR and how to implement GDPR-compliant research practices

- Talk to legal as soon as possible to start these conversations, as it can take a lot of time to get everything together. Right now, I am still blocked

- Accept the fact that you might not have taken the time to understand something so important :)

How have you incorporated GDPR into your research practice? I would love to hear more.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Elevate your research objectives

Write better research objectives to get better insights

I remember the first time I wrote a research plan. It took me hours (days, if I am being honest), and I was still pretty unclear as to why I had to write one. Ever since moving from academic research, I made any attempt to avoid processes, as they made up the bulk of research I did during my MA program. However, after some time, I came to learn how utterly important research plans are, as the contain the very material that drives and gives structure to your research sessions.

How do I write objectives?

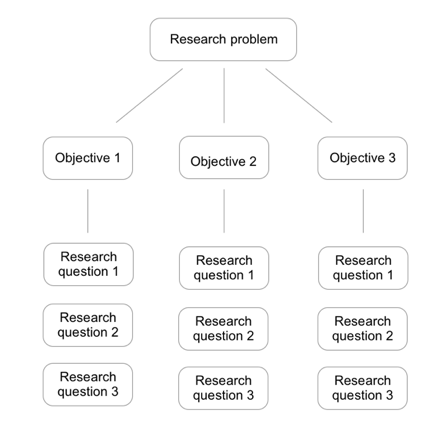

Objectives boil down to the main reasons you are doing the research; they are the specific ideas you want to learn more about during the research and the questions you want answered during the research. Essentially, the objectives drive the entire project, since they are the questions we want answered.

First, you have to start with a research problem statement. This is the central question that has to be answered by the research findings. The problem statement is WHAT we will be studying, and is the overarching topic your research project is about.

Example topic: To assess how people make travel decisions

Once we create this problem statement, we can start writing our objectives.

Our research objectives should address HOW we are going to study the problem statement. We do this by breaking the research problem down into several objectives. Here are the steps I bring myself through, and then talk through the steps using the travel example from above:

- I ask myself: “what am I trying to learn?” and “what must the research achieve?”

- Identify what stage of the idea is being researched (prototype, concept, etc)

- Talk to your team to align with what they want to learn

What am I trying to learn

I want to understand how people make travel decisions in order to, ultimately, improve that decision-making process.

However, this statement is broad, and we need to break it down to what we want to learn about that problem statement. To do this, I sit at a whiteboard and brainstorm all the different areas I am interested in, or the different assumptions I have. I want to learn:

- How people currently make travel decisions

- Why they decide to travel; who else is involved; when do they travel; where do they travel to; how do they travel

- What tools people use to make travel decisions

- How they feel about the current decision-making process

- What problems they encounter when trying to make travel decisions

- What improvements they would make to their current decision-making process

Once I dismantle the problem statement, I feel more comfortable forming objectives.

What is being researched

Knowing what exactly we are researching will also help us hone into our research objectives. I am constantly researching the following:

- A concept or idea: we need to understand the process people are currently going through (generative research)

- A prototype: we need to uncover what people think about the prototype and how they expect to use it (generative + usability testing)

- Live code: we need to evaluate the performance of the product and what people think about it (usability testing)

These will change your objectives slightly to know whether you are focused on understanding an overall concept/idea, uncovering what people expect from a product or evaluating the performance of a product. A usability test is far different from generative research, so it is important to know what type of research we are doing, as it helps us understand what we can expect to learn.

Talk to your team

I talk to all my (three, soon to be four) teams very often and we tend to form the problem statement together, in order to ensure we are aligned on the overarching idea for the project. Once we have the idea, I set some objectives and approach the team to ask them:

- What they want to learn from the research project

- What are they expecting from the research

This way, you clarify whether or not you are missing out on a perspective or angle in your objectives. Once I have all this information, I form the objectives. For this example, I am trying to understand a concept through generative research. So my objectives will be focused on understanding people’s current processes:

Sample objectives

- Understand the end-to-end process of how participants are currently making travel decisions

- Uncover the different tools participants use to make travel decisions

- Identify any problems or barriers they encounter when trying to make travel decisions

- Learn about any improvements participants might make to their current decision-making process

The research findings should ultimately be able to answer the problem statement: understanding how people make travel decisions, and it should be able to answer all of the objectives I am curious to learn more about. By building these objectives, I can ensure I ask the right types of the questions, and I create a path in which I can guide participants down.

Travel is a broad topic, and we could go in many different directions. These objectives narrow the scope, while still allowing for natural conversation and innovation.

Bad versus better objectives:

Here are some additional examples I have generated in order to exemplify good versus bad objectives.

Bad: Understand why participants travel

Better: Understand the end-to-end journey of how and why participants choose to travel

Why: The bad objective, “understand why participants travel” is still too broad, and feels more like a problem statement. With that objective, we don’t really have a direction, or boundaries.

Bad: Find out how to get participants to buy flight insurance

Better: Uncover participants’ thought processes and prior experiences behind flight insurance

Why: We don’t want to find out how to get someone to do something, because, how would we ask good questions to get that information? We are more interested in seeing what their thought process is behind flight insurance, and if/why they have used it in the past

Bad: Find out why people use Expedia to book travel

Better: Discover the different tools participants use when deciding to travel, and how they feel about each tool

Why: This could be helpful if Expedia is a tool your users frequently use instead of your platform. However, I have always found it better to first ask, in general, what kind of other tools are used, so you are not so hyper-focused and miss other opportunities to explore.

Great, I have objectives — now what?

Research objectives frame generative research questions. Your questions should be able to give you insights that answer your objectives. So when you ask a participant a question, it is ultimately answering one of the objectives. Turn each objective into 3–5 questions

For example:

Research problem: Understand how people make travel decisions

Objective 1: Understand the end-to-end process of how participants are currently making travel decisions

- Question 1: Think about the last time you traveled, walk me through your decision-making process

- Question 2: Explain how you felt during that process

- Question 3: Talk to me about what other factors influenced your decision

Objective 2: Identify any problems or barriers they encounter when trying to make travel decisions

- Question 1: Describe the last time you had a problem when making travel decisions

- Question 2: Were you able to solve the problem? What did you do to try to solve the problem?

- Question 3: How would you improve or change the situation?

Objective 3: Uncover the different tools participants use to make travel decisions

- Question 1: Talk me through the different tools you used while making this decision

- Question 2: Describe your experience with these different tools

- Question 3: Compare the different experiences you had with the tools OR talk about any tools you’ve heard of and haven’t used

By starting off with a project with strong research objectives, you are far more likely to get impactful, actionable and deep insights that will help inform the company what the best next steps are. Since I have started really paying attention to, and honing, my research objectives, my interviews have visibly improved and my confidence in interviewing has greatly increased. Besides that, it is a fun exercise to deconstruct a problem statement into smaller puzzle pieces that move you toward your goal!

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Have a ‘difficult’ participant? Turn the beat around

How to deal with interesting participant personalities

While I shy away from calling anyone a “bad” participant, I do know, as user researchers, we can come up against some pretty difficult and interesting participant personalities. This can make for really unfruitful conversations. When we only have time and budget to talk to a smaller amount of users, we want the conversations to be as rich and productive as possible. Although we can sometimes become accustomed to playing the role of a psychologist, babysitter, flight attendant and juggler, there is no reason we can’t try to turn these situations around.

Working with a variety of participant types is part of a researchers job. As we go through these experiences, we get better at handling each, unique situation, and are more adept at staying open-minded in the face of adversity. This is a skill you can only learn by encountering these scenarios.

What are some of these personalities?

There are many participant personalities floating around, but I wanted to list out the common ones my colleagues and I have seen. If I had the design skills, I would love to make them into personas, but, alas, I am merely a researcher.

- Vicious Venter. This person agreed to the research session, not to help, but to make sure you know he/she hates your product, and all the ways your product has messed up his/her life.

- The Blank Stare. Every time you ask a question, you receive a confused look. This participant speaks very little and is, seemingly, unsure about how to use technology.

- Distractions Everywhere. Bing, bong, boop. Any distraction available will take the attention away from the interview.

- No Opinions. No researcher likes to hear the words, “it’s fine” or “it’s pretty good.” When you dig, you hit a cement wall. It is almost as if there are no emotions present.

- The Perfectionist. One of the most difficult participants for a usability test, since they really want to make sure they are doing everything perfectly. They will often ask you more questions than you ask them.

- Tech-Savvy Solutionist. They could have built a better app, and they will tell you how.

- Your New BFF. Because of social desirability bias, some participants may try to befriend you or make sure everything they say is kind or flattering. Almost the opposite of the vicious venter.

- The Self-Blamer. They will blame themselves for the problems they encounter, instead of the system, and may get easily frustrated.

- The Rambler. Will often go off-topic and speak about irrelevant information, making the sessions unproductive.

Tips on tough participants

Yes, we have seen these personalities come up, but what can we actually do in these scenarios?

First off, take a deep breath. Normally, when you have a difficult participant, it could actually be your fault. For instance, the time wasn’t taken to make the participant comfortable, or they feel like you aren’t listening. It is important to go through a checklist to ensure you did everything on your side to make the research session as enjoyable as possible.

- Vicious Venter. We don’t want to interrupt the venter, because that generally doesn’t help the situation, so we have to find ways around this. I try to divert the conversation by saying, “I understand what you are saying, and I want to get back to that later on, but I would like to focus on this…” Another option is actually trying to listen by going on the journey with the venter, and using some quotes for insight.

- The Blank Stare. It can get frustrating when participants are very unsure about how to use technology, but try your best to resist the urge to immediately help the participant. Let him/her struggle through the process for a little, take note of it and then intervene so you don’t spend the entire session watching the participant on one task.

- Distractions Everywhere. Ensure there are as few distractions in the room as possible, such as cell phones, computers, even clocks. Additionally, try to make the environment as quiet as possible, with few people walking by the room. I often ask the participant to turn their phone on silent and place it away for the entire session.

- No Opinions. Make sure you ask open-ended questions as often as possible, as it makes it more difficult for participants to answer with lackluster statements. And, if they do, dig. If something is “fine” or “okay,” ask them why. Ask, what is “okay” or “fine” about it or what do they mean when they say “fine?” I will also ask, “how would you describe this to someone who has never seen it?”

- The Perfectionist. Whenever a participant asks me a question, such as a perfectionist asking, “is that right?” I turn the question right back to them, “what do you think?” Stress that there are no right or wrong answers in these situations, and you are just interested in their honest opinions.

- Tech-Savvy Solutionist. It is very easy to focus on solutions when you have a tech-forward participant, especially one who wants to tell you how to do things better. Always remember to focus on the problem. Yes, they may want all of these features, but why, what problem are they trying to solve or goal they are trying to achieve.

- Your New BFF. Stress how important honest feedback is. When faced with social desirability bias, it can be difficult for people to give critical feedback. Always encourage this type of information. To help, I mention no one in the room designed what they are giving feedback on, and that there will be no hurt feelings.

- The Self-Blamer. Remind this participant there are no right or wrong answers, and that usability tests are, in fact, not tests. During usability testing, I will refer to tasks as activities, as this takes the pressure off. Additionally, I will reassure a flustered participant that other participants had similar problems (which I tend not to do as this can introduce bias), so they may feel more at ease when encountering problems.

- The Rambler. It is exciting to find a person who wants to share a lot, but, oftentimes, ramblers can be off-topic, which can lead to very unproductive conversations. Similar to the venter, it is important to always try to steer the conversation back to the relevant topic, by using segues such as, “that is really interesting, and I want to circle back, but for the interest of time, could we focus on…” And just doing this over and over again to try and get as many useful insights as possible.

Overall tips for avoiding these situations

- Recruiting. Really think about your recruiting strategy. If you find you are getting participants that aren’t the best fit, take a look at how you are screening participants. Are you sure you are asking for the right criteria?

- Seize the moment. Even if you do everything right during your recruiting, some less than ideal participants can still slip through the cracks. In addition to the above techniques, it is important to use these situations to your advantage. Even though it may not be the best interview you have ever conducted, you can still get something out of it. Don’t just give up, use it as an experience to learn!

Do you have any experiences with the above? Or something different? I’d love to hear about any of your stories with different participants, and how you mitigate these different personalities or scenarios.

As a note: I don’t really think there are “bad” participants — there are some that are less ideal for certain projects, but none of them are downright awful. They serve as great learning experiences on how to improve our perspectives and practice.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

ACV laddering in user research

A simple method to uncover user’s core values.

Have you ever been in an interview where you feel you are so close to uncovering something crucial about the user’s behavior or motivation? For me, it happens quite often. I know there are shallow ways to respond to user research questions, and most participants respond in that way. Sometimes I do it myself when my students are interviewing me, simply because, it takes an awful lot of self-awareness to truly answer a question with a deep-rooted motivation. This is especially the case when you are sitting in front of a total stranger and they ask you to talk to them about how you use a product.

The above is the exact reason why we have widely known methods such as TEDW* or the 5-why’s techniques*. These methods get the user to open up and elaborate on their answers by focusing on open-ended questions, memory recall and stories. With these approaches, you can get much more emotional and rich qualitative data, including more deep insights into the participant’s mind.

The best thing a participant can do is tell us a story — we get all the context from someone who engaged in activity naturally, and we also get their retrospective opinion on the past. Although recalled memories can be “false,” we care most about their perception.

We have these tried and true methods, yes, but sometimes it simply doesn’t feel like enough. I can open up the conversation with all the TEDW questions in the world, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I will get to the core of a participant’s thought process or behavior. How do I get the most out of my (short) time with participants?

Enter the ACV ladder.

Where did ACV laddering come from?

Laddering was first introduced in the 1960s by, who other than, clinical psychologists. It was presented as a way to get through all of the noise in order to understand a person’s true values and belief system. It became so popular because it is a simple method of establishing a person’s mental models, and it is a well-established tool in the field of psychology. Yes, we aren’t psychologists but…

Being a user researcher sometimes feels like I am simultaneously trying to be a therapist

This methodology didn’t just pop out of nowhere, but is based on the means-end-chain theory. Since I don’t want to bore you with a long discussion on this (although I am totally a nerd and obsessed with this stuff), I will succinctly summarize:

The means-end-chain theory assigns a heirarchy to how people think about purchasing (because everything comes back to money):

- People look at the characteristics of a product (shiny, red car)

- People determine the functional, social and mental benefits for buying the product (I can get from point A to point B, I get a new car, the car is cool)

- People have unconscious thoughts about values that align with their reasoning for the purchase (A new car makes me feel cool, which makes me feel young, which, ultimately, makes me feel important and less insecure about my age, looks, etc.)

I know I mention only in the last point that thoughts are unconscious, but they tend to be fairly unconscious throughout the entire process.

Anyways…

So, what is ACV laddering?

Essentially, it is a type of probing that gets to a core value. ACV laddering breaks down the means-end-chain theory into three categories:

- Attributes (A) — The characteristics a person assigns to a product or a system

- Consequences © —Each attribute has a consequence, or gives the user a certain benefit and feeling associated with the product

- Core values (V) — Each consequence is linked to a value or belief system of that person, which is the unconscious (and hard to measure) driver of their behaviors

How do I use ACV laddering?

When we start to understand the different areas of the ACV ladder, we can identify where a participant is when they are responding, and try to urge them forward towards core values. For example:

- Q: Why do you like wine coolers? (Assuming the participant has indicated they do like them)

- A: They are less alcoholic than other options (attribute)

- Q: Interesting. Why do you like them because they are less alcoholic?

- A: I can’t drink as many as other types of alcohol, which is important (attribute)

- Q: Why is that important to you?

- A: I don’t get as drunk and tired (consequence)

- Q: And how does not getting as drunk and tired impact you?

- A: Well, I don’t want to look like a drunk…it is important for me to appear sophisticated (consequence)

- Q: Sophisticated?

- A: It is important for me to get the respect of others, and it is hard to do that when you’re drunk (core value)

With ACV laddering in mind, it is easier to pick up on attributes and consequences to, ultimately, get to someone’s core value behind their actions or thoughts. This also helps you get the most from your participants!

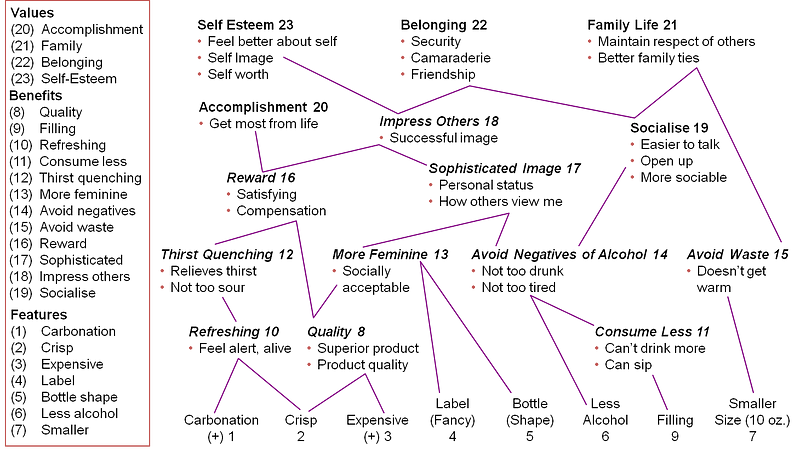

This information can then be used to create a hierarchical value map, which displays the ladder with the participant’s responses into a very visually stimulating map.

When you use ACV laddering, you get very concrete insights that are much deeper than whether or not someone liked something, or even a story they recall. This can really impact the user experience of a product, from how it is displayed, how the copy is written, how it is sold, the micro-interactions within a product, the colors and the even the order of screens shown to a user. Essentially, it can have a huge, company-wide impact.

I am using laddering to level-up as a user researcher and bring my team (and beyond) even better insights. What do you think?

*

The TEDW approach uses the following words to open up conversation, as opposed to asking yes/no or closed questions:

- “Talk me through/tell me about the last time you…”

- “Explain the last time/explain why…”

- “Describe what you were feeling/what happened…”

- “Walk me through how you…”

The 5-why’s technique is to remind us to ask why five times, in order to get to the core of why a participant is saying what he/she is saying

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Introducing doubt into User Research

Are we allowed to be wrong and iterate?

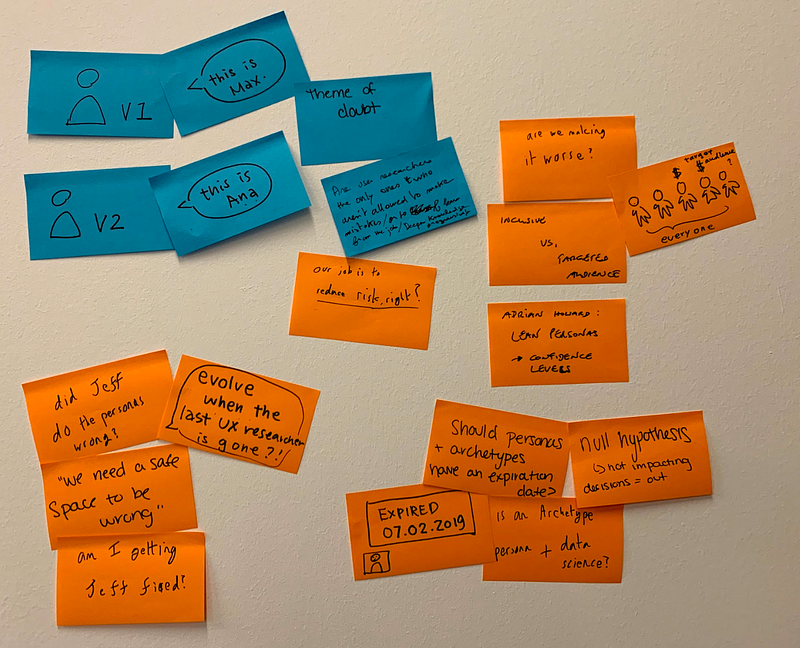

I recently co-organized a user research meetup here in Berlin (check us out, if you are interested). The topic was on personas and archetypes — fascinating and intriguing. We started with a talk by Smava, and then proceeded to split up the room into several groups to further discuss certain questions pertaining the topic. I was moderating one of the groups. Our question was:

How do we continuously evolve personas/archetypes, and continue to make them actionable for our teams?

Heavy question, but, I must admit, I was psyched to discuss this with my group. The conversation ended up going in a way I could have never imagined, and it still crosses my mind weeks later.

Our themes

We had about thirty minutes to discuss the above question, and none of us had ever met each other before. We had no idea where we came from or what experience any of us had with personas. So, we did what any other researchers would do: we went straight to the sticky notes.

While we started the discussion on evolving prototypes and making them actionable, the conversation started to evolve towards different themes/questions:

- Can we doubt user research?

- Should personas/archetypes have expiration dates?

- How do we set up personas/archetypes so we can evolve them?

I wish I had a transcription of the conversation, since it was filled with fascinating twists and turns, as well as common anecdotes of the challenges we face as user researchers.

I am going to tackle each theme, in reverse order, since, I think, they all can be held under the umbrella of doubt.

How do we set up personas/archetypes so they can evolve?

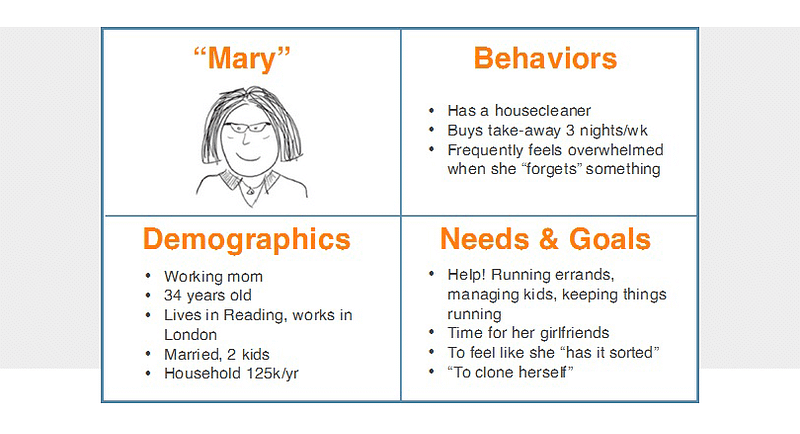

The concept of lean personas (or proto-personas) is an extremely popular concept. These types of personas are something I have used in previous companies, but they always led to a more finalized, and dare I say, “pretty” persona that ended up being more or less static.

Adrian Howard came up with the concept of the lean persona, which is, essentially, a more skeletal wireframe of a persona. There is less information, more concise formatting and it is definitely less visually aesthetic. Lean personas are great for startups or when there aren’t many resources available to create “real personas” (I kind of want to call them fat personas, but I digress).

However, lean personas can also be used to create sense of dynamism — the persona isn’t pretty or concrete enough to be static, instead, it can be shaped and iterated on. It can evolve with the research, the product and the team. People can write on it, cross things off. You don’t need to be a designer to edit a lean persona.

Expiration dates on user research outputs

I’m using the word output here for a specific reason: when I say output, it means things like personas, customer journey maps, and different visual representations of user research, not the outcomes of research.

Have you ever joined a company (or even been there for a bit) and asked, “where are the personas (or any other output)?” only to be met with a scrunched up face and the response, “ooo, I think John made them a while ago…I’ll send you the link to them.” You finally obtain the link and you look at the personas. You can almost see the layer of virtual dust accumulating over the surface, and some virtual cobwebs starting to form in the corners. These were so hidden, it is pretty clear no one has used them. You slack your coworker:

You: Hey, thanks for these. Could you tell me John’s last name? I would love to set up a meeting with him to discuss these.

Your coworker: Oh, John left the company a while back.

Essentially, these personas, created by (poor) John have simply been sitting here gathering dust, which is the killer of all things actionable and productive.

Maybe there is another way to prevent this from happening. We brainstormed a few different ideas:

- Expiration dates. What if outputs had expiration dates, best until 6 months from creation. That way, people are forced to look at the outputs, at least, every six months, in order to evaluate how (and if) they are working. This also helps respond to changes in the product, market and company

- A three month retrospective. If no one has used the outputs to make any sort of product decisions or improvements, they need to be seriously reevaluated. If the team isn’t using them, they are officially not actionable, which renders them rather useless. By doing a retrospective every three months, we can keep outputs alive and relevant

- The Null Hypothesis. This one is fascinating to me. Microsoft works with the null hypothesis concept, they assume things are wrong, until they are proven right. If you create an output assuming it is wrong, you will need to prove it is right, which means you will be constantly looking at and using the outputs in order to validate them

Introducing doubt

All of these concepts boil down to this final idea of doubt. As user researchers, we need to be okay doubting our research, because, we need to tell people it can change: outputs can changes, insights can change (or be wrong), users can change.

Are user researchers the only ones who aren’t allowed to make mistakes or learn from the job?

We generally spend so much time convincing people to see the value of user research, and to buy-in to this still foreign concept of speaking to users. With this, it is terrifying to admit mistakes or to tell people something might change. We believe, when we open up this avenue, we may lose the trust or support we worked so hard to achieve. In fact, it should be the opposite:

We should be able to question our own work and insights

Outputs should be able to change and be iterated on, even when they appear “done”

Users and research should be able to grow through time, and still have a high amount of value

Doubt doesn’t have to be bad, in fact, it can keep things from staying static, and allow them to breath and evolve.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

Defining your User Research philosophy

Why are you a user researcher?

Questioning and exploring your beliefs as a user researcher can be extremely important, as it can help you develop your philosophy of user research. This helps you understand and articulate what you interpret are the best approaches to user research, and why you are a user researcher. Examining your thoughts behind the research process, such as methodologies, recruiting, notetaking, analyzing and sharing, can help you define your own process, and give others a good understanding of how you approach and implement user research into a company. Before you are called for an interview, this statement, along with your résumé, will give your possible future employer a first impression of you. It can also be extremely helpful when trying to build a research framework at a company.

I think, as user researchers, we do a lot of reading and learning; we try to understand the best techniques for the given situations, we discuss different methods and ways of conducting research, we try to list best practices for every aspect of the research process. Bottom line: we ingest a lot of information. What do we do with that information? We try to apply it and put it into practice to see what happens.

As we progress through our careers, I believe we start to shape our own understanding of user research processes, and tend to develop patterns on how we approach problems. We have spent much time piecing together all of this incoming knowledge to inform us, but have we taken time to define our own process, with all its unique twists and turns? Maybe it is time we sit down and think about our philosophy of user research and how we got there.

Questions to help define your philosophy of user research

- How do I think? What is my set of beliefs based on: past experience, personal ideals, surrounding knowledge, schooling, classical ideas?

- What is the purpose or value of user research?

- What is my role as a user researcher?

- How should I evangelize and share user research? Do I transmit information to teams or take a facilitator approach?

- What is the role of the company in user research? How can each department respond or help me with conducting, analyzing and sharing user research?

- What are my goals as a user researcher, both inside and outside of a company? How do I contribute to the user research community?

- Why am I a user researcher?

I definitely have my own framework and process that I bring to each research project, my own way of thinking, however, it was only after being in the field for over 5 years that I actually sat down to define my own user research philosophy. And that was just recently. Maybe I am a bit behind the curve, and people do this regularly!

The act of formally sitting down and answering these questions was immensely helpful for me. Not only did it reiterate the fact that it is important for me to understand where my own thoughts, perceptions and biases come from, but also that there are other ways to approach problems outside of mine. Additionally, I can better articulate my beliefs and framework, which help others in understanding where I am coming from and what my process might look like in a given project.

Aside from the user research project, it also helped me in remembering why I became a user researcher and all the things I love about this profession. I restated my goals, which also remind me of my motivations and values. For me, this was an invaluable exercise that helped me redefine my goals, and for the people I work with to better understand who I am as a user researcher.

[embed]https://upscri.be/ux[/embed]

The value of user research

8 Benefits of User Research.

I recently realized I haven’t written an article explicitly stating what the value of user research is. I’ve implied in some articles, but haven’t been straightforward in my approach. As there are many varying opinions on the importance and need for user research I thought, why not throw another article into the mix? Maybe it will be helpful.

I had been interviewing with a company early on in my user researcher career. I had made it past the initial round and was practically oozing with excitement for the next round. I was asked to present a powerpoint case study, which was standard. I had not yet nailed down my exact process, nor was I completely confident in my presentation skills, but I was as ready as I could be. After the presentation, which went fairly well, I was asked, “so, what is the value of user research?”

There were two thoughts that sprang into my mind in that moment:

- Sh*t, I clearly didn’t convey that in my presentation (which ended up being an invaluable learning)

- Uhhh, think, think, say anything intelligent besides, “because you should”

I had no idea what to say. I knew what I wanted to convey, a feeling and reasoning, but I couldn’t form it into words outside of, “what else would you do? How else would you make decisions?” I knew those questions wouldn’t lead me down the right path. I sputtered something like, “it helps you make data-informed decisions that the users will want.”

Not the most eloquent. I’m pretty sure I meant to say data-driven decisions (everyone loves an alliteration), which wasn’t technically what I meant, because I was trying to push my qualitative research skills; not to say qualitative research isn’t data, but they definitely took that as a sign that I love to do quantitative research, and would incorporate quantitative data into my insights. Unfortunately, I wasn’t quite that advanced yet.

Ultimately, I ended up doing fine at that job, and was able to learn a lot, such as accurately defining the value of user research. This certainly came in handy when people have told me user research isn’t important, nor is it necessary to running a successful and profitable business. I’ve read countless articles discrediting this profession, talking about how over the top and inessential research is — basically it is a huge waste of time and money. On the flip side, I have read articles stating how crucial and influential user research can be to a company (luckily, or I’d be out of a job). It can produce a positive snowball effect, that leads to happy customers, happier employees and a larger revenue.

So, here we are, trying to define the value of this skillset, which can be glaringly obvious to those who do it regularly. My list of values continues to evolve and shift as the profession grows and changes, but I wanted to list them, and also understand what your thoughts are on the value of user research.

8 Benefits of User Research

- To build an empathetic, user-focused company that aligns the product and business strategy with the core needs and goals of users

- To understand how people perform tasks and achieve their goals in order to design an effective and pleasurable UX

- To create a shorter development time upfront, with a clear vision of what you are trying to build